This interview was originally published at Filmmaker.

* * *

“My life is not what one would term heroic.”

The narrator of Romina Paula’s second novel, August, returns to her home town in Patagonia to memorialize a childhood friend five years after his death. Emilia’s in her early 20s and has been living with her brother in Buenos Aires. She’s still in college; her boyfriend is in a band. Once back home, she reunites with the love of her youth, Julián, who is now a father, married, somewhat happily. Emilia’s a familiar character making familiar first steps into adulthood, but Paula heightens every sensation and plumbs every potential cliché for wisdom. Emilia’s first-person confession is compulsive, tangent-chasing (building to a sorrowful reverie on Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny), and totally without guile. Despite her self-deprecating claim, there’s something small-h heroic about Emilia’s exhausting efforts to, as Paula told me, “affirm the questions” that are making chaos of her life.

Originally released in 2009, August is, so far, the only one of Paula’s three novels and many plays to be translated into English and published in the States (by Feminist Press at the City University of New York). In a piece for Berfrois, “Writing in Buenos Aires,” Paula details the various gigs she’s cobbled together to make her career in the arts: novelist, playwright, theater director, writing workshop instructor and actress. I first noticed her in Santiago Mitre’s The Student (2011), in which she plays a fast-talking political organizer and steals every scene. She’s better known to American audiences as a member of Matías Piñeiro’s stock company, with parts in Viola (2012), The Princess of France (2014), and Hermia & Helena (2016).

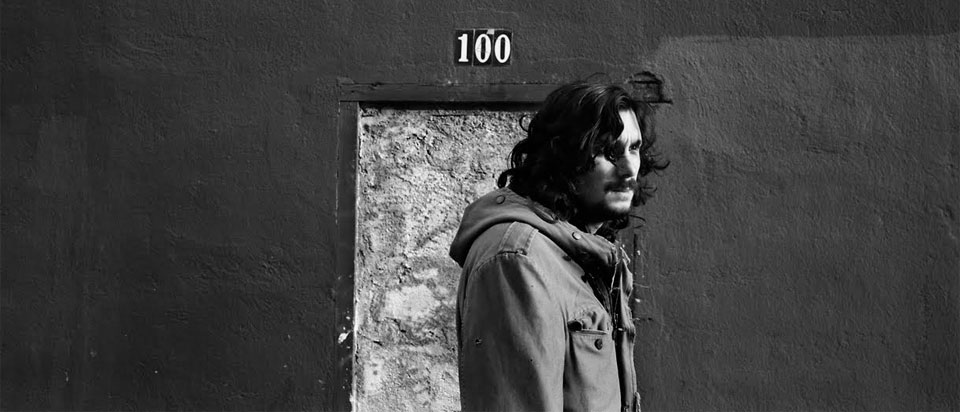

Paula has now written and directed her first film, Again Once Again (De nuevo otra vez), which is similar enough in voice and structure to be a kind of sequel to August. Paula plays a fictionalized version of herself, performing opposite her real mother and three-year-old son, Ramón. When I mentioned to Paula that I didn’t know how to refer to the heroine of the film—”should I call her Romina?”—she suggested, instead, that we call her “the character . . . so we can distinguish between the character and the director.”

Again Once Again opens with a Kodachrome slideshow. Over images of four generations of women, Paula, the character, wonders aloud whether common sense has gotten the best of her. “Maternity,” she sighs, “feels like a grail.” She and Ramón are spending a few days—or weeks maybe; there’s no firm plan—with her mother in Buenos Aires, taking some needed time away from Ramón’s father, who has remained back in Córdoba. Like Emilia, Paula’s character is stumbling through a painful period of transition. This new, “unbearable” love she feels for her son is anxiety-causing and has unsettled her relationships, ambitions and selfhood.

Again Once Again is a rich and rewarding text. The form of the film shifts constantly, often within a single shot, between the documentary reality of Paula’s family life and more traditionally scripted and performed dramatic scenes. Paula, the director and playwright, is most present in a series of monologues that interrupt and recontextualize the action of the film. Her character is not Generic Woman or Everyday Mother; she’s the particular product of a particular immigrant family at a particular moment in history, when a new feminist movement is shaking Argentina and the Internet has made condescending observers of us all. (“The whole world comments,” Paula told me. “It doesn’t experience, only comments.”) Again Once Again ends with a minutes-long, shape-shifting shot that resolves with a deeply satisfying ambiguity — one suggesting a moment of transformation, a heroic act.

I spoke with Paula at the International Film Festival Rotterdam on January 30, 2019, the day after her film’s world premiere. Again Once Again was the standout among the new features I saw there.

Filmmaker: There’s a scene early in the film in which your character gets ready to go to a party. It’s a familiar movie image: she stands in front of a mirror, trying on different outfits and putting on her makeup. But as a parent I was completely distracted by the sound of her son playing with a drum in another room. You could have edited that sequence in the exact same way without adding that sound into the mix.

Paula: In fact, there was originally more of the drums, and for me it was better, but we decided to make the sound softer. It’s not a metaphor or symbol. This is what it is to be a woman with a small child. When you try to look pretty to try to seduce someone, or for no reason in particular, already in your head there is something making noise that won’t ever stop. God willing, in the best scenario, the noise will never stop. I wanted the kid to be present in this intimate moment, which is no longer intimate.

Filmmaker: It happens again in the scene when you’re tutoring Pablo Sigal’s character. We can’t see Ramón, but we can hear him playing outside on the patio. That’s a nice shot. You and Pablo are both framed in closeup and the camera drifts back and forth between you.

Paula: If I ever do another film, I will do that shifting more often. I like that too.

Filmmaker: There are a number of one-on-one conversation scenes, and you use a variety of approaches: wide shots, traditional shot breakdowns, and that panning camera style. How did you settle on the right approach for each scene?

Paula: I had my ideas and explained how I imagined it, very basically. The assistant director and I worked on the technical plan, but then once we were on location, some ideas shifted a little bit. For me, as a theater director, it’s shocking to cut, cut, cut, because I always want to see both actors in closeup. I don’t like this about making movies. In the theater, you choose what to look at. You look at the character’s hand only, you look at the eyes, you look at the whole body. But in cinema you can’t decide as a spectator.

Filmmaker: I opened the interview with that question about the drum because it’s a specific directorial choice that makes real something you articulate in other parts of the film. In the opening voice-over you describe the psychological burden of parenting as “full-time empathy.” And later you say, “This much love can be . . .”

Paula: “. . . unbearable.” Yes. I always think about that particular phrase. When my son grows up, I want to explain to him not that I think it was unbearable to love him, which is a terrible thing to hear from your mother!

Filmmaker: I’m not Catholic, but I recently read a book by a Franciscan priest who says we each spend the first thirty or forty years of our life creating order, forming our ego. Then, eventually, we suffer a catastrophe that sends us into disorder, and at that point, we either wallow in chaos, retreat to the naive comforts of the old order, or, in a well-live life, we move through the disorder and find new meaning in the complexity.

Paula: This is nice.

Filmmaker: I only mention it because he says the two great catastrophes are tragedy and love.

Paula: At the same level!

Filmmaker: I can’t think of many films that deal with the “unbearable” love of parenting. Becoming a father wrecked my life.

Paula: Tragedy and love. Both together. Yes, you buy yourself a ticket to tragedy because you have this love, and this person you care about, and you say, “If anything happens, my life is destroyed.” So you live all of the time with that happiness and tragedy. It’s terrible. You think, “Why did I choose this? I thought it would be easier.”

Filmmaker: I joke that the moment my daughter was born was the first time I really understood I would die.

Paula: And she also is going to die. This is terrible!

Filmmaker: But I also understood deeply that in three generations, I would be forgotten, that this moment I was experiencing would be lost. I’ve described it as “nostalgia for the present”: I’m holding my kid, and I’m also eighty years old remembering when I was holding my kid.

Paula: It’s a portal. It’s true. For me, there is also this greedy thing of wanting to keep my mother and her house, and my mother with my son, which is something that’s going to be gone in a few years when she no longer exists. I don’t know if her house is going to exist anymore but it won’t in this shape. I wanted to keep that. One motivation was to film this so that I would have it. My son is not this person, already, and it was just one year ago.

Filmmaker: This all reminds me of Pablo’s monologue, when he describes Berlin as a place where time and history collapse.

Paula: I wanted to talk about the idea of diacronía and sincronía, meaning time is not like this [she holds out one hand parallel to the table, illustrating a single timeline] but like that, superimposed [she holds out both hands parallel to the table, one above the other, illustrating two simultaneous timelines].

Last winter I was in the jungle and ate an asado with a worker who was raised there by his grandparents. He didn’t know about buildings. “One lives above the other? How do you go down? With a lift? And women work? Like, cleaning houses?” At the same time, in the city I’m experiencing this feminist movement. I thought, “This is not the same chronological time.” I can’t say to this man, “You are a machista,” because that is not his experience. We are not all on the earth in the same chronological time, and who’s to say my time is the right time?

Filmmaker: There’s a late-night scene where your character and her friend Mariana (Mariana Chaud) are sitting in a park, drinking with some other people. At one point, Mariana’s younger sister, Denise (Denise Groesman), leans over and kisses your character. I love Chaud’s response. The three of you are seated very close to each other, and she immediately grabs her phone and gets a genuinely uncomfortable look on her face. I can’t decide whether it’s a performance or a documentary moment.

Paula: I don’t know either! Mariana is a very good actress, and she knew I would be kissed, so I think, somehow, she is acting it because she doesn’t care about me or the other actress. There is something concrete about two people kissing close to you. It’s uncomfortable. So it’s that combination of knowing she has to play awkward, but it was probably also uncomfortable to have kissing so close. I like this very much also, what she does. For me, the scene is about her face, not our kissing.

Filmmaker: This is your first time directing actors in front of a camera. Did you have any strategies in mind? Was it useful to draw on your experience working with actors in the theater?

Paula: I pulled more from the theatrical experience of gaining the confidence of the actors. I don’t say, “Put this here, do it like this.” It’s just being there with them. With the professional actors I didn’t use any strategies really, but I did do it with my mother. She didn’t learn the text because she’s not an actress. She was always telling me, two weeks before, “You have to tell me what I’m going to do. I need to know what to do.” The scenes were written, but I said, “No, you have to be you.”

Filmmaker: I’ve hired a professional to take photos of my children, and other people say they’re beautiful, but I don’t like them.

Paula: You don’t. Because they don’t look like themselves.

Filmmaker: Exactly. Does your mother look like your mother? Does Ramón look like Ramón?

Paula: He looks pretty much like himself. I don’t feel that strange thing when you see photos where he is prettier and you think, “This is not my kid.” Both of them, the mother and him, look like themselves.

Filmmaker: Are you aware that your mother is the only performer who doesn’t get a closeup?

Paula: No, I didn’t think about that! Now that you say it, it’s true.

Filmmaker: In your last scene with her, you’re in the foreground, slightly out of focus, and she’s in the background. I don’t mean to push this too far, but the idea of shooting my mother in closeup terrifies me somehow.

Paula: You can’t look at them closely! My mother is very expressive, and she has all of those lines in her face, like no real actress does. I like to see this very much—an older woman looking like an older woman. When we were preparing our conversations, the scenes where she has to have an emotional ride, I only told her what we would be talking about. Then when we shot we were all very quiet and were with her. It was surprising that she could do it without getting too nervous.

In our second scene, she is pushing me and I have to react. I thought, “Is she going to do it? Is she going to remember?” And she said this thing I didn’t write, “He has to have other teachers, not only us.” She invented that! Ramón is sleeping behind her [out of sight], but it’s not Ramón, of course. And at the end of the scene, she turns [and puts her hand on the stand-in]. When I saw that, I thought, “She’s a liar! I can’t believe it.”

Filmmaker: It works. I really did think, “Oh, that’s smart. They framed the shot so that Ramón doesn’t need to be there.” But when she leaned back and patted him, I wondered if he was there.

Paula: You see? She’s lying! Did she lie to me all my life?

Filmmaker: Earlier you mentioned the feminist movement in Argentina. In Denise’s monologue she retells the myth of Zeus giving birth to Athena and compares it to “the daughter’s revolution.” Did you invent that term?

Paula: No, it’s a very common term now in Argentina. If you don’t know, there’s a big fight for feminism right now. It’s not that there haven’t been other feminists, but it’s become a popular movement. A lot of young girls, very young girls, are becoming almost militant. We took this color, this green [she taps her painted green fingernails on the table], for the campaign for legal abortion. So there are a lot of new terms that are very popular. All of the girls use them, you hear them everywhere. This new vocabulary has come to us. The thing I like most about this new vocabulary is “La revolucion de las hijas” [the revolution of the daughters]/ It’s not me who invented it. The girls say that, and I like it very much. That’s why I took it.

Filmmaker: But the Athena and Zeus story is your contribution?

Paula: I looked at Athena and thought, “There must be something here. This is a feminist story.” I didn’t remember from when I studied mythology the story of her being born through her father. In fact, they don’t say this. They say, “Zeus ate the mother, and then Athena came out of his head.” It was perfect.

Filmmaker: It had never occurred to me that this turned Zeus into a mother.

Paula: By breaking his head. I like that. This is something that would happen to me when I write a book—this kind of looking, searching, drifting, until you find an idea that resonates.

Filmmaker: In the scene when you’re sitting outside talking to Pablo, there’s a moment when we see Ramón walking up very steep stone stairs in the background. I don’t know if it was scripted, but you turn your head and shoot a quick, worried glance toward him.

Paula: This was the most dangerous thing we did, the kid going up the stairs. There was someone there with him, but Ramón was going up and down alone. In reality, I would have been much more attentive. I wouldn’t have left him. It works for the scene. She’s hitting on Pablo but is not very convinced about it. She doesn’t know how to read this moment.

Filmmaker: Your worried look is another small reminder that the burden of parenting never goes away, but it’s also typical of the film in that it’s somewhere between a scripted scene and a moment of documentary reality. The film shifts constantly between four or five different formal styles. Was that always part of the design?

Paula: There was always the more documentary style with my mother and Ramón, and the scenes with actors that would be more classical, and then the slideshows. I always had them. Would you say the slideshows with voiceover and the ones with actors’ monologues are the same style? How would you subdivide them?

Filmmaker: I think they’re different viewing experiences.

Paula: So we have four already. What would you say is the fifth?

Filmmaker: The final shot, which is a more grand formal gesture.

Paula: Okay. I agree. I did it [the shifts in style] very freely. I had these images, and I was lucky that my producers let me do it. I didn’t want to be…monochromatic. I like this drifting between different perceptions or sensations.

Filmmaker: The work of a novelist is solitary and also formally limiting in some ways. Was the idea of exploring different kinds of perception part of what appealed to you about this project? Do you think of yourself primarily as a writer who also made a film?

Paula: After shooting the film and going through post-production, this work feels more like editing a book than directing the mise-en-scene of a play. I thought, “What is this? I thought cinema was more close to theater.” But what was required of me was more similar to when I write. In fact, my character, this voice, in a book would have been a first-person narrator. Not at all like theater. Not at all.

Filmmaker: You’ve worked with literary editors for years. Was that useful when it came time to collaborate with your film editor, Eliane Katz?

Paula: Eliane is very experienced. For each scene I had no more than five takes, so it wasn’t a terrible amount of material. She didn’t know me personally. She had only read the script. I told her to choose. I didn’t want to tell her which takes I preferred. She did all the work alone. It’s such a personal film—with me, my mother, my son. I shot my script, so it was too much of my look, my look, my look. I wanted someone who doesn’t know me and doesn’t particularly love me to make decisions. She needed to see a woman, her mother, and her son.

Eliane is very serious. She doesn’t say a word. She doesn’t have to. She was harsh if she needed to be; if she said something nice, I knew she meant it. I trusted her. I let her propose ideas. So she brought a cut of the film, based on the script, and it somehow worked. It was a bit long, so we took some things out, mostly scenes with Ramón. They were nice but he was taking over. This was good advice from the producers, who said, “Too much kid, too much kid, too much kid.”

Filmmaker: When I walked out of the press screening yesterday I heard two other critics saying . . .

Paula: If it’s too harsh don’t tell me.

Filmmaker: It’s a criticism but it’s not harsh.

Paula: Okay, I can hear it then.

Filmmaker: They said, “Her face is so expressive, I don’t think she needed the monologues and voiceovers.”

Paula: Oh, that’s okay. I like these critics because I think I’m not too expressive. I’ll take it as a compliment.

Filmmaker: I love slow cinema, so I’m sympathetic to their argument, but I disagree in the particular case of your film.

Paula: It all radiates from the writing, not so much from the look, the mise-en-scene: “I wrote it, now how do I shoot it?” I don’t know if I could make a movie more cinematographic, where only images tell. I don’t know. I’ve seen a lot of these films, and I love them. My characters talk because I write theater.

Filmmaker: Like I said, I’m sympathetic to the idea that a long, silent closeup has the potential to reveal something about a character that wouldn’t be expressed through dialog, but I also think it’s occasionally a convenient lie we critics like to tell each other. I appreciate that you, or your character, are trying so hard to articulate and make sense of what you’re experiencing, and your understanding evolves over the course of the film because of that effort.

Paula: This is something I do also when I write: trying to share thoughts. I don’t know maybe yet how to share thoughts without words. Although I love silence, and I like to be bored. When I write—and maybe it’s like this also in the movie—I try to find the idea by writing the same question in two or three different ways. I need to affirm the question. Here I’m also doing that: the same ideas approached in similar ways.

Filmmaker: In the second voice-over, you say there are no heroes in your family. Emilia says something similar in August: “My life is not what one would term heroic.” I wonder what you mean exactly by “heroic” and if you feel driven—in your life as an artist, a feminist, a daughter, a mother—to achieve that particular idea of heroism.

Paula: I most certainly think a lot about heroism. Heroism is always a fiction, a story designed to make a life seem exceptional. Sometimes the fiction turns a death from stupid into necessary. Other times, perhaps, it makes our everyday lives seem mediocre, giving us hope that we will become the heroic ones. I don’t know. Stories are more or less always the same, but the how isn’t. How do you say something more than what you are saying, minding the digression over the action, the anecdote? I think in the details, in the digression, there is the look of the narrator.

Maybe, when consuming heroic stories we go from general to particular, while when the reference is an everyday life story, we do the opposite, from particular to universal? When I mention heroism in the film and the book, it is never without irony. I feel that dealing with everyday life and trying not to succumb to it, not to become bitter or mean, is heroic. I also like to think of a woman’s life being heroic, without the necessity of ending it through suicide. I feel that in heroism there is always the look of “the other,” and that defining what is heroic and what isn’t is itself a moral act.