This interview was originally published at Mubi. I collaborated on this piece with Daniel Kasman.

* * *

div>We can’t get enough of The Assassin, Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien’s first film in eight years, his first so-called martial arts film, a film set deep in the past yet bracingly present and heartbreaking. A longtime hero of ours, we sought every opportunity to speak with Hou. Thus, the strange email interview after The Assassin‘s premiere in Cannes. And thus, too, this equally strange conversation between Hou, critic Darren Hughes, and myself, where it seemed as though each participant talked past the other, our words and ideas becoming distorted in translation. We offer it to you as a small addendum to the wealth of discourse that surrounds this very special filmmaker, in general, and this film, specifically, aware of and saddened by its slim inadequacy.

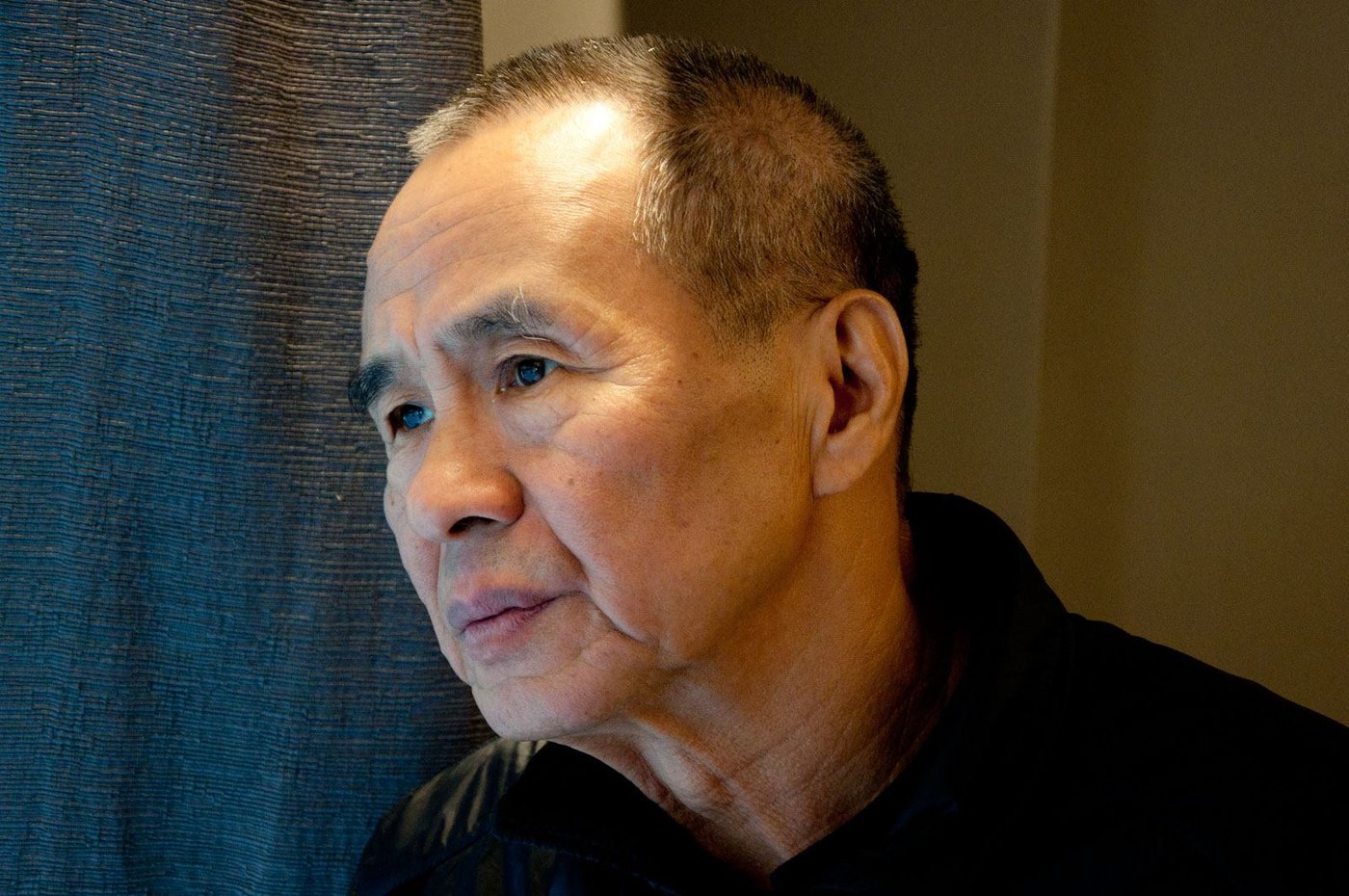

At the end of our conversation Darren requested a picture. Hou removed his ragged baseball cap, glanced quickly at the window and at the fluorescents over our heads, pushed back the curtain, and then leaned awkwardly into the natural light, giving us the photo above. That split-second gesture was a good deal more revealing of Hou’s technique than the preceding conversation.

NOTEBOOK: Many of your films are set in the past, but you’re also a strong proponent of realism in cinema. Is there a difference for you when you’re staging, say, a scene between a man and a woman in the past, as in The Assassin, or one set in contemporary Taipei?

HOU HSIAO-HSIEN: I shoot the films the same way. I give the actors short stories to read to give them a sense of how people spoke in that era, but I want them to figure it out for themselves. When making films in Asia, there is little time to give the actors a deep understanding of an era. The best I can do is a classic presentation: the way they wear their clothes, the locations.

When you see a stranger, or when you talk with someone for the first time, you’re naturally fascinated by that particular something they have. I want actors to come on set and bring that same thing. I want to capture that essence and describe it on screen. So there’s no rehearsal. The actors know what I expect of them. I allow it to sink in for the actors, but it’s not through discussion. I really want them to feel it so that when it’s time to deliver those lines it is realistic to them.

If it doesn’t work, I stop the scene and we come back to it later. For example, the scenes between Tian Ji’an [Chen Chang] and Huji [Nikki Hsin-Ying Hsieh] were not quite right [at first], so I allowed them to workshop a bit and come back to shoot those scenes again.

NOTEBOOK: Did the use of an ancient dialect for the film’s dialog transform that process in any way?

HOU: It comes down to the actors’ relationship with the language. Again, in the scenes with Tian Ji’an and Huji, I made them shoot a couple more times. But with someone like Shu Qi, who didn’t have too many lines, it was fairly easy to get into the dialect!

The actors who play the parents are from China, so they have more of a basis in the old language. They didn’t have to workshop at all. It was all very natural for them.

NOTEBOOK: The Assassin opens with a title card about events from 8th century China, and then the second sentence jumps a hundred years to the “present day” of the film. That jump reminds me of your films Good Men, Good Women [1995] and Three Times [2005] in its juxtapositions of different eras. You seem especially interested in the cinema as a historical tool.

HOU: The opening titles were not in the original cut. The French distributors told me they didn’t really understand what was going on and asked me to add an introduction. But even after adding it, I’m convinced many people still don’t understand.

Hollywood is good at telling meticulous historical stories. I’m not that kind of director. I don’t want things to be so clear. Carefully plotting every storyline, as Hollywood does, would distract from the humanity of the characters.

NOTEBOOK: There’s a moment in The Assassin when Shu Qi walks alone through the mainland countryside, and it reminded me suddenly of the young couples in Good Men, Good Women. When I described you as a historian, it’s because your films are interested in causations: what happened in the 8th century affected the 9th century, what happened in 1940 mainland China affected 1995 Taiwan.

HOU: You’re looking for a thread running through my films, for similar shots in different eras. For me, there are no connections like this. Because I’ve worked with certain actors many times, I’ve come to appreciate certain aspects of their performances, so perhaps this is the connecting line you see.

The Tang Dynasty is a very modern era. The way people lived their lives was very modern. For example, the assassin questions what it means to murder. Even if there were a time machine, it would be of no use to me because no amount of detail would overcome our modern eyes.

As I mentioned, I often work with the same actors. But when I was writing the script, I thought about incorporating other interesting people I’ve encountered. I considered casting actors from the mainland who might better encapsulate the feel of the Tang Dynasty. But I like to write with specific actors already in mind because I don’t want to arrive on set and think, “How am I going to fit your personality into my script?”

The circle of actors in Asia is fairly small. By casting Shu Qi, I knew I could give her direction and there would at least be a possibility of her changing her performance. Even though Shu Qi is not from deep in mainland China, she plays the role like an assassin, and that’s what I needed.