This interview was originally published at Mubi.

* * *

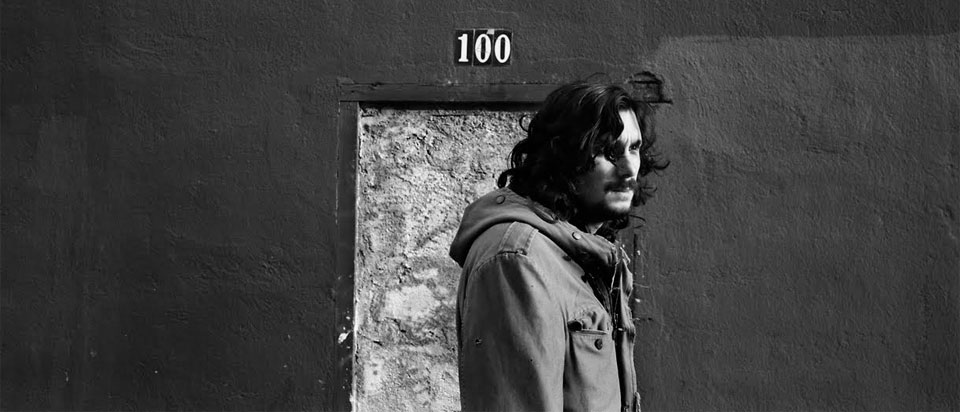

“I am not an ideologue,” José Luis Guerín says matter-of-factly. “I need characters.” Judging by the lukewarm response that has greeted his latest film, Guest, it’s a dicey stance for a director of art house cinema to take these days. Early reviewers have praised Guerín’s images but questioned the structure of the film, which often finds him wandering through Third World cities and inviting conversations about hot-button topics like immigration, colonialism, and religion. That he does so without any pretense of deep sociopolitical analysis makes Guest something of an anachronism: it’s a politically-interested film in an observational mode, more humble and curious than didactic.

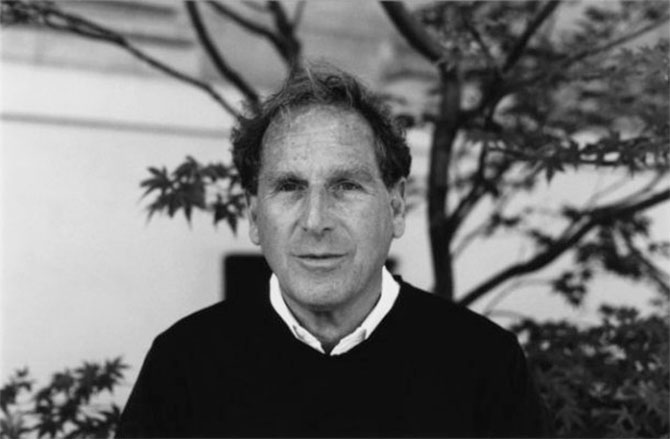

In 2006, after premiering his previous film, In the City of Sylvia, Guerín decided to spend a year traveling the world by accepting every festival invitation he was offered. He carried a consumer-grade DV camera with him wherever he went and very gradually built a “recording journal” of his travels: Venice, New York, Bogota, Havana, Seoul, São Paulo, Cali, Paris, Lisbon, Macao, Jerusalem. (Fans of Sylvia will recognize the return of one of its signature shots: a close-up of journal pages blowing in the breeze.) Along the way, he encountered a few familiar faces—Chantal Akerman and Jonas Mekas make memorable appearances in Guest—but spent the bulk of his time in public spaces, talking to locals, visiting their homes, trying, as he told me, to be a traveler rather than a tourist.

By his own admission, Guerín approached this film with few preconceptions and was content, instead, to discover leitmotifs and organizing principles in the editing room. What emerged in the process are general themes: homelessness (both literal and metaphoric), mythmaking, melancholy/nostalgia, and alienation—specifically, the alienating effect of the cinema. Guerín aspires with Guest and with his work, generally, to counteract this tendency, to make the workaday routines of life new again. That’s one reason for Guests’s black-and-white photography. “Color is not neutral,” he said after the first screening in Toronto. “I wanted the film to be a series of portraits.” It’s Guerín’s Modernist bent, I think—his commitment to form—that gives Guest its heft.

Guerín’s English is slightly better than my Spanish and French, so we spoke slowly and laughed a good bit. With his encouragement, I’ve expanded some of his answers without, I hope, losing his cadence.

* * *

HUGHES: In the Cuba section, there’s a homeless man who’s very upset about the homeless problem, and he says that all the Cuban government cares about is tourism. The word “tourism” can have negative connotations, while “guest” is more positive.

GUERÍN: Well, this was my situation. For that year, I was just a guest. I went where I was invited. This was the pact I made. Each time I arrived at a festival, I would see on this small table beside my bed my credentials with my photo and the word “guest.” A guest is nothing—maybe it’s positive, maybe it’s negative. You can be a guest traveler or a guest tourist. Maybe I’m also a tourist, but I chose for my movie to try to be a traveler—to concentrate on faces, on humans, on characters.

The great benefit of traveling is that it gives you the capacity to recreate your own street, your own space, your own city—to rediscover the quotidian. Ordinary life! This is the essential material of cinema. Usually, you walk down the same street each day; eventually you cannot see your own city. But when you travel and walk an unfamiliar road, there are constant surprises and small discoveries. These discoveries exist on your own street as well, though. For a filmmaker, this change of perspective is important because it’s the opposite of exoticism. A tourist is looking only for the exotic. A traveler is looking for something singular that is also recognizable from their own life.

HUGHES: You’ve cited the Lumière Brothers and Italian Neo-Realism as this film’s heritage. Are Chris Marker and Agnès Varda also part of your heritage?

GUERÍN: Of course. Chris Marker is very important to me, but we are very different. Marker is a worker of words. His voice-overs confront the image in a dialectic. It’s his own genre. He’s a poet and an ideologue. I am not an ideologue. Marker is concerned primarily with ideas; I need characters.

In this sense, my heritage is closer to King Vidor and the Italian Neo-Realists. But like all filmmakers, or like anyone who loves the cinema, in my everyday life and when I travel, there is a constant dialog going on between my imagination, which has been formed by books and movies, and life. This is a great function of art—to help you rediscover life. Too often it’s the opposite: cinema creates alienation.

For example, when I first arrived in New York, I realized I could not make an image of the city. I was already carrying an accumulation of cinematic images and imaginations. I didn’t see New York; I saw the image of New York. This is why I included the scene of Portrait of Jennie. [In Guest, Guerín watches William Dieterle’s 1948 film in his New York hotel room.]

HUGHES: You’re obviously not an ideologue like Marker, but you are a Spaniard who is traveling through the Spanish-speaking Third World and choosing to take your camera into public spaces and into homes. So the film might not be arguing from a particular ideology, but it’s still explicitly political.

GUERÍN: Colonialism, you mean? Of course. Yes, of course. What most interests me is the legacy of Spain on the imagination of these countries. “Print the legend!” {laughs} The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance! “Print the legend.” There are so many ideas and stories about the influence of Spanish people. The past, finally, is a legend.

HUGHES: I love the man who points to the statue of Simón Bolívar and says, “He’s Roman from the neck down.”

GUERÍN: Yeah, yeah, yeah! And he even remembers the size of Bolívar’s shoes! {laughs} This is important, though, because it points to the idea of a popular culture [the unique culture of a particular people], which is disappearing in Europe. It’s finished in Europe. All of these incredible people in Latin America evoke the Europe of my childhood. In them you see the characters of Rossellini and De Sica, the films of the ’40s. Or the American Great Depression. You see people from Vidor, William Wellman, and John Ford.

It’s a curious thing. I know the good Cuban cinema of the ’60s but nothing of, say, classic Chilean film. But these European and American films help me to see the people of Latin America. Do you remember this film, Human Remains, with Spencer Tracy and directed by Frank Borzage? [Human Remains is a direct translation of the Spanish title given to Man’s Castle (1933).]

HUGHES: No, I don’t know that one.

GUERÍN: Oh, it’s a very good movie. Spencer Tracy plays a man who is out of work and walks around wearing one of those signs [a sandwich board]. You can see that in Brazil, in São Paulo—a lot of men out of work and trying to sell gold [jewelry]. It’s too long a story for now {laughs} but this Borzage film is very good, with a social perspective.

HUGHES: I love his silent films. Such beautiful melo…

GUERÍN: Melodramas, yes. {laughs}

HUGHES: One of the leitmotifs running through Guest is the work of daily life. We see women chopping onions, making bread, washing clothes. The struggle is similar from country to country.

GUERÍN: There are different levels of poverty, though. For example, in Bogota, where there are storytellers and poets in the street, this is quite different from the people who have been evacuated from war. In Palestine, a specific political situation has provoked this poverty.

That’s true, though. When I’m looking for a composition, I’m looking for a complimentary relation. For example, the second part of the film focuses mostly on women. And in these women you can see a sequential development. You see a homesick and lonely Philippine immigrant working in Hong Kong, and you see in Columbia a woman who is dreaming of immigrating, maybe to Spain. These are different relations with immigration, but there’s a unity here also.

I’m looking for similar qualities, similar gestures. For example, the women making bread—this is a visual unity across cultures. This is the structure of the movie. It’s this diversity, these fragmentary parts, with a corresponding sense of narrative evolution, sometimes more secret, sometimes more evident.

HUGHES: One visual unity you create is with a particular composition. You shoot the groups of women evangelists in tight closeups with their faces overlapping. It’s the same composition you used at the café and tram depot in In the City of Sylvia.

GUERÍN: It’s like a collage—a lot of faces in profile but, finally, it’s one face. This is a very powerful visual solution discovered by the Renaissance painter Giotto. Two faces: the face of Joachim and the face of Anna, organized as a single head. It’s a very good idea—the repetition and opposition of faces. The visual discourse of In the City of Sylvia is in this image.

HUGHES: Your films make me very conscious of something that is basic and fundamental to the job of a director: choosing where to put the camera and what to point it at. In Guest, Jonas Mekas talks about “chance.”

GUERÍN: Ah, yes, yes. Choice versus chance. Jonas Mekas is the film’s Oracle. I need to explore, every time, this limit between control and chance. This, for me, is the most important aspect of cinema. I think the history of cinema revolves around this idea: How much is control? How much is chance? In the Lumière Brothers? In Jean Renoir? In Hitchcock? In Ford? One function of contemporary cinema is to go further with this conflict.

All of my cinematographic ideas are born in this dialectic. For example, in In the City of Sylvia—and maybe this is naïve and too simple—but I wanted to shoot a fictional movie on a streetcar. I love streetcars in the cinema. Murnau’s Sunrise, for example. I would organize a sequence by writing dialog and working with the actors, but then there would be a confrontation with chance. Absolutely. Chance. I shot on an ordinary tramway. One part of it was for ordinary people, one part was for the shoot. {laughs} I hadn’t the money to take over the entire tramway.

Now, for me it’s a big revelation to see my work in the script and with the actors confronted by this other movie—this real window. You might see one moment of the scripted scene when the tramway stops, or you might get one phrase or one word of the dialog. You might see the actress’s face in darkness or in light. All of these elements change the essence of my mise-en-scene.

One side of this is control, and I love this tradition in the cinema—Murnau, Hitchcock, Ozu, filmmakers who controlled the elements in a studio. But I also love Flaherty and the direct cinema and the Maysles brothers. The tramway is emblematic of my illusion of the cinema. I need to be the first spectator. Cinema is a site of revelation. If I knew everything about my movie while writing the script, I would lose my desire to make it. It should be a revelation.

HUGHES: Those are the most exciting moments in Sylvia—those very brief glimpses of faces in the windows, all of them possible Sylvias. It’s a classic spectator experience. They remind me of Bernstein’s story in Citizen Kane.

GUERÍN: Yes, yes, although that story is even more like the other film, Unas fotos en la ciudad de Sylvia. I remember those moments very well. {smiles}

HUGHES: One last question. The old man in Cuba, “Don Quixote,” you met with him twice? [“Don Quixote” is an aged, homeless Cuban man who still carries his original Communist Party membership card.]

GUERÍN: Yes.

HUGHES: Did you ask him to bring photos the second time?

GUERÍN: No, no, no. He always carries with him all of his objects or belongings. That’s a curious question. These men represent something very human. They’re poor and in a problematic situation. But I see something more in them, something deeply human. Chaplin is maybe the best portrait of the human condition? And in this man I came to see something of the same sense.

Usually, the characters in Guest are people who came to the camera. It’s not me who came looking for them. It’s very curious. They are complicit. They want to speak. They probably need to communicate. They want to make something together. They’ve lost their original land. It’s a sign of the times, the end of rural life—which comes back to that loss of a popular culture. They’re outsiders, between spaces, unable to integrate into city life.

“Don Quixote” remembers all of the people he’s left behind, his lost home, like John Wayne in The Quiet Man. {smiles} There are metaphors in my status as “guest.” I’m very comfortable, bourgeois, but I’m also complicit with them. These are the people I prefer.

HUGHES: He’s very noble, “Don Quixote.”

GUERÍN: Yes, yes, yes. It’s curious. Like many of the men in Guest he carries a memento of a woman. The film is filled with men who are alone and women who are alone. Maybe that’s why they want to talk to the camera. {laughs}

HUGHES: Nostalgia?

GUERÍN: And melancholy.