This essay was originally published at Senses of Cinema.

* * *

“WTF is this movie?!”

I scribbled this note midway through I Am Here, Fan Lixin’s trainwreck of a documentary about Super Boy, an American Idol-style talent show that is a ratings sensation in China. I walked out of three feature films at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival, each of which was more competently made than I Am Here, but none was as fascinating. Assembled from one-on-one interviews with the contestants, backstage observations, broadcast footage, and fabricated adventures (the film begins and ends with three of the boys walking through the desert, for some reason), I Am Here was surely edited by a committee whose sole concern was protecting and selling the brand. Each sequence feels focus group tested, as if the entire film were compiled algorithmically based on Youku analytics data. Say what you will about shows like Super Boy, but after two decades, its approach to storytelling and montage has become so refined it’s nothing for the editors at Big Brother and Survivor to introduce and individuate ten characters before the first commercial break. After 88 minutes of I Am Here I knew only Ou Hao (the guy with the circle earrings) and Hua Chenyu (the one with the lenseless black frames). In other words, I Am Here isn’t even good reality TV.

Two days later I saw Pedro Costa’s Horse Money, which proved to be my favourite film of the festival, and by a wide margin. The juxtaposition was instructive. Costa works independently with a miniscule budget and shot Horse Money with a camera that can be had on eBay for $400. (1) After the screening he told the audience, “The problem with digital is you have to do so much more to get something interesting… To get some truth or emotion with light, it’s hard today. It takes more work.” In her festival blurb, TIFF programmer Giovanna Fulvi calls I Am Here a “sharp commentary on the changes occurring in contemporary Chinese culture.” Putting aside for a moment the question of how a film like I Am Here even gets programmed at a festival as prestigious as Toronto, I suppose I would agree with Fulvi that the film is a “sharp commentary” but only in an ironic or extra-textual sense. At the risk of hyperbole, I felt at times during the screening of I Am Here that I was witnessing the death throes of cinema. The pretty vacuousness of its images and its radical incoherence are symptoms of this age, I think. Never has it been easier for us to generate compelling images; never has it been harder to imbue them with meaning. During his Q&A, Costa mocked the Dolby trailer that preceded every film at TIFF, calling it “fascism”. I wish he’d seen I Am Here.

Dana Burman Duff’s Catalogue, which screened in the Wavelengths experimental shorts program, addresses this image problem head-on. Shot in black and white and on 16mm, the film at first appears to be a study of domestic space along the lines of Jim Jennings’s Close Quarters (2004), with long static shots of silk curtains, jute rugs, and high-dollar linens. After a few minutes, however, Duff reveals her game: there at the top of an image are the words “Velvet Drapery Collection”; later, two pillows are tagged with product descriptions. Catalogue is old-fashioned in the sense that its central questions are nearly a century old. Where are the lines separating commercial work (home décor magazines) from “high” art (avant-garde film programs)? What cultural and economic forces determine those lines? And to what extent must an artist intervene in the manipulation of found material in order to claim ownership of the new work? (Duff crops and reframes the catalogue pages, her decoupage pops, and the vibrating gears of her 16mm camera bring a semblance of life and motion to the sterile photos.) But Catalogue is timely as well, as it reminds us not only that we’re inundated constantly by sponsored images, but that so many of them are so damn beautiful. Just look at the light in those photos the next time you’re solicited by Pottery Barn.

“My friends who don’t know a thing about cameras or photography regularly post interesting pics on Instagram,” another filmmaker from the Wavelengths shorts program told me. The breakneck evolution of smartphones, consumer-grade digital SLRs, and photo editing apps, combined with Pinterest and other curating-for-the-masses platforms, have enabled users – and I use that word deliberately – to make a pastime of cultivating their visual taste. The average Instagram user might not know terms like shallow focus, tilt-shift, or Kodachrome but he or she knows which filter will produce the most likes. It’s a learned aesthetic calculation. By the same token, I Am Here includes a few moments of striking imagery, especially in the on-the-road sequences, and I suspect that fans of Super Boy have already begun grabbing sequences from the film and posting (or Weibo’ing or Weixin’ing or QQ’ing) edited stills, GIFs and video snippets, finding new contexts for the images and creating new juxtapositions of their own. That I Am Here is a jumbled disaster of a narrative feature is, in many respects, beside the point. A feature film of this sort is just one more content delivery system, and one that can now be marketed with the TIFF “Official Selection” laurel icon.

Which makes a film like Horse Money all the more remarkable. Costa’s latest collaboration with a community of Cape Verdean immigrants in Lisbon opens with a silent montage of still photos by Jacob Riis, a muckraking journalist and social reformer who documented the lives of the working poor in turn-of-the-century New York City. I learned Riis’s name and the subject of the photos only after the screening; they’re presented in the film without context or explanation. I had assumed the images were dusty remnants of Portugal’s past, as if Costa were only making the (familiar) point that historical progress is slow and tragic, that our institutions and economic systems continue to fail the same people in the same ways. However, the montage also recalls, formally, the opening of Costa’s second feature, Casa de Lava (1994), which introduces the topography and people of Cape Verde by cutting together footage of volcanoes with portraits of Cape Verdean women. Costa scores Casa de Lava‘s opening montage with a Paul Hindemith viola sonata, self-consciously announcing his position as an outsider (this is the music of cultured Europe rather than post-colonial Africa) and aligning himself artistically with the modernists. The Riis photos are, likewise, a kind of declaration of principles. Costa is himself something of a muckraker, and the images in Horse Money are similarly sublime, haunted and material.

Costa cuts from the last Riis photo – an image of a cramped alleyway with eight people staring back toward the camera – to a full-colour shot of a painting of a young black man, which creates the effect of an eyeline match. Horse Money is very much a film out of time. To say that the painting acts as a transition from past to present wouldn’t be quite right, as the first person we see, Ventura, is himself caught in a liminal space. Now in his early 60s, he seems to exist simultaneously in the present moment, in 1974 when he was nineteen years old and caught up in Portugal’s revolution, and in all points in between. Since we last saw Ventura in Colossal Youth (2006) he’s developed a tremor in his hands: “I know a bunch of hospitals,” he tells a doctor before rattling off the names of several. The stark white walls of the new housing development in Colossal Youth have been replaced here by a different bureaucratic dystopia, the indistinguishable lobbies, cafeterias, elevators and hallways of our modern healthcare facilities. On those rare occasions when Ventura does step out into the world, it’s an equally strange and symbolic space, littered with monuments, faceless military forces, and rubble. “You’re on the road to perdition,” a woman tells him.

Aside from a brief appearance by Lento, the friend tasked with memorising Ventura’s letter in Colossal Youth, none of the other major characters from Costa’s previous Fontainhas films feature in Horse Money. Instead, he introduces Vitalina, a woman in her early 50s who has recently flown from Cape Verde to Lisbon to bury her husband. She speaks in a raspy whisper and her face is, for now, incapable of expressing much beyond grief and exhaustion. Costa’s style has evolved steadily through the years, and the move toward Cubist-like compositions in Colossal Youth (the signature shot of Ventura dwarfed by the angular towers, for example) now predominates, culminating in a remarkable close up of Ventura’s and Vitalina’s faces in profile. (2) They talk about their loves and losses in intimate detail. “Did you get Zulmira a full wedding dress?” she asks him, tears in her eyes. “Did you buy her undergarments? Headpiece and shoes?” When the voice of Zulmira, Ventura’s long-lost wife, comforts him later in the film, Horse Money fully reveals itself as a Gothic melodrama – and a deeply stirring one at that.

Just Shy of Greatness

That TIFF might be confronting some image problems of its own was apparent from their new tagline, “This is your festival”, which reads as a direct response to the annual stream of editorials that decry TIFF’s betrayal of its original position as “the people’s fest” thanks to rising ticket prices and policy changes that put a heavier premium on gala screenings. As a goodwill gesture, TIFF and the city of Toronto shut down five blocks of King Street during the opening weekend, creating a pedestrian-friendly refuge in what has become, since the unveiling of the TIFF BellLightbox four years ago, the most congested area of the festival. What I found even more interesting, though – and I say this as a communications professional in the non-profit world – is how TIFF’s marketing efforts this year shifted emphasis to the organisation’s status as a year-round arts charity. It’s a difficult message to deliver amidst the marketing noise of the festival itself, and when I heard people discussing it at all their comments were predictably cynical. I admire the effort, though, and thought it was well executed. I suspect it will change the conversation about TIFF ever so slightly; more importantly (for TIFF’s board of directors, at least), it will affect perception among the donor class who attend a few festival screenings each year and can afford to make transformational gifts. If those donations help sustain the TIFF Cinematheque eleven months out of the year, then it’s a small win for cinema culture, cynicism be damned.

Festival politics aside, “witnessing the death throes of cinema” is hardly the experience I was anticipating when I booked my eleventh consecutive trip to Toronto. While I Am Here was certainly the only film that turned my thoughts apocalyptic, and while the best films I saw were indeed exceptional, the lineup as a whole was among the least satisfying of the past decade. Given the size of TIFF’s program (284 features, 104 shorts), generalisations like mine should be taken with whole handfuls of salt, but more often this year than in any I can remember, the go-to conversation starter at TIFF – “Seen anything good?” – was greeted with, “Good, yeah, but not great.” And that sentiment seemed to be shared across the broad spectrum of programs, from the avant-garde to the mainstream. While I tend to avoid higher-profile films, knowing they will eventually receive wide distribution, I usually return home from Toronto with a good sense of which films will soon be getting an Oscars push. The buzz for 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013), Silver Linings Playbook (David O. Russell, 2012), and The King’s Speech (Tom Hooper, 2010), for example, was unavoidable, just as TIFF always hopes. This year, when The Imitation Game (Morten Tyldum) won the People’s Choice Award, I had only a vague sense that it was one of those Benedict Cumberbatch movies.

Like many North American critics, I visit Toronto, in part, to catch up on titles that premiered at Cannes, a tactic that TIFF is now actively discouraging by front-loading the press schedule. (During the morning slot of the first day, seven films I wanted to see screened simultaneously.) My general disappointment with this year’s lineup owes something, I’m sure, to the unusually high number of well-reviewed films that played in Toronto but that I wasn’t able to see, including David Cronenberg’s Map to the Stars, Xavier Dolan’s Mommy, Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner, Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu, Andrey Zvyagintsev‘s Leviathan, Pascale Ferran’s Bird People, and Sergei Loznitsa’s Maidan. In some instances, the Cannes holdovers I did manage to schedule only added to my disappointment – not because they were bad, necessarily, but because they fell so far short of my expectations. Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Winter Sleep is a major step back from Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011), I think. A too-long film buoyed by a few very good scenes, Winter Sleep is essentially a Woody Allen movie (a portrait of the artist as conflicted, self-absorbed, aging intellectual) with too few jokes. Ruben Östlund’s Force Majeure is also too long, but it’s bigger fault is that it borrows the central premise of Julia Loktev’s far superior The Loneliest Planet (2011) and then turns that film’s greatest strength – subtext expressed through ambiguous gestures – into pages and pages of festival-friendly, on-the-nose text. At least it’s funny.

Most of the fall premieres I saw at TIFF also landed in the good-but-not-great camp. The latest in his on-going Shakespeare project, Matías Piñeiro’s The Princess of France is a loose translation of Love’s Labour’s Lost that focuses all of the play’s romantic intrigues on Victor (Julian Larquier Tellarini), a young stage director who returns to Buenos Aires after a trip abroad and immediately becomes entangled (or re-entangled, or potentially entangled) with each of the five actresses in his troupe. The film opens with a stunning, high-angle shot of an amateur football match that, had it been screened as a stand-alone short film, would have been a highlight of the fest. The rest of The Princess of France, however, fails to maintain the same formal and aesthetic heights. Piñeiro’s own troupe of actresses are never less than a pleasure to watch – after seeing her here, in Piñeiro’s Viola (2012), and in Santiago Mitre’s The Student (2011), I now look forward especially to every new appearance by Romina Paula – but Piñeiro is at his best when he’s observing groups of people, their faces falling into and out of frame at various depths of field. He finds a rare and distinct magic in those moments. His voice is less clear in more traditional dramatic stagings, of which The Princess of France contains many, and Tellarini lacks the screen presence necessary to carry so much narrative weight. The various competing relationships lose their tension as a result, and the film turns a bit flat.

Viola includes a wonderful scene in which two actresses are rehearsing an exchange from Twelfth Night, and as they repeat their lines again and again, the performed seduction gradually becomes real. At least among the two Piñeiro films I’ve seen, it’s the most effective use of repetition as a formal device, which seems to be an ongoing concern for him. The Princess of France restages on several occasions a scene in which Victor picks up his backpack from under a tree, and with each recurrence he’s pitted against another of the women in his life. In that sense, The Princess of France could very well be a Hong Sang-soo film. Hong’s latest, Hill of Freedom, concerns a Japanese man named Mori (Ryô Kase), who returns to South Korea in hopes of reconciling with a former love, Kwon (Seo Young-hwa). In the film’s opening moments, Kwon drops a bundle of letters sent by Mori, which is Hong’s narrative justification for jumbling the chronology of events and exploring, once again, the fickleness of memory, perception and affection. Hill of Freedom is charming and laugh-out-loud funny, but at just barely an hour it’s something of a trifle.

Like his previous film, Berberian Sound Studio (2012), Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy, which world-premiered at TIFF to mostly rave reviews, is an impressive display of style in service of a clever short-film idea stretched to feature length. Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen) and Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna) are a couple who enjoy a little S&M, one of them more enthusiastically than the other, and it’s that imbalance that makes the scenario so interesting. Cynthia, the would-be dominatrix, punishes Evelyn for her mistakes by locking her in a trunk or pissing in her mouth, but her every action is scripted, quite literally, by Evelyn. As we watch them perform their duties repeatedly throughout the film (to say The Duke of Burgundy has a cyclical structure would be an understatement), it all begins to seem routine – boring, even.

That’s the point, of course. Strickland is interested in how long-term relationships become defined by everyday habits, and The Duke of Burgundy is at its best when it foregrounds those expressions of generosity, intimacy and tenderness that make love a worthy effort. More often, however, the film is a catalogue of sensations. Strickland indulges his every aesthetic fetish – ‘70s Euro softcore, Bunuelian absurdism, Stan Brakhage! – and has great fun doing so, but watching The Duke of Burgundy is a bit like link-hopping on YouTube. As with I Am Here, the film’s best moments are, in fact, the simplest to reproduce. For example, a striking, golden image of a hand clutching bed sheets, accompanied by a loud, pulsing soundtrack is arresting but ephemeral, like a run of the mill music video. (I had similar reservations about Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin last year. That both films indulge male fantasies adds to my concerns about the directors’ reliance on sensation, but that’s a subject for a longer essay.) The last 30 minutes of The Duke of Burgundy are a patchwork of such scenes with sparse connective tissue. Strickland manufactures transitions out of musical montages, padding out the film with recycled images and ideas. Eventually, his brand of pastiche also begins to seem routine – boring, even.

Something in the Atmosphere

As usual, one of the highlights of TIFF was the annual four-night gathering at Jackman Hall for the Wavelengths shorts programs. Interestingly, it’s there, a few blocks north of the main hub of activity, amongst the relatively close-knit community of avant-garde enthusiasts, that TIFF still feels most like “the people’s fest”. If the films on average weren’t as strong as in recent years, there were several notable high points, especially in program two, “Something in the Atmosphere”. Borrowing its name from Mike Stoltz’s nostalgic 16mm portrait of Florida’s mythic-turned-kitschy “Space Coast”, the program was cohesive despite a lack of any easily identifiable unifying principles, either formally or thematically. Short film programming is such a tricky business. (3) Often, as in this case, I think the best sequences of films can be justified simply as an instantiation of the programmer’s taste. In her notes, Andréa Picard describes the tone of these seven films as “slightly amiss, uncomfortable, and, in some cases, surprisingly alluring,” which seems about right to me. Along with Something in the Atmosphere and Catalogue, the program also included Antoinette Zwirchmayr’s The pimp and his trophies, a 35mm memoir about her grandfather’s brothel, which brought to mind a slightly more sympathetic version of Heinz Emigholz’s grotesque D’Annunzios Höhle (2005); Relief, Calum Walter’s latest mash up of analogue printing, digital imaging and frame-by-frame animation (Walter’s use here of images from a car accident grounds thematically the technique in ways that are lacking in his earlier film, Experiments in Buoyancy [2013]); and Beep, Kim Kyung-man’s Brechtian interruption of North Korean propaganda films. The remaining two, Blake Williams’s Red Capriccio and Jean-Paul Kelly’s The Innocents, are especially deserving of attention.

At a festival starved for new images, it was a pleasure to encounter three filmmakers of different generations, including Williams, who wrestled playfully with the mechanics and possibilities of 3D. (4) Earlier this year, the Edinburgh International Film Festival premiered digital restorations of Canadian animator Norman McLaren’s stereoscopic films, two of which also screened in TIFF’s Short Cuts Canada program: O Canada (1951, directed by Evelyn Lambart using a technique invented by McLaren in 1937) and Around is Around (1951). In the latter, which was the first-ever stereoscopic animation, McLaren used a cathode-ray oscilloscope to generate wave forms and graphic, geometric patterns. I won’t pretend to know exactly how Around is Around was made, but it was, quite simply, the most delightful ten minutes of the festival. Also delightful – and confounding and funny and unexpectedly moving – was Jean-Luc Godard’s Goodbye to Language, about which I can only say, after a single viewing, that it is filled with nothing but new images. (The recurring shot of fingers wrapped around the rails of a gate is uncanny in exactly the way I’ve always wanted 3D to be uncanny but never is.) Even relative to Godard’s post-Histoire(s) work, Goodbye to Language is uncommonly dense. I hope to write about it some day, but only after doing the hard work of excavating its stacked layers of images, sounds, dialogue, quotations, music and stereoscopic effects.

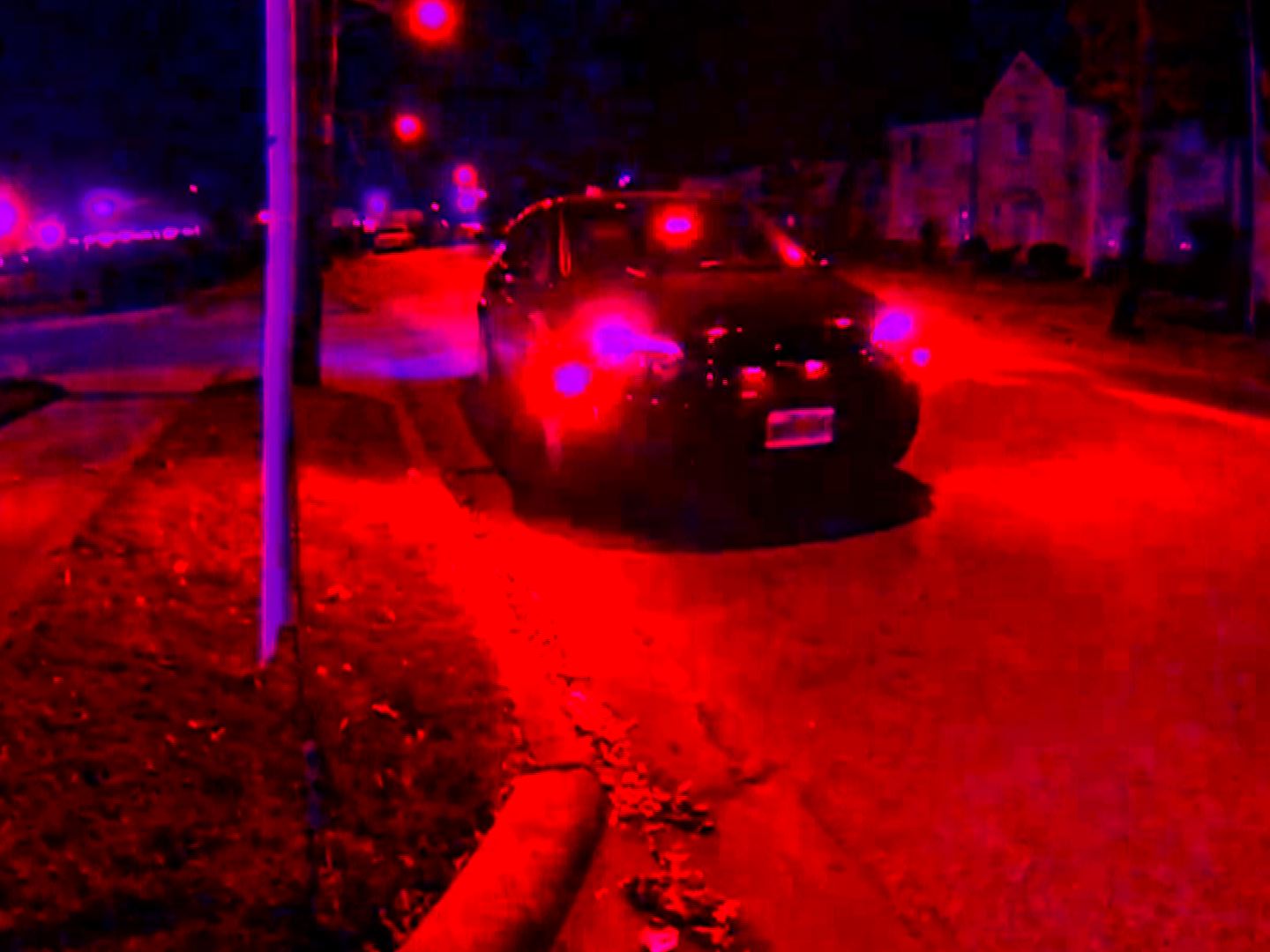

In his artist’s statement, Williams explains that his latest video borrows its structure from Stravinsky’s and Tchaikovsky’s capriccios, which are “playfully shaped from clashing staccatos and glissandos, and prone to sudden, dramatic tonal shifts.” It’s a clever move because it frees Williams to experiment within loose but essential formal constraints. Red Capriccio races through three movements in barely six-and-a-half minutes, and it’s the juxtapositions between them that make the larger piece so compelling. The first and longest section is constructed from handheld shots of an unmarked police cruiser (a Chevy Caprice, natch) that is parked on an empty street at night with its lights flashing. Playing variations on this theme, Williams cycles several times through a sequence of images of the car, modifying shot lengths and anaglyph effects with each return. Around the three-minute mark, he cuts to a montage of footage shot by travelers as they speed down the mostly vacant Turcot Interchange, a labyrinthine network of highway overpasses that first opened to traffic in anticipation of the 1967 Montreal Expo. The final and most mysterious section is a series of three shots: an image of a small suburban house that is illuminated first by a spotlight on the right and then on the left; a demonstration of a lighting rig inside a small and empty disco; and, finally, a sports car spinning recklessly in tight circles.

Red Capriccio, like most of Williams’s recent work, is assembled from material that he has scavenged from the Internet and then converted to anaglyph 3D. Many a Swan, which screened at Wavelengths in 2012, treats the found, two-dimensional images as pieces of paper, folding and bending them like origami. In Baby Blue (2013), he experiments – in the true sense of the word – with parallax, exploring the 3D effects that result when objects move horizontally through the frame at various speeds and at various depths of field. Red Capriccio continues this inquiry into the fundamental components of anaglyph 3D by focusing on blue-red separation. The flashing lights of the police car, for example, are a keen and quintessential demonstration of the mechanics of anaglyph. Williams’s interest in form, however, serves only as a starting point for these videos. He is a structuralist, but only in the sense that the structure prescribes certain boundaries within which his other ideas are confined. (The Internet is an inexhaustible source of material after all.) In other words, while the 3D effects in his recent videos are essential and compelling, they don’t alone determine the ultimate success or value of each individual work.

To be frank, Williams’s experiments with anaglyph don’t interest me nearly as much as his montage and his taste. Before rewatching it recently, I had only vague memories of Many a Swan, with the exception of a moment near the end when Williams cuts from a noisy, syncopated, and rapid-fire sequence of images to a silent, slow-motion shot of origami master Akira Yoshizawa folding a swan. It’s the video’s big reveal, as it explains the title and contextualises many of the work’s larger ideas, but that cut – the way it made me catch my breath and shift my perspective – is where Williams’s true talents lie. Red Capriccio is the best of his 3D videos because it contains the highest concentration of those moments. By the same token, Baby Blue is the weakest, I think, because the formal ideas are more interesting than the montage. Red Capriccio‘sfootage of the Turcot Interchange is alien and beautiful, recalling the 18th– and 19th-century paintings of “fantastical and sublime” architecture that inspired Williams. More impressive, the two-minute sequence builds imperceptibly (on a first viewing) toward an astonishing cut to black. Having now watched Red Capriccio a half-dozen times, I find myself anxiously anticipating that cut because the leap from that sequence to the final section is both logic-defying and ineffable. It makes me smile like an idiot. That the last shot of Red Capriccio favourably recalls Denis Lavant’s dance at the end of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999) is, perhaps, the best compliment I can give Williams.

The first section of Jean-Paul Kelly’s three-part film, The Innocents, is a nearly seven-minute shot of two hands methodically placing and then removing dozens of printed photos, each of which has been pierced in one or more spots. The cutout holes vary in size and location, and each has a small, conspicuous ring of colour around it. The photos also vary greatly – in style, source and content – but gradually a few themes emerge: sites of violence and decay (an abandoned home, soldiers, bombed out buildings, a bullet-riddled body), homosexuality (gay porn, intimate selfies, protests for marriage equality) and media representations that conflate the two (Anderson Cooper, political hearings, Chelsea Manning, In Cold Blood, Glenn Greenwald). The middle section, shot on 16mm, is a silent restaging of snippets from With Love from Truman (1966), Albert and David Maysles’ documentary interview with Truman Capote. In Kelly’s version, a tattooed, muscular man in a white tank top and with a plastic bag fitted loosely over his head imitates Capote’s gestures, a marker in one hand, a highball in the other, while Capote’s bon-mots on form and style display below as subtitles. The final two minutes of The Innocents recall the opening section with a series of grainy, scratched 16mm images of coloured circles against a white background.

Kelly offers a clue to his strategy with the first image in the opening series, David Boudinet’s “Polaroid” (1979). Boudinet’s photo of blue, sheer curtains in near-darkness also appears on the title page of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, in which Barthes attempts to better understand and explain his own subjective, sentimental experience of photography. In it he proposes a useful distinction between studium – the culturally-learned, political and intended content of an image – and punctum, which is a “sting, spack, cut, little hole… that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” Kelly’s printout of “Polaroid” has been pierced midway down the image, just to the right of centre, which excises a small section of the photo where the curtains are slightly torn. In this opening series, then, Kelly has literalized punctum, systematically removing from each photograph that mysterious thing that “fantastically ‘brings out’” the true nature of the image.

Truman Capote is a complicated figure, and Kelly’s film is in part a critique of the man, both as an artist and gay icon. The Innocents foregrounds the ease with which Capote justifies his treatment of violence in In Cold Blood (“I chose [the brutal murder of a family] because it happened to accommodate an aesthetic theory of mine”) and distances himself from his own moral responsibility, as if the words on his page materialised magically (“style… comes naturally, like the colour of your eyes”). But Kelly’s larger concern is the systematic and sensational representation of the gay male body as something dangerous and pathological – a form of political exploitation that can be traced back well beyond Capote’s “poetic” depiction of murderers Dick Hickock and Perry Smith. Like Camera Lucida, The Innocents speaks in a subjective voice – presumably, these are photos that bruise and sting Kelly personally – which makes the final section all the more affecting. Barthes wrote, somewhat controversially, “in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes” (p. 53). This characteristic distinguishes photography from cinema, he argues. The closing images of The Innocents are a counter argument to Barthes, I think, as they force viewers to experience retroactively the disorienting, “ill-bred,” and “lightning-like” chill of punctum.

Discoveries

One pleasure of attending a festival as large as TIFF is stumbling upon filmmakers like Israel Cárdenas and Laura Amelia Guzmán, the husband and wife who co-wrote and co-directed Sand Dollars (Dólares de Arena). Set in a beachside town in Guzmán’s native Dominican Republic, the film concerns a love triangle between twenty-something Noelí (Yanet Mojica), her unemployed boyfriend (Ricardo Ariel Toribio) and Anne (Geraldine Chaplin), an aged European ex-pat with whom Noelí has had a years-long romantic and financial relationship. I say “pleasure” because from the film’s opening shot, a beguiling close up of an old man singing in a nightclub, I trusted Cárdenas and Guzmán, trusted their taste and perspective. The first cut, to men playing Bocci on the beach, establishes with remarkable efficiency both the style of the film and the rules of the world in which these characters operate. Sand Dollars is leisurely paced, and Cárdenas and Guzmán’s camera is attentive to bodies and gestures, to the routines and transactions of daily life in this economically- and racially-divided paradise.

Cárdenas and Guzmán introduce Anna by first leading viewers through the resort where she and other wealthy ex-pats bide their time. Noelí wanders in with an easy familiarity, changes into a bikini, and then finds Anna on the beach, where they enjoy a swim together. When they return to the room, the arc of the story is already written on Anna’s face. Chaplin’s wistful eyes and fragile expression, hallmarks throughout her long career, leave little doubt that every moment of joy she experiences will be fleeting. Such is the bargain she’s made, exchanging money for time, affection and a fool’s hope in love. Sand Dollars sidesteps the major traps of films like this: owing to Cárdenas and Guzmán’s observational style, the characters come to embody certain tendencies of their post-colonial condition without ever becoming cogs in an allegorical machine. If the film occasionally feels too familiar – Sand Dollars fits comfortably into the “post-Dardennes international film festival film” genre – that’s a small complaint. I’m eager to see what Cárdenas and Guzmán do next.

In many respects, Stéphane Lafleur’s Tu dors Nicole is a film we’ve all seen dozens of times before. Nicole (Julianne Côté) is one more descendent of The Graduate‘s Ben Braddock, a suburban 20-something drifting aimlessly and reluctantly toward adulthood. When we first meet her, Nicole is getting dressed and attempting to sneak out after a hookup. “Will I see you again?” the guy asks. “What for?” she answers. It’s a typical response for Nicole, who is reticent, passive-aggressive and profoundly melancholy.The film follows her for a few days one summer when her parents are away on vacation. She’s living at home and working at a thrift store, where she sorts clothes with the same bored detachment that characterises so much of her life. During the day, Nicole hangs out with her best friend, Véronique (Catherine St-Laurent), or listens to her older brother rehearse with his band. A chronic insomniac, she spends her nights wandering through the neighbourhood, peering curiously into the lonely lives of the strangers on her street. If Tu dors Nicole were prose, it would be in the spare, wistful style of Raymond Carver, which is what makes the film such a pleasant surprise.

Tu dors Nicole takes its title from a line in the penultimate scene, when Nicole is woken up by the mother of a young boy she’s babysitting. “You’re asleep, Nicole,” she whispers – the most literal wake-up call in the history of coming-of-age movies. It’s a hard-earned line, though. Lafleur’s style recalls a number of filmmakers – Wes Anderson’s perpendicular camera angles and balanced compositions, Hal Ashby’s long-distance cutaways, Jim Jarmusch’s sound designs – but it avoids being derivative by virtue of the film’s subjectivity, which is aligned intimately with the main character. Tu dors Nicole is about the gradual build-up and explosive release of pressure in the life of a young woman, and much to his credit Lafleur builds that same tension into individual scenes and into the larger narrative. All of Nicole’s repressed pain and desire are manifest in the world around her – in the jammed bicycle lock she shakes violently while talking to Véronique, in the music and conversation that seeps through the walls when she tries to seduce the band’s drummer, in the loud lawnmowers and electric fans that seem to pollute every moment of potential quiet. The film’s turn to magical realism in the final image, then, is less surprising than inevitable and necessary.

Soon-Mi Yoo’s Songs from the North, which premiered at Locarno and screened in TIFF’s Wavelengths features program, opens with a striking piece of found footage of highwire acrobats. The camera is positioned at a great distance, as if from the far side of a stadium, which turns the performers into small and illuminated figures against a deep black backdrop. An acrobat falls, there’s a gasp from the audience, and then a jarring cut to radically different found footage, this time from, presumably, a 1980s-era propaganda film about North Korea’s rocketry program. That cut, and the logical and aesthetic juxtapositions it generates, is a worthy introduction to Songs from the North, which swings constantly throughout its relatively brief running time (72 minutes) between numerous modes of discourse: a talking head interview, text inserts, original documentary material, and a broad range of found footage, including North Korean fiction films and television broadcasts.

In her interview with Adam Cook, Yoo classifies Songs from the North as a “poetic essay” and describes the challenge of taking on a subject as complex as North Korea: “It is always tricky, when dealing with such loaded historical and political issues, to know exactly how much information you should provide without turning your film into a lecture.” Her solution is to speak very little in the first person: the text inserts are seldom more than a sentence and we hear her voice only occasionally in the documentary sequences. She presents her argument, instead, through the curating of images and sounds and, most importantly, through her montage. Ideally, in a poetic essay such as this each cut functions as a koan, creating a dissonance that transcends logic while still leading the attentive viewer toward a (relatively) specific end. That Yoo scarcely achieves that ideal is, perhaps, too easy a criticism. Indeed, I found myself falling into the film’s rhythms and experiencing the collective weight of its images just as Songs from the North ended. But the film is both too much and too little; there are too many voices (I understand why Yoo includes the interview with her father but it breaks the film’s form) and too few images (I can’t not compare the experience of watching this film to Andrei Ujica’s three-hour The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu [2010]).