This interview was originally published at Cinema Scope

* * *

There’s no exact precedent for the long creative collaboration between Tsai Ming-liang and Lee Kang-sheng. In 1991, as the story goes, Tsai stepped out of a screening of a David Lynch movie and spotted Lee sitting on a motorbike outside of an arcade. The director was struggling to cast a television program about troubled teens, so he struck up a conversation with Lee and invited him to audition. During the shoot Tsai became frustrated and began to doubt whether Lee could perform the role, and in the process he discovered that the problem was his own expectations. “I was projecting too many of my own ideas onto Lee’s performance, rather than allowing him to draw upon his own natural way of behaving,” Tsai told Declan McGrath in 2019.

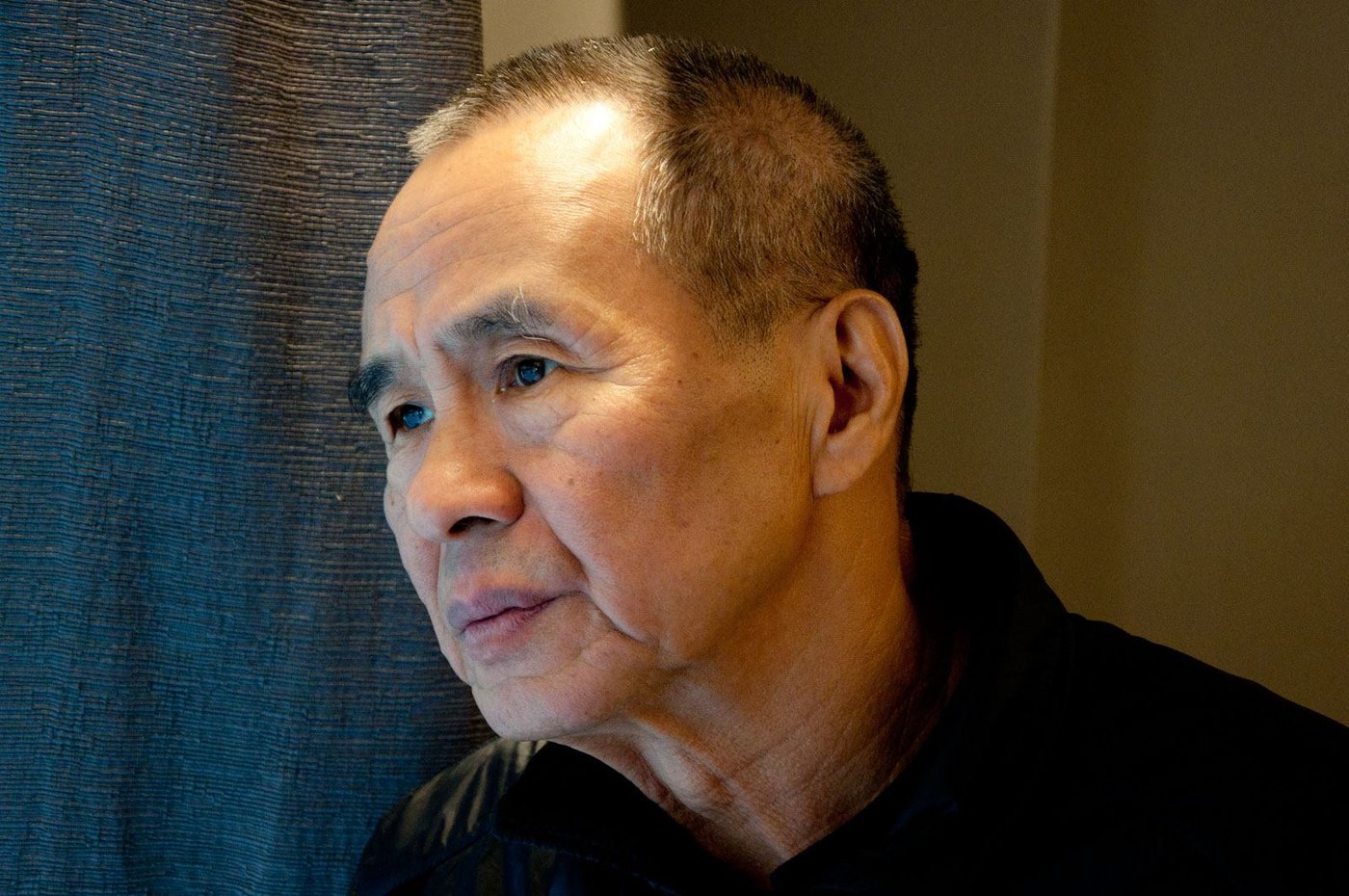

Over the course of three decades and more than 30 films, Tsai and Lee have constantly refined and simplified their methods of observation, first stripping away traditional performance styles, and then the three-act structure, and then, finally, the industrial machinery of film production. Following his last narrative feature, Stray Dogs (2013), Tsai hinted at retirement. In fact, he moved increasingly into art spaces, taking commissions for gallery work and exploring the breakthrough he had achieved in 2012 with the first of the Walker films, in which Lee, dressed in the red robes of a Buddhist monk, moves as slowly as possible through urban environments. Tsai has said that he now happily accepts his destiny, which is simply to film Lee Kang-sheng’s face. In retrospect, each step of his career seems to have been toward achieving a more pure expression of that ambition, removing all vestiges of interference between the camera and Lee’s “natural way of behaving.”

Days, which premiered in Competition at the 2020 Berlinale, marks Tsai’s return to feature filmmaking, but even compared with the sparse and elliptical Stray Dogs it is a stripped-down affair. Tsai has made oblique references to the project in recent years, mentioning only that he was filming Lee and another actor and that he no longer considered himself a screenwriter. Instead, he wanted to work without even a concept for the film in mind. As he explains in our interview, that meant, in practice, collecting images of Lee and co-star Anong Houngheuangsy, recording synch sound, and only later shaping the material into something resembling a narrative.

In the first act of Days, Tsai crosscuts between Lee and Anong living their separate, isolated lives. Lee, now in his early 50s, inhabits a number of spaces, including a spartan, modern flat, the crowded streets of Hong Kong, and what appears to be the abandoned building that Lee and Tsai have shared since they decided several years ago to move closer to nature while Lee recovered from an illness. Lee’s first major health crisis, a mysterious neck ailment, became a significant plot point in The River (1997). Two decades later, the sickness has returned, and much of Days is a deeply compassionate study of Lee struggling to manage his pain. We see him wearing a neck brace and stretching, and in one remarkable, extended sequence, he visits a clinic to receive a moxibustion treatment, which involves affixing small cones (moxa) to the top of acupuncture needles and lighting them on fire. The treatment ends with a massage-like scraping of the affected area, which causes large contusions to spread over Lee’s shoulders and back. Tsai cuts from the procedure to a close-up of Lee, who stares into the camera, twitching, his face marked on both sides by deep lines from the massage chair, like folds in his skin. It’s a monumental image and unlike any of Lee we’ve seen before.

Tsai and Anong became friends three years ago after meeting in Bangkok, where Anong has worked illegally since emigrating from Laos as a teenager. It’s impossible to not draw parallels between him and the young Lee Kang-sheng we first meet in Rebels of the Neon God (1992): silent, graceful, a strangely arresting screen presence. Tsai often films Anong alone in his home, a barren, concrete slab of a room, where he prays to a makeshift shrine and prepares his meals. The press kit for Days includes this unusually melancholy description of the actor: “Even after several years, the urban city still feels foreign, cold, and lonely to him. His only joy is meeting his Laotian friends occasionally for beer, or making a meal of hometown cuisine at home.”

An hour into Days, Lee and Anong have a pre-arranged meeting in a hotel room. Lee arrives first and removes the top blanket from the bed, folding it in a practiced gesture and setting it aside. Soon Anong joins him and gives him a massage that ends with masturbation and a passionate kiss, all in real time—two shots lasting just under 20 minutes. It’s a rare moment of relatively uncomplicated connection and pleasure in Tsai’s filmography, which seems miraculous somehow. The exchange is no less poignant for being transactional. When Anong leaves, Lee chases after him and they share one meal before returning to their lonely lives back home.

The image of Lee and Anong eating together, like much of Days, recalls the lost family unit that was so central to Rebels of the Neon God, The River, and What Time Is It There? (2001). Lu Yi-ching and Miao Tien, who played Lee’s mother and father, haunt Days with their absence, particularly in a scene after the massage, when Lee and Anong sit quietly together at the end of the bed. Days is a small, modest film, but this shot is precisely blocked and art-directed, with warm light in the foreground and cool fluorescent in the back—a delightful reminder that Tsai remains a master of traditional film form. Lee surprises Anong with a gift, a small music box that plays the theme from Chaplin’s Limelight (1952), and as they sit, listening to the tune, the nature of their relationship transforms suddenly into something more paternal and tender. A generation has passed before us on screen. The cycle is repeating. “And then you suddenly realize you are old,” Tsai told me, with a grin.

* * *

Cinema Scope: Director Tsai, I met you briefly 15 years ago in Toronto when you presented a screening of a Grace Chang film, The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin, 1960). All I knew at the time about Grace Chang was that you’d included a few of her songs in The Hole (1998) and The Wayward Cloud (2005). I remember you saying at that screening that you were nostalgic for those old Hong Kong musicals because they are full of genuine, oversized emotions. Is the music box a kind of trick for sneaking genuine, oversized emotions into Days?

Tsai Ming-liang: Yes! It’s very interesting that you started with this question! On the flight to Berlin I watched Judy (2019). Why did I watch that film? Because I love Judy Garland. After I watched it, all I could think was, “There will never be another Judy Garland!”

Cinema Scope: Do you still watch older, more sentimental films for inspiration?

Tsai: Yes, I can become very obsessed. I have an exhibition space in Taipei, where I showed the Walker films with Lee Kang-sheng. I just had a film festival there and we screened Chaplin’s City Lights (1931).

Cinema Scope: What happens when the music box is opened? What do you hope viewers will experience at that moment?

Tsai: It’s a gift! That’s a gift we all need.

Cinema Scope: Anong, in much of the film, you are doing everyday tasks like cutting vegetables and preparing food, but the music-box scene is slightly more formal. It’s a beautifully lit shot, and I imagine that room felt more like a traditional film set than the other locations. How did Director Tsai prepare you for the scene?

Anong Houngheuangsy: For the hotel scene, Director Tsai told me to just sit still, to focus on my breathing, and to be prepared to improvise. I didn’t know Kang would bring me the gift, so that was very surprising. I didn’t expect it at all. How I reacted was very natural.

Cinema Scope: How is the character different from yourself? How much are you performing?

Anong: I think I was not even acting. I was just being myself. I was cooking and sleeping and reacting exactly as I normally do. I didn’t create a new story for the character.

Cinema Scope: Lee, I think you and I are about the same age, and I’ve been watching these films for almost 25 years. Seeing you sitting on the bed beside Anong made me realize how much I miss Miao Tien. What do you remember about him? And do you feel his presence in your performance?

Lee Kang-sheng: Miao Tien played my father in The River, which was when I first hurt my neck, the first time I got sick. I’ve gotten sick again, which is what you see in Days. Twenty years later, I’ve reached the age of 51, and looking at Anong, I see that I have become the father character. Anong is like my kid. So, yes, I do find some sort of connection with Miao Tien.

Cinema Scope: Director Tsai, I’m now a father, and my own father is nearing the end of his life, so rewatching your films over the past few weeks has been very emotional for me. Much of your work is about foundational familial relationships and about the effort to better understand and sympathize with the people we love. I wonder if you are so fascinated with Lee Kang-sheng because you can project that desire onto him?

Tsai: When I was making the new film, I did not think of The River at all. But it suddenly hit me one day as I was looking at the footage that there is maybe some kind of continuous connection. I’m present in this film. I’m with them because I see these two actors as my children.

I draw inspiration for all of my films from life itself, so of course in life you see a lot of repetition. For example, the piece of music in the music box is from Chaplin’s Limelight, which I also used at the end of I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (2006), in a Chinese version. Because I’m drawing on life, the films are always overlapping. It’s repetition. There’s a cycle. And then you suddenly realize you are old!

Cinema Scope: You mentioned that you are present in Days. Are you an actual character in the film?

Tsai: I was in the film, but I cut myself out! I don’t want the film to be a documentary. It’s a narrative feature.

Cinema Scope: But there is a mysterious third character. He’s there at the acupuncture appointment, pointing out where Lee Kang-sheng is being burned, and we hear him, or someone, clear his throat near the end.

Tsai: No! It’s just people walking by. I enjoy the offscreen sounds. Everything you hear is original sound. I didn’t change them. I didn’t enhance them. I wanted to keep the sounds as they are.

Cinema Scope: You’ve said that you collected footage for a number of years and only later realized it could be fashioned into a film. There’s a mysterious shot in Days of the sun reflecting off the windows of a building. During that scene, I imagined you carrying a camera with you, capturing images as you find them. If so, what are you looking for? How do you know when an image has life in it?

Tsai: I don’t actually walk around carrying a camera, but I do follow my actor. I follow Lee Kang-sheng. In recent years we haven’t made many feature films, but we’ve made a number of short films for museums. We did theatre. We toured in Europe. I’ve been working with a young and talented cinematographer, Chang Jhong-yuan, who is very interested in filming Lee Kang-sheng and me. For example, he was there when I cared for Lee Kang-sheng while he was sick. When I looked at his images I realized I wanted to use them, but I didn’t know how exactly.

Lee Kang-sheng wanted to see a doctor, so I said I wanted to film it. He didn’t disagree, so I followed him to the doctor with the cinematographer. I felt that if I didn’t film that day, if I didn’t capture those images, then no one would ever see Lee Kang-sheng’s face and body at that moment. It sounds strange, but when he got sick there was something heartbreaking about it. I wanted to save those images.

I thought the images would be used in a museum piece, but eventually I met Anong and while we were video-chatting I saw him cooking, and the way he cooked really touched me. I wanted to film it, so I flew to Thailand. That is what I am looking for. I’m always looking for something very real.

Cinema Scope: After collecting footage for years, you had to assemble it into a film. I’m curious about that process. For example, there are several different shots of Lee Kang-sheng walking. In one sequence a handheld camera is following him through a busy street. In another, he walks alone at night under street lamps in static, long-duration shots. Do those sequences have different functions in the film? How do you decide what is necessary?

Tsai: Usually when I work on a feature film, I only use one single lens. But this time, when Lee Kang-sheng got so sick, I didn’t realize I was working on a feature. That realization came later. I was simply doing something like a documentary, just recording what was happening to him.

When we shot his visit to the clinic, we couldn’t negotiate with the doctor. We couldn’t ask for more time for a long shot. We had 30 minutes and everything happened in real time. So we shot with only one camera in a kind of panic. When Lee Kang-sheng is burned, we didn’t plan that. It was all done in a state of uncertainty.

Still, I wanted to have beautiful shots. When we walked the streets of Hong Kong, I wanted to avoid people looking at Lee Kang-sheng, so we used a hand-held camera, which of course created a different energy. But because he is so real, because he is so authentic, something powerful always comes out of it.

Cinema Scope: This was a new experiment, working without a script or even a firm concept. Do you consider it a success? Will you work like this again?

Tsai: Yes. I’m very happy with the results. I felt very comfortable in this mode. I didn’t have a big team with me this time, so I felt no pressure. I had a cinematographer and another person doing the sound, and we worked slowly, taking our time.

Of course, we had limited resources, but the cinematographer knew how to create a beautiful digital image. It takes time! But there was no pressure because I didn’t have the film industry behind my back, pressing on me. The result is something handcrafted. I’m obsessed with this way of making films.