I’m treading in deep and unfamiliar waters here. I’ve seen maybe thirty or forty films that could be considered avant-garde, and I have only the sketchiest understanding of the history and evolution of the genre. (Is “genre” even the right word? Surely not. And is there a useful distinction to be made between avant-garde and experimental films? Hopefully I’ll learn a thing or two during today’s blog-a-thon.) My goals for this post are simply to illustrate a particular formal connection I’ve noticed between two films, Phil Collins’ they shoot horses and Jon Jost’s Plain Talk and Common Sense (Uncommon Senses), and to begin exploring the potential political implications of that formal device.

First, the films . . .

they shoot horses (2004)

dir. by Phil Collins

they shoot horses is currently installed at the Tate Britain in London. I saw it there when we visited in April. Or, to be more precise, I saw twenty random minutes of it — or roughly 5% of its 6 hour, 40 minute run time. The installation itself is a room of approximately twenty feet squared, consisting of only a sound system and two projectors positioned at ninety degrees relative to one another. Both project directly onto the opposite walls, presenting viewers with two video images that, consequently, are also at ninety degrees relative to one another. Imagine standing in a large, mostly-darkened room, staring directly into one corner of it, and having your peripheral vision on both sides engulfed by competing images. Graphically, the images are similar — both are long shots of people dancing against a pink and orange striped background (see above) — but the dancers and their movements vary from side to side.

Gallery patrons hear they shoot horses before they see it; a din of break beats and pop vocals carries through much of the Tate’s contemporary art wing. In early 2004 Collins filmed two groups of teens in Ramallah as they danced all day without a break, and his installation is, in part, a visceral recreation of that moment. The low frequency thud of the disco music is as essential to the form and experience of they shoot horses as the piercing noise is to Michael Snow’s Wavelength. The only reprieves from the music come when the dance marathon is interrupted temporarily by occasional power outages and by calls to prayer from a nearby mosque. The dancers appear to have been given little instruction other than to dance and to stay more or less in the frame. I wasn’t able to watch enough of the film to describe Collins’ use of cuts (I never saw any), but the film reads as two simultaneous and continuous takes. I should also mention that, if I lived in London, I would gladly spend an entire day watching the film from start to finish. It has a simple but startling beauty.

Plain Talk and Common Sense (Uncommon Senses) (1987)

Dir. by Jon Jost

Jon Jost has described Plain Talk and Common Sense (Uncommon Senses) (1987) as a “State of the Nation discourse.” Filmed in the wake of Reagan’s 525 to 13 electoral vote trouncing of Walter Mondale, Plain Talk is a critical portrait of an America in the final throes of its decades-long ideological battle with communism. Jost systematically appropriates and deconstructs American symbols throughout the film, beginning with an opening shot of leaves of grass and ending in a grain field located at the geographical center of the nation, a grain field whose amber waves happen to flow over missile silos.

Plain Talk is an essay film that uses what I (perhaps naively) consider to be avant-garde techniques: collage (both images and sound), stop-motion photography, soundtrack manipulation, and a general preference for abstraction over narrative. Despite that preference, however, the film is rigorously structured like a traditional essay, with an introduction and nine chapters, each one building on the argument as developed in the preceding chapter. Plain Talk, as Jost writes:

asks questions, poses riddles, and prods the viewer to ponder along with the filmmaker on the meaning of it all. And, in typical American fashion, at end it plops the matter directly in the individual’s lap, following in the manner of Walt Thoreau [sic]: in the recurring parlance of the times, “You are what you eat,” or what you do. America is, in sum, what Americans do, and let be done in their name.

Plain Talk is a bit uneven. Two of the chapters, “Inside/Outside,” a send-up of Cold War America’s military and technology fetishes, and “Songs,” a travelogue of industrial excess, are more effective in theory than in practice. But I’m a great fan of the film, in general. “We hear the sound ‘America,’” Jost says in Chapter 3, “Crosscurrents,” “and instantly, without thought, our minds fill with received images.” Plain Talk is a clever, potent, and — two decades later — timely intervention that forces viewers to reconsider, thoughtfully, our images of America and our role in creating and propagating them.

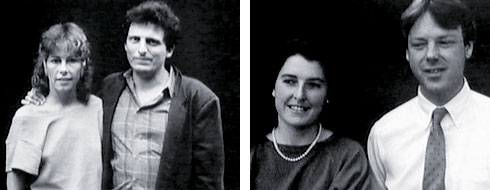

The Long Take

Chapter 7 of Plain Talk, “Americans,” is a portrait series. Each is a medium shot against a black backdrop (see above); the framing erases all visual context, leaving viewers to deduce the subject’s location and social standing from other clues, such as accent or clothes or ambient sounds (street noise in the financial district of San Francisco, chirping insects in the rural South). Although no single portrait lasts for more than twenty or thirty seconds, the shots feel longer because Jost gives his subjects no direction. They step in front of the camera and do what they’ve been trained to do over a lifetime: they introduce themselves and smile directly into the lens, slyly posing to offer the camera their best sides. But when nothing happens, panic sets in. Their eyes begin to dart from the lens to Jost, back to the lens, back to Jost. Eventually the pose drops and we get a quick glimpse of the “real” face. (The screen captures don’t do them justice, but my two favorite examples are the woman in the left image and the man in the right.)

they shoot horses has a similar effect. Over the course of the film, as Collins’ dancers become more and more exhausted from the marathon, their attitudes toward one another and toward the camera change in waves. They get bored, they lean against the wall or sit on the floor cross-legged, they flirt, they tap their toes and rock absent-mindedly, and then, from time to time, they find new stores of energy and return to their “performance,” dancing like the teenagers they see every day on satellite television.

Jost’s film is explicitly political. It’s a Leftist critique of American military and economic imperialism, and of the degradation of American democracy. Its final chapter, “Heart of the Country,” takes place in the population center of the nation, a specific geographical location that, as Jost points out, was determined by statisticians and cartographers who worked from the assumption that every citizen exerts equal weight/power. Plain Talk attacks that assumption at every turn. Though much less explicit, they shoot horses offers a similar critique by finding a formal, egalitarian beauty in the citizens of a Palestinian city under Israeli occupation. I like the description in the Tate’s program: “The work is concerned with heroism and collapse and reveals beauty surviving under duress.”

What most interests me — and what I lack a vocabulary to properly describe — is the direct connection between the form and political content in both of these films. That brief frisson that occurs when the pose drops — when a person who lives in an image-marketed and -mediated culture suddenly finds herself set adrift in the semiological flux — that moment, I think, is an instance of political resistance. It’s a temporary escape from the commodification and reification of our images and of our selves.