This essay was originally published at Senses of Cinema.

* * *

In 2018, the Toronto International Film Festival joined Sundance, Berlin, Locarno and Vienna in announcing major changes in leadership. After 36 years at TIFF, the final 24 of them as chief executive officer, Piers Handling will step down at the end of the year. Cameron Bailey, who has served as Artistic Director since 2012, retains that title and has also been named co-head of the fest, alongside new Executive Director Joana Vicente, who comes to Toronto after leading Independent Filmmaker Project (IFP) for the past decade. During his tenure, Handling steered TIFF’s course from its original, local brand, the Festival of Festivals, to its current position as North America’s preeminent showcase of new cinema and the launch pad for awards season. Handling also led the effort to conceive, fund and build the TIFF Bell Lightbox, which opened in 2010 as a permanent home for the festival, its staff and TIFF’s film reference library. In addition to providing screening venues and entertainment spaces during the festival, the Lightbox has enabled the organisation to expand its year-round programming beyond the Cinematheque repertory screenings that had, for years, been held a few blocks north at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

The very presence of the Lightbox, occupying five stories of an entire city block in Toronto’s entertainment district, is significant if for no other reason than because it represents a substantial and increasingly rare capital investment in cinema as a shared cultural and civic value. Located within short walking distance of premier museums, theatres, the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts (home of The National Ballet of Canada and The Canadian Opera Company), and Roy Thompson Hall (home of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra), the Lightbox makes real, in a physical way, Ricciotto Canudo’s century-old and still aspirational description of cinema as “the seventh art”. The nearest analogy in North America might be the founding in 1969 of The Film Society, which bestowed a particular, Lincoln Center-certified, institutional credibility not only to film exhibition and appreciation but also to the social act of film spectatorship and to cinema as an art form worthy of philanthropic support. This is becoming a recurring theme in my festival reporting: better positioning non-commercial cinema in the public and non-profit marketplaces will prove key to its long-term sustainability. That TIFF and the city of Toronto managed to pull it off amidst the transition to digital exhibition and a downtown real estate boom rather than, say, during the heydays of campus film societies is quite a feat. It’s easy to imagine someone banging his or her fist on a TIFF boardroom table in 2005 and demanding, “I know it’s a risk, but if not now, when?” Film advocates in other cities, and working at other scales of funding and ambition, should be asking the same.

TIFF’s video tribute to Handling includes footage from the 9th Festival of Festivals (1984), where he presented a landmark program, “Northern Lights: A Retrospective of Canadian Cinema”, that featured work by Jean Pierre Lefebvre, Michel Brault, Pierre Perrault, Denys Arcand, Gilles Carle, Michael Snow, Evelyn Lambert and Norman McLaren, among many others. “Northern Lights” remains an interesting historical document because it proposed a new canon – quite literally, as it was preceded by the first-ever broad polling of critics, academics, filmmakers and other industry professionals to determine the top 25 Canadian films of all time. In his program notes for “Northern Lights”, Handling sketches a brief history of Canadian cinema back to 1896, when Edison’s and Lumiere’s shorts first screened in Montreal and Ottawa, establishing from the very beginning a relationship in which, in his words, “our self-image was overshadowed by our more powerful neighbors” in America and France. Throughout the early decades of the 20th century, as the major Hollywood studios consolidated control of production, distribution and exhibition, the imbalance of power became even more pronounced: Canadians “remained foreigners within our own cinematic marketplace.” Handling’s notes for “Northern Lights” amount to a polemic and a mission statement, while also demonstrating his rhetorical and marketing talents, essential skills not to be overlooked in a festival director:

Film in Canada is undergoing significant changes in its development. . . . At this critical juncture, it is time to look back at our cinematic heritage, to see what is best, what is indigenous, what marks it as distinctive and truly ours. . . . Although we need to understand the context in which they were made, the films need no apology. In fact they constitute one of the most stimulating national cinemas in the world and are a constant source of stimulation and interest to me. Innovative, often challenging, they tell us who we are and where we life. Together they constitute a family album of extraordinary richness.1

Along with showing more than 200 Canadian films, the 1984 festival also introduced the Perspective Canada program, which in the following years would go on to promote the work and international reputations of any number of directors, including Atom Egoyan, Guy Maddin, David Cronenberg, Bruce McDonald, Deepa Mehta and Peter Mettler. In 2004, TIFF did away with Perspective Canada and began screening Canadian filmmakers alongside their international peers, but the Perspective brand lives on as the name of TeleFilm Canada’s touring film market. As an aside, during my 15 years of attending TIFF, three of my favourite experiences were repertory screenings of Michael Snow’s Wavelengths (1967), Allan King’s A Married Couple (1969) and Francis Mankiewicz’s Les bons débarras (1980), all of which screened in “Northern Lights”.

All of which is to say it is impossible to separate Handling’s legacy from the essential Canadian-ness of the enterprise he helped to build. I’m curious to see how that aspect of the organisation evolves under new leadership. Certainly Joana Vicente’s arrival seems to suggest further expansion of TIFF’s mission of showcasing and supporting Canadian filmmakers. IFP, which also operates as a non-profit, has for nearly 40 years shepherded American independent filmmakers through every stage of production, from screenwriting and financing to marketing and distribution. And like TIFF, IFP deals daily with the very practical concern of how to make profitable use (in the general sense) of brick-and-mortar facilities in a digital age. IFP’s broad portfolio of events and services – IFP Week, classes, industry talks, Filmmaker magazine, the Screen Forward Conference, the Gotham Awards, the Made in NY Media Center – offers any number of tested models for Vicente’s new board of directors to consider as they evaluate their own industry offerings, including Rising Stars, Talent Lab, Writers’ Studio and TeleFilm Canada’s Pitch This! TIFF has already begun making some efforts to augment its brand and marketing reach through all of the standard channels (YouTube, podcasts, a blog, social media), and its five-year commitment to support women filmmakers, “Share Her Journey”, is a focused and timely message around which to build a non-profit fundraising campaign.

One outcome of “Share Her Journey” was the announcement in June, made by Brie Larsen at the Women in Film Los Angeles Crystal + Lucy Awards, that TIFF would join Sundance in allocating 20 percent of press credentials to underrepresented writers. The event was held only a few days after the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at the University of Southern California released “Critic’s Choice?”, a study designed to “assess the gender and race/ethnicity of reviewers across the 100 top domestic films of 2017,” using Rotten Tomatoes as its data set. The results should come as little surprise to anyone who has attended a press screening or paid attention to review bylines:

Two-thirds of reviews by Top critics were written by White males (67.3%), with less than one-quarter (21.5%) composed by White women, 8.7% by underrepresented males, and a mere 2.5% by underrepresented females. White male critics were writing top film reviews at a rate of nearly 27 times their underrepresented female counterparts.

Andréa Grau, TIFF’s Vice President of Public Relations and Corporate Affairs, commented after the announcement: “It’s become more evident of what our role is. Festivals showcase the best cinema of the world, but we also have to showcase the range of voices talking about these films.” It’s worth mentioning that Sundance and TIFF are among a small and highly select group of international marketplace festivals whose business models are built on press coverage and, as a result, host thousands of press and industry professionals each year. I commend them for driving this conversation. They’re two of the only festivals with the clout and resources to do so.

In my report from the 2018 International Film Festival Rotterdam for Filmmaker magazine, I argued that large festivals must constantly evaluate and improve their efforts to help make independent filmmaking a sustainable career: “Until a model exists that allows those same filmmakers to mature their craft and be paid a reasonable wage while doing so – to make not just a second feature but a fifth and sixth – then a premiere screening at an oversized fest risks becoming a kind of participation trophy.” I also noted that film criticism is facing a similar sustainability crisis: “At 45, I’m often the old man in the press room, surrounded by hard-hustling freelancers. Not coincidentally, I earn my living through other means, as do many of the filmmakers I cover.” TIFF acknowledges this situation in its inclusion initiative, vowing to use money raised through the “Share Her Journey” campaign to cover travel costs for underrepresented writers. The problem is real. A few weeks after TIFF, I created a Twitter poll, asking accredited press whether they would make enough money from their writing to cover the costs of their trip to Toronto. This is hardly scientific research, but of the 130 respondents, only 21 people (16%) answered “yes”. In the interest of full disclosure, I broke even. TIFF paid for my flight and I slept on a friend’s couch, but I’m not being paid for my work, a problematic bargain I’ve made in exchange for editorial freedom and longer deadlines. I can only afford to make this bargain at my age, with children and a mortgage, because I am able to use paid vacation leave from my day job and because my partner is willing to take on all parenting responsibilities while I’m gone. Also, I’m willing to write about experimental films and festival news during my lunch hour and late at night after my kids have gone to bed.

Transparency is essential in this discussion, I think, because otherwise it’s too easy to overlook the other factors, in addition to the urgent question of inclusion, that are determining the range of voices in our critical conversation, chief among them day-to-day economics. I’m writing a few days after a group of advertisers filed suit against Facebook, alleging the company knew for years that it was overstating the amount of time users spent watching videos on the platform. Those fraudulent reports contributed directly to the industry-wide “pivot to video” that precipitated one more gutting of staff writers and editors. The consequences of this de-professionalisation of journalism, generally, and of film criticism, more specifically, are never more obvious than during TIFF. Inspired by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, I concocted a less rigorous study of my own. Over the past month I’ve read one hundred reviews of four high-profile films that I saw at TIFF: If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins), High Life (Claire Denis), The Old Man & the Gun (David Lowery) and Non-Fiction (Olivier Assayas). Like the authors of “Critic’s Choice?” I used Rotten Tomatoes as my data set, limiting my selections to reviews posted within two weeks of each film’s first TIFF screening. The results were equally stark: 64 of the reviews contain spelling, grammar and/or factual errors that would never have made it past a competent editor; only 35 of the reviews include what I would consider genuine critical insights into the film. This last metric is subjective, obviously, but I did approach the project with generosity. I was looking for anything beyond plot summaries, celebrity gossip, production histories, first-person rambles, and simple evaluation. Even a single inspired metaphor was enough to check the “critical insight” box.

I wouldn’t recommend repeating my experiment. It wasn’t much fun. On the whole, critical writing produced by accredited press during and immediately after TIFF is of poor quality more often than it’s good. To be clear, I’m in no way drawing a correlation between my criticisms and TIFF’s inclusion efforts. This has been a subject of conversation among critics, programmers, and filmmakers at every festival I’ve attended for several years now. The reasons for the mediocre writing are obvious and yet difficult to surmount. That the films are being written about is more important to TIFF’s position in the market than what is being written. In the battle for buzzworthy fall premieres, pageviews and retweets are the coin of the realm. The festival, then, is incentivised to maximise press capacity, but in order to do so it’s having to draw from a deepening pool of writers who have no reasonable expectation for a sustained career in the business. For their part, the writers are incentivised to post quickly rather than thoughtfully and accurately (pageviews!) and to trade a bit more credit card debt for the opportunity to wear a badge, see the new movies first, and be “part of the conversation”. Few will ever have the benefit of collaborating with good editors, who not only catch mistakes but challenge ideas and help to hone the craft of writing. Like the independent filmmakers they cover, too few critics will ever gain the benefits of experience. There are no simple solutions to these economic conditions, but I do hope TIFF, Sundance and other well-resourced festivals constantly evaluate their role in shaping those conditions. Press accreditation is also beginning to feel like a participation trophy.

Wavelengths Shorts

After a screening two years ago, Kevin Jerome Everson was asked a question about the seeming haphazardness of his technique. His response was along the lines of, “I’ve been doing this a long time. It’s my job. I work 40 hours a week making movies.” The man who asked the question didn’t seem to realise it was a bit patronising, and Everson’s answer didn’t take him to task for it. The guy probably came away thinking, “I was right. He shoots without much planning and then tries to find meaning in the editing.” Whereas Everson was implying, “I trust my instincts because I’ve done the work. I know where to put the camera. I know there will be wisdom in these images.” Everson’s background is in photography, which shows in his compositions, but his strength as a filmmaker has always been the integrity of his conceptual approach to each subject. When shooting Polly One, which opened the four programs of Wavelengths shorts, Everson did what millions of other Americans did on 21st August, 2017: he turned his gaze to the sky to observe a rare solar eclipse. The six-minute silent film is composed of two shots of the crescent sun, each of equal length and filmed in 16mm. In the first, the cloud cover moves quickly from right to left, presumably in a time lapse, which causes constant variations in the levels of light diffusion and in the length and shape of the lens flares that extend outward in all directions from the sun. The sky is clear in the second shot, and the lens flares are prismatic. The image is softer and more abstract, in shades of deep lavender and orange, like a Whistler nocturne. The effect of the images is coloured by the title, an ode to Everson’s grandmother, who had died a few days earlier. To assign a specific symbolic meaning to Polly One would oversimplify the viewing experience, but the film does call for ancient and out-of-fashion words to describe it, like sacramental, reverent and consecrated.

James Benning returned to TIFF for the first time in several years with L. COHEN, which was also shot during the 2017 solar eclipse. Benning has said that, although he’d read a great deal about eclipses and spent much time preparing for the shoot, he was still overwhelmed by the immediate strangeness of the experience. “I was very confused,” he told an audience at UCLA last summer. “I had a whole different sense of time. For some reason, maybe because I’m getting old, it became a metaphor for how quickly life passes. . . . It seemed very spiritual.” A few days before the eclipse, Benning drove to Madras, Oregon, the location nearest his home that would be in the centre of the shadow’s path, meaning that he would get to witness the longest possible duration of the totality, when the moon blocks out all light except for the sun’s corona. He then scouted an isolated location at the exact midpoint of the path and pointed his camera due west. L. COHEN consists of a single take, and like Polly One the film is divided in half, with the few seconds of maximum eclipse as the fulcrum. The image is of a flat, empty pasture with Mt. Jefferson in the far distance. A few objects scattered in between and a line of telephone poles at the right edge of the frame give some sense to the depth of field. (At TIFF, Benning somewhat reluctantly admitted that he’d placed a gas can in the foreground: “I thought a little yellow would look good there.”) For much of the film’s first 20 minutes, our perception is tricked both by the long duration of the gradual changes in light levels and by the digital camera’s auto-exposure, which measures and compensates for those changes, just as the eyes of the eclipse-watchers cheering somewhere off in the distance had involuntarily measured and compensated. I observed the totality of the eclipse at home with my family and, like Everson and Benning, was bewildered by the almost fearsome foreignness of the experience. When Benning plays Leonard Cohen’s “Love Itself” on the soundtrack a few minutes after the totality, it seems redundant, a faint echo of actual catharsis.

Throughout his highly productive digital period, Benning has moved constantly between galleries and the cinema. Although L. COHEN has been presented as an installation, including as part of an exhibition at the 2018 Berlinale, it strikes me as being essentially cinematic. Kudos to Wavelengths programmer Andréa Picard and everyone else at TIFF who made it possible for a fortunate group of us to watch the film in the Lightbox’s massive Theater 1. To sample just a few minutes of L. COHEN, or to see it in a room with ambient light and other distractions, or to watch it all the way through beginning at some point other than the opening moment, would undermine the film’s fundamental justifications for being. Near the end of TIFF, a friend asked, “Why are we still having to look to filmmakers in their 70s, like James Benning and Claire Denis, for big ideas and new forms?” It was a rhetorical and slightly hyperbolic question, but I understood his point. I don’t know if this is a sign of my changing tastes, or if it speaks to trends, but at the risk of having to defend a sweeping generalisation, the main difference between the best and worst films I saw in Wavelengths this year was the sophistication of the concept and assuredness of its execution. A number of short films were constructed from footage gathered by the artists without much apparent pre-determined intent. While they all included startling images – and to be fair, beauty and defamiliarisation, of course, remain worthy pursuits in experimental art – they too often lacked an essential shape or motivating force. Seeing several versions of this type of film over four nights of programming (I began to think of them as travelogues) caused them to bleed into one another in my imagination. Even Nathaniel Dorsky’s latest, Colophon (for the Arboretum Cycle), was a slight disappointment in this regard. That nearly all of them were shot on film makes me wonder if celluloid has indeed become a fetish object; shooting, processing and editing film is not, in itself, enough to justify a work. The remainder of my report will spotlight a few of the shorts that I think succeed in fully realising a compelling concept.

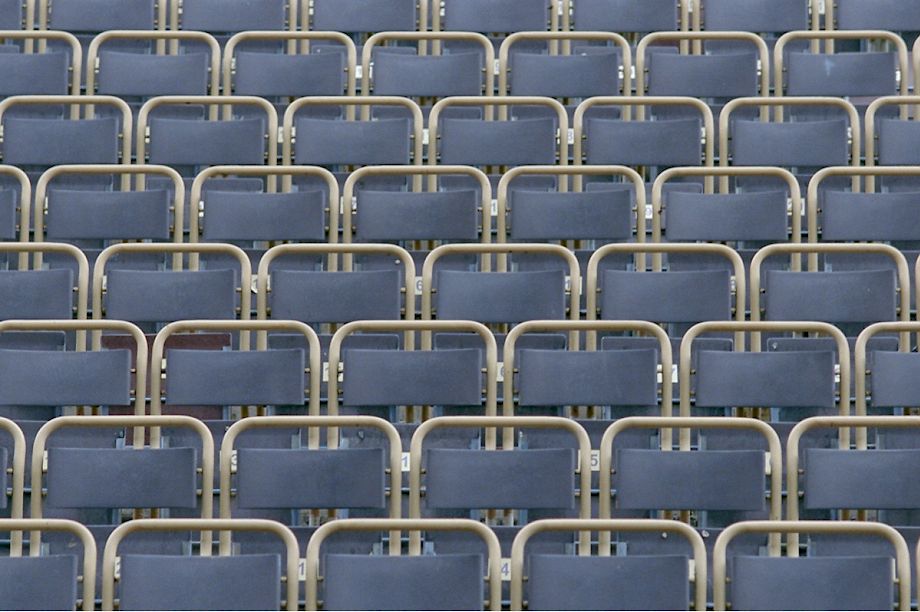

L. COHEN screened in the largest room at the Lightbox because it was preceded by Björn Kämmerer’s silent, five-minute short, Arena, which was shot in 65mm and required 70mm projection. Kämmerer has become a regular presence at Wavelengths. Navigator (2015) is a pulsing assemblage of close-ups of a rotating Fresnel lens that playfully discovers endless variations of movement and light/dark contrast. Untitled (2016) was made with even simpler means, standard-issue Venetian blinds set against a black background, which he likewise transforms into graphical elements. For Arena, Kämmerer found an unusual outdoor auditorium in the Czech Republic, where, rather than shooting the stage, he positioned his camera in the proscenium and turned it toward the seats. The film begins with a relatively tight frame (only four rows are fully visible along the y-axis) and then slowly dollies back as the entire grandstand rotates clockwise, mimicking a camera pan. Shot at 100 fps, Arena offers one more impossible perspective from Kämmerer on a familiar object. The chief pleasure of his work is the constant shifting of emphasis in our perception of the material. The seats are just seats until we begin to notice that some are slightly different colours, at which point “seats” becomes a group of individual units: one seat beside another seat, beside another, and so on. Like novice meditators, our attention can only hold that thought for a few moments, however, and soon the seats lose their specificity, become unrecognisable, and mutate, like Untitled’s Venetian blinds, into content-less shapes. Because the camera is dollying back, the frame widens gradually (by the end of the film eight rows of seats are visible) and the effects of motion parallax become more pronounced, creating visual illusions. The wide 70mm image also affords viewers uncommon freedom to explore the frame, and each time we shift the focus of our attention, new effects materialise. Whether turning the site of the subject into the spectacle is a meaningful intervention, I don’t know, but it’s a usable metaphor and a standout piece of old-school structuralism.

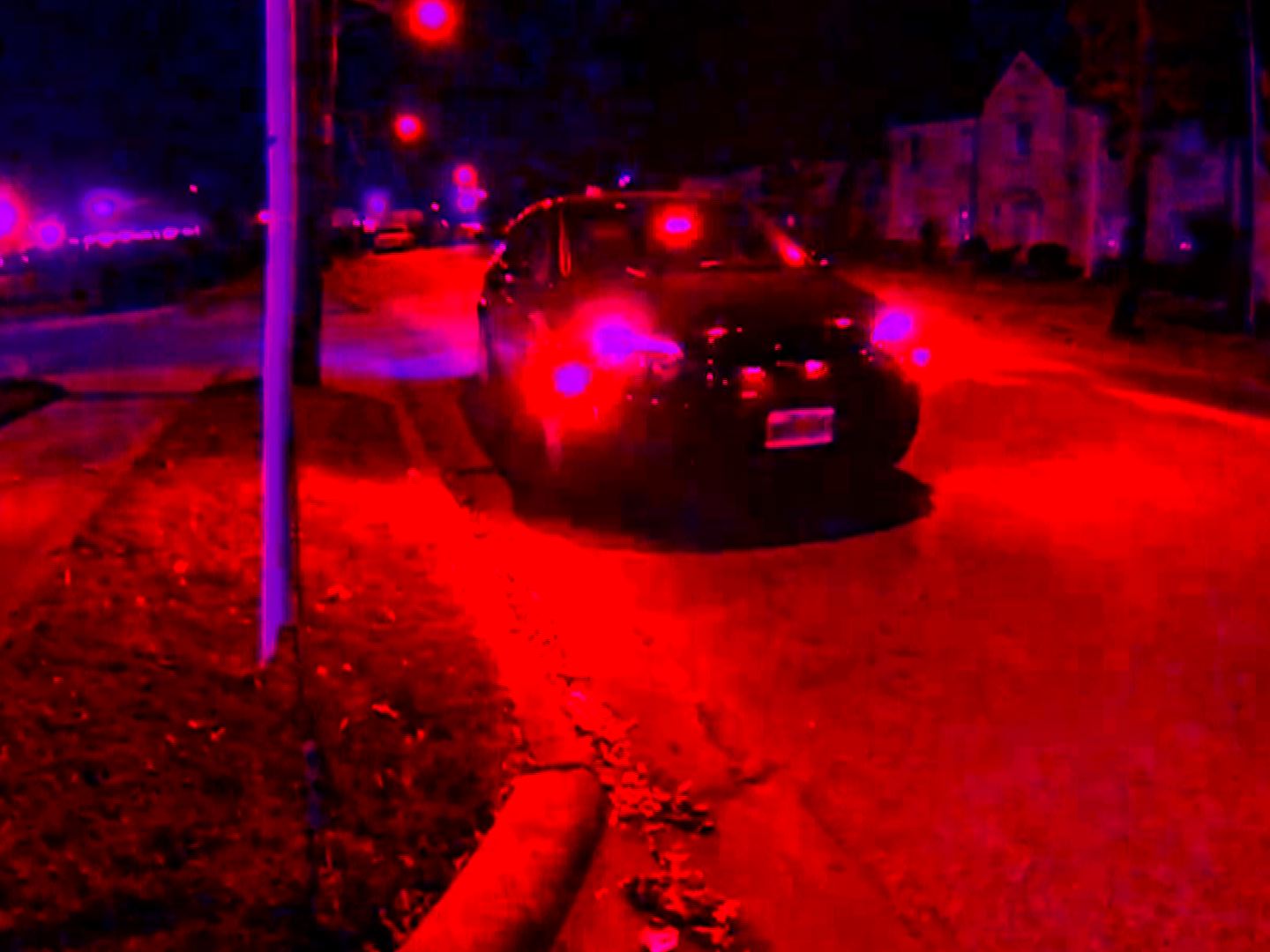

In the three years since his last feature, Cemetery of Splendor (2015), Apichatpong Weerasethakul has made several shorts, produced a documentary, and installed work at festivals and galleries in Asia, Australia and Europe. Blue, the latest of his short films to screen in Wavelengths, was developed with 3e Scène, an ambitious project of the Paris Opera that invited artists to create new work inspired, in some tangential way, by the 450-year-old institution. That context is useful, I think, when approaching a new piece by Apichatpong because the industrial bias toward feature films has limited our ability to see most of his work properly presented. Of the recent non-cinematic pieces, I’ve only experienced SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, which allowed guests in Rotterdam to check in for the night to a large room with multiple beds and a projection, all designed by the artist. His recent flurry of activity recalls Primitive Project, the collection of multimedia works he made in the late-2000s that set about unearthing the lost history and past lives of Northeast Thailand. Blue certainly evokes Phantoms of Nabua (2009), a short film from that project in which teenage boys kick a flaming ball at a park late at night, eventually igniting a makeshift screen upon which Apichatpong is projecting filmed images of manufactured lightning strikes. In Blue, Jenjira Pongpas Widner (star of many of his films) sleeps restlessly in the jungle. Her bed is arranged opposite a hanging theatrical backdrop that cycles through three illustrations. Apichatpong, like Kämmerer, puts his camera between the spectator and the spectacle, cutting between the two without fixing a clear meaning to the relationship. A fire is ignited and appears to burn from Widner’s chest. In fact, the superimposition is a centuries-old mechanical illusion: a glass positioned between her and the camera is reflecting an image of the fire. In the final shot of the film, the fire has grown large and loud. We see it in the foreground and also reflected in the glass, as if the entire jungle is burning to the ground. Widner, in the deep background, seems finally to have drifted off to sleep. Apichatpong’s particular genius is his ability to conjure the sublime from the most basic of elements – and I mean that in both senses of the word. He summons elemental sensations from commonplace sounds and practical effects: a flickering spotlight, humming insects, theatrical props, and a nighttime breeze. It’s a kind of primal magic.

Karissa Hahn exposes the basic technique of Please Step Out of the Frame in the opening shot. The first image is black-and-white Super 8 footage of a MacBook sitting on a small desk. The camera zooms in briefly toward the computer before zooming back out again, beyond the original focal distance, which reveals that the image we have been watching is itself being displayed on the screen of that same MacBook and was filmed by that same Super 8 camera from the same position at some earlier moment in time. Hahn’s film is, in short, a kind of mise en abyme as intimate, digital nightmare, and it’s tremendous fun to watch. She introduces her next trick by showing found footage of people playing with the roller coaster backdrop on Apple’s Photo Booth app. After doing so, Hahn, who we’ve glimpsed briefly interacting with the laptop, becomes the central character in the film. She herself rides Apple’s roller coaster in one clip and then adds a new custom backdrop to Photo Booth, Eadward Muybridge’s Semi-Nude Woman Hopping on Left Foot (1887). Seeing Hahn emerge, glitchy and ghost-like, from Muybridge’s photo series is deeply uncanny, and it suggests other century-old precedents for the film, particularly Lumière’s playful inventions. In one of the more unnerving moments, Hahn sits at the computer, opens a video app, and plays a screen capture of some previous version of herself interacting with the desktop. She then stands, walks behind the camera, and takes hold of the lens, zooming in so that the video on the laptop fills the entire screen, essentially erasing the diegetic world originally established in the shot and replacing it with an alternate reality. The soundtrack, like the image, is a distorted amalgam of analogue noise and digital processing – or vice-versa, I’m not sure which. Describing art as “Lynchian” is so common as to make the term useless, but Please Step Out of the Frame is a precise expression of that familiar and disquieting dread particular to David Lynch. Hahn’s film is one of the best shorts I’ve seen in recent years.

By referencing Lynch, I’ve happened upon a useful transition to Words, Planets by Laida Lertxundi, who has likewise spent much of her career thinking about how to film Los Angeles. When asked by R. Emmet Sweeney about her training at Cal Arts, she mentioned the significance of Benning’s “Listening and Seeing” course, where she learned to patiently observe a location, as opposed to claiming it like a tourist. “We weren’t allowed to shoot or record anything, just take the place in. . . . I didn’t think about shooting, but about time and landscape.” Collectively, the ten short films she’s made since then are a kind of world-building exercise, in the sense that her representation of L.A. – the geography of the city, its people, and the surrounding deserts and mountains – is so consistent and particular that it not only sidesteps the familiar cliches of Hollywood movies but imagines a wholly alternative landscape, more private but no less fantastic or dreamlike. I think of Lertxundi as a member of the Ozu camp, filmmakers whose formal preoccupations are so fixed over time that one pleasure of watching each new film is discovering small variations that suggest a maturing or complicating perspective. Her previous film, 025 Sunset Red (2016), with its allusions to her father’s political career and its incorporation of her menstrual blood as visual material, marked a shift to direct autobiography. Words, Planets pulls from her standard storehouse of images and sounds, including desert cacti, diegetic music, and the faces and bodies of friends and collaborators, while also exploring for the first time the effects of motherhood on her work: the film ends with white-on-black text that reads, “… and my life from now on is two lives.” (The infant, who appears several times in the film, is the ideal performer for Lertxundi – pure Bressonian affect!) Lertxundi has said that Words, Planets grew out of a course she teaches that begins with a reading of “For a Shamanic Cinema”, in which Raúl Ruiz proposes six strategies that interrupt the narrative machinations of industrial cinema. The suggestions, borrowed and adapted from Chinese painter Shi-T’ao, include “draw attention to a scene emerging from a static background” and “reversal of function. What ought to be dynamic becomes static and vice-versa.” I suspect it would be possible to reverse-engineer Words, Planets by assigning each shot and cut to a Ruizian strategy, but I doubt doing so would provide much insight. Rather, the point is that Lertxundi has evolved her own particular shamanic cinema. She has, in Ruiz’s words, put her “fabricated memories in touch with genuine memories [that] we never thought to see again.”

In his director’s statement for Walled Unwalled, Lawrence Abu Hamdan writes: “In the year 2000 there was a total of fifteen fortified border walls and fences between sovereign nations. Today, physical barriers at sixty-three borders divide nations across four continents.” A few minutes into the film, Abu Hamdan recites the names of every affected nation, reading them from his phone at a breathless pace while pacing from side to side a few feet away from a studio microphone. To be more precise, he’s at Funkhaus, a facility purpose-built in the 1950s to broadcast GDR state radio into West Berlin. As he races through the names, Abu Hamdan is in the second of three interconnected soundproof spaces that we see through windows from our fixed position in the darkened control room. The camera, then, is always peering through one, two, or three walls of glass: the widest shot is planimetric, which gives our view of the soundproof rooms the shape of a triptych. Abu Hamden is an artist, academic, and “audio investigator” whose various interests in the ways “we can act in the world as listening subjects” has brought him to the attention of Amnesty International and Defence for Children International as well as MoMA, the Tate Modern, Centre Pompidou and the Guggenheim. In Walled Unwalled, he delves into a central paradox of our political moment: that at the same time we’re constructing physical barriers between nations and peoples, technology has eroded the divide between personal and private space. He spins three ripping yarns – about a Supreme Court case, the murder trial of Oscar Pistorius, and a style of East German prison architecture whose acoustic design punished prisoners – but each might also have been presented as lectures (Abu Hamdan is a compelling multimedia performer) or as, say, a podcast series. Walled Unwalled, however, also succeeds as a work of cinema. The setting is essential, both thematically and as a formal device. For example, before illustrating how the Cold War-era prison design turned walls into “weapons, creating prisoners who see nothing but hear everything,” Abu Hamdan shows a clip of then-actor Ronald Reagan advocating for Radio Free Europe: “The Iron Curtain isn’t soundproof!” The clip is projected onto a wall through one of the studio’s windows, which, because of the angle of our perspective, reveals that the camera is separated from the other spaces by four thick panes of glass, each of which reflects the projection, creating multiple staggered superimpositions. Likewise, the drummer who pounds out a repeating figure through the first five-and-a-half minutes of the film in studio space three is silenced suddenly when Abu Hamdan shuts the door between the drum and the microphone in space two, walling what had been unwalled.

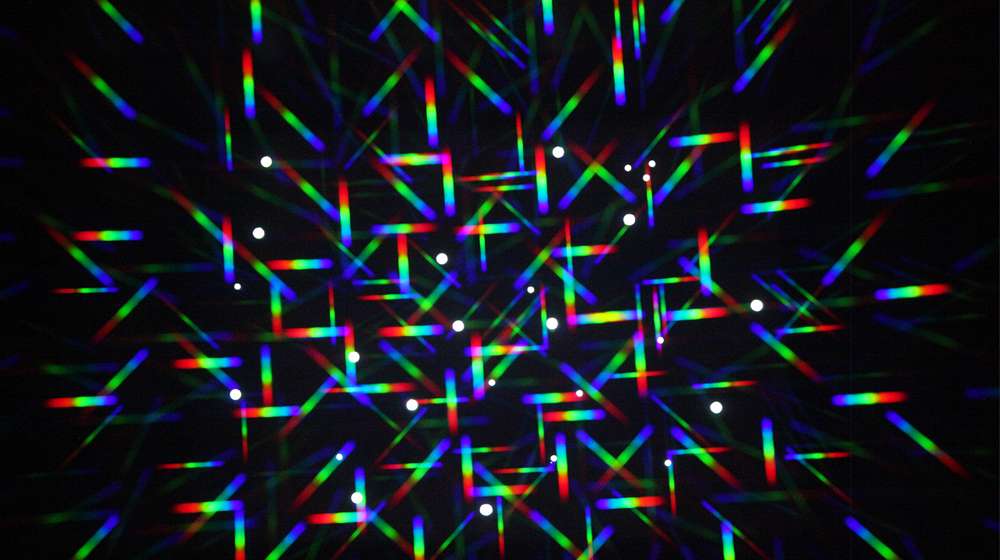

Beatrice Gibson’s I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead opens with a jagged-edge video montage of crowded subway stations, speeding trains, crumbling glaciers, violent protests, and, from time to time, in almost subliminal bursts, black-and-white home movies of her young daughter, Laizer. Over the images, Gibson describes a panic attack: “I can still feel my body except it’s like the skin is gone. It’s all nerve, edgeless, pulsating. There’s intense breathlessness. Blood is thumping. It’s like being in the club. I feel weightless. Unstitched.” Conceived soon after the election of Donald Trump, in collaboration with poets CAConrad and Eileen Myles, the 20-minute film argues forcibly, in both content and form, for the necessity of art in a time of anxiety and despair. Gibson borrows her title from CAConrad, who delivers a combative and vibrant performance of their poem of the same name. Myles reads too, and Gibson recites passages by Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde and Alice Notley. The film is scored, in part, by Pauline Oliveros. “I wanted to put all of these voices in one frame for you,” Gibson tells Laizer in voiceover, “so that one day, if needed, you could use them to unwrite whoever it is you’re told you’re supposed to be.” It’s a poignant moment because it’s so intimate, as if we’re secret witnesses to the passing down of an inheritance. The scene also captures the helpless terror of unconditional love, an aspect of parenting seldom addressed in films. Over exquisite 16mm images of Gibson alone and Laizer at play, Gibson recalls and modifies her earlier description of panic, now redeemed by love, like an act of grace: “Because of you, I am tone of voice. All nerve, edgeless, pulsating. I can breathe.” For the final act of I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead, Gibson and Laizer reenact Denis Lavant’s dance at the end of Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (1999). When I interviewed Denis a decade ago, she described the scene as the “dance between life and death.” Restaging it – complete with mirrored backdrop, disco lights, Gibson in all black, and Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night” – is an audacious and self-conscious move, obviously, but seeing it in the fall of 2018, several years into the migrant crisis and rising nationalism and after the GrenFell Fire and Charlottesville and all the rest, felt purifying somehow. That feeling of “being in the club” is cleansed of anxiety and transformed, even if briefly, into an act of joy and play. And in the process, the voices of three more artists, Claire Denis, along with Beau Travail’s cinematographer Agnès Godard and editor Nelly Quettier, are added by proxy to Laizer’s birthright.