This interview was originally published at Mubi.

* * *

Midway through our conversation, Julia Loktev asked to go off the record. The plots of her two narrative features, Day Night Day Night (2006) and The Loneliest Planet (2011), turn on sudden, unexpected, transformative events, and while she’s happy to talk about the twists—“We’re so attached to this notion of spoiling, which I find a bit strange”—she’s cagier about her own points of entry into the stories, mostly for fear of ruining anyone’s fun. We agreed to keep the published interview spoiler-free.

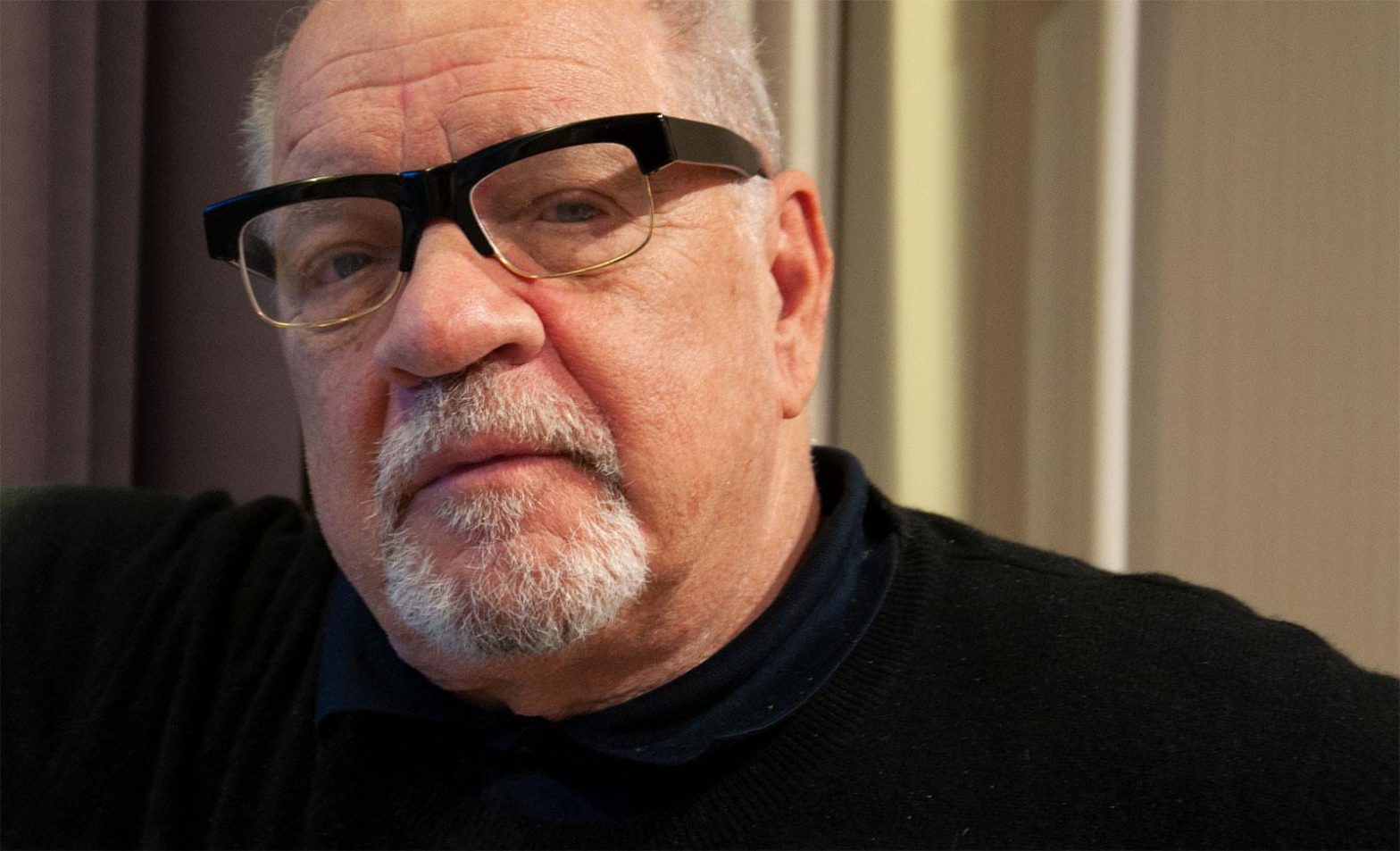

Loktev was born in St. Petersburg (then still Leningrad) and immigrated to the United States as a child. Her family settled in Colorado, where she lived until college, when she moved to Montreal to study English and film at McGill University. As a graduate film student at NYU, Loktev briefly put aside narrative filmmaking to work on a documentary feature about her father, who had been struck by a car a decade earlier. The accident, as Loktev later told Charlie Rose, left him “stuck between life and death, in a suspended state” and forced her mother to become a full-time caregiver.

Moment of Impact (1998), which earned Loktev the Directing Award at Sundance and the Grand Prize at Cinéma du Reél, is claustrophobic and intimate without ever sliding into indulgence. Loktev shot, recorded, and edited the film herself, and her parents gradually emerge in it as accommodating, if not always eager, collaborators. Indeed, the question of her father’s ability to willingly and meaningfully participate in the project is a constant tension in the film, forcing viewers to confront the same inescapable unknowing that defined so much of everyday experience for Loktev and her mother. In his 1999 review for The Nation, Stuart Klawans writes:

Surprising, inventive and canny, [Moment of Impact is] also about the emotional distance that exists between the subject of any documentary and the filmmaker – or for that matter between the subject and the audience. In some films that distance amounts to an imbalance of power, which the documentarian or the viewer is willing to exploit. Here, Julia Loktev makes the shrinking and yawning of the gap into a kind of drama – the only drama possible for people whose lives are now all anticlimax.

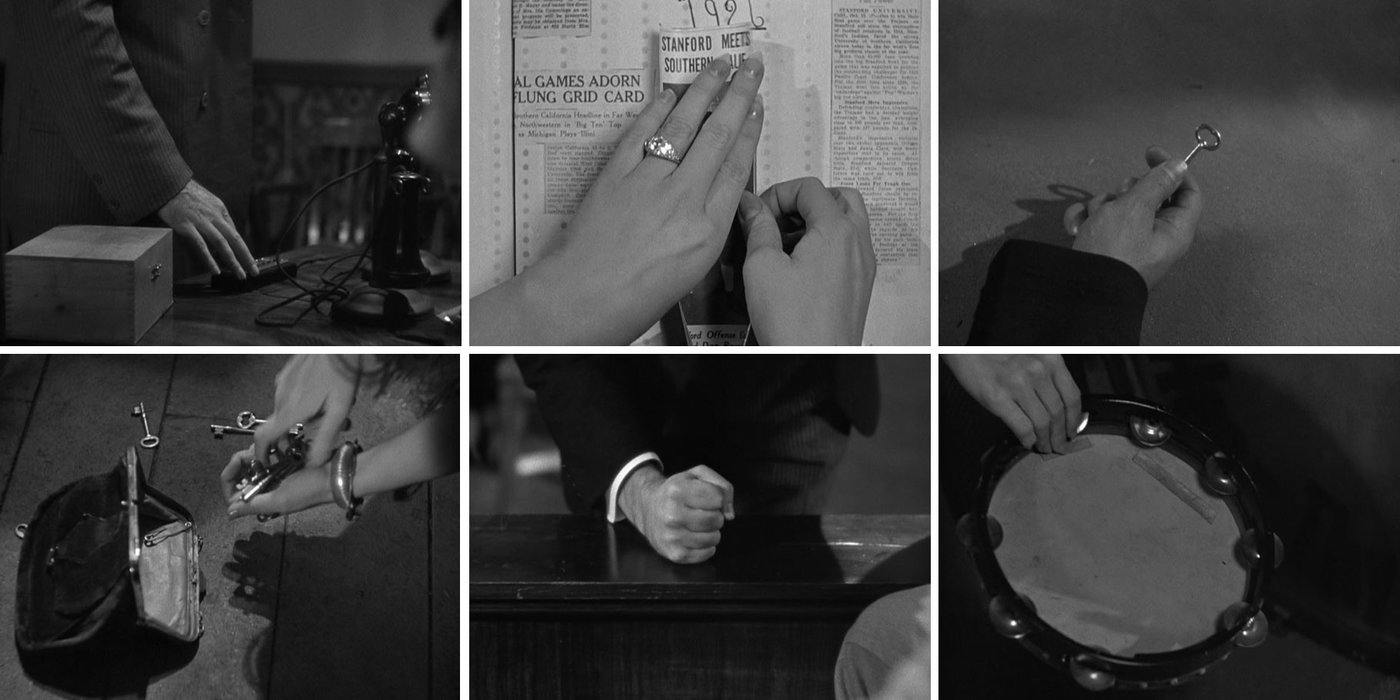

From the vantage of 2019, Day Night Day Night is something of a time capsule. Shot in HD by long-time Gaspar Noé collaborator Benoît Debie, it has all the hallmarks of that brief transition period when digital images of various resolutions were transferred to 35mm for exhibition. It remains a fascinatingly strange-looking film— monochromatic and still for the first hour, super-saturated and manic for the second. Like so many other small-budget filmmakers at the time, Loktev and Debie seem also to have been under the influence of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, whose hand-held close-ups and traveling shots redefined cinematographic “realism” in the 2000s.

Inspired by a newspaper article Loktev read while visiting Russia, Day Night Day Night documents the last two days in the life of a young suicide bomber as she makes final preparations before setting off to kill as many people as possible in the middle of Times Square. Even more provocative is Loktev’s decision to strip away every sign and symbol that might suggest a specific ideological motive for the terrorist act. First-time actress Luisa Williams responded to a flyer seeking “someone who could pass for 19 and looked ethnically ambiguous.” The nameless handlers who feed and dress her in a non-descript hotel room speak in generic, unaccented American English. The subject of the film isn’t politics or religion or nationalism but the “moral clarity” (emphasis on the scare quotes) of the would-be martyr, an idea that resonates today but was even more confrontational in 2006, three years into the Iraq War and only a few months after the London train bombing.

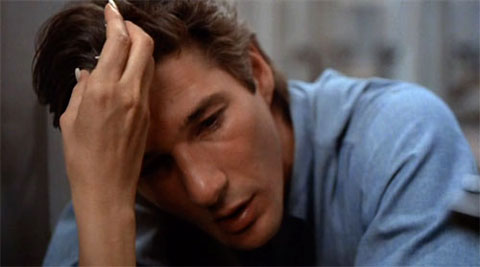

The Loneliest Planet opens with a mesmerizing image of a young woman hopping, nude and soap-covered, while her fiancé rushes to pour warm water over her. It’s the sharpest example of Loktev’s strategy of dropping us into their relationship in medias res. The signifying conversations of young love are already behind them; they’re well into the “Did you shit?” phase of commitment. While backpacking through Georgia, Alex (Gael García Bernal) and Nica (Hani Furstenberg) stop in a small village and hire a guide, Dato (Bidzina Gujabidze), to lead them on a three-day hike through the Caucasus mountains. Loktev punctuates the journey with extreme long shots of the landscape, with the horizon line always near or just above the top of the frame, which turns the hillside into flat abstraction and traps viewers in a sublime and potentially dangerous world that recalls Michelangelo Antonioni, Gus Van Sant, and Bruno Dumont.

When I first wrote about The Loneliest Planet in 2011, I described the dramatic plot twist as an “unexpectedly literary turn for a film like this, the kind of obnoxiously symbolic moment that would doom a Hemingway hero.” I was impressed at the time—and having watched the film a half-dozen times since am even more impressed now—by how masterfully Loktev and her cast rewrite that cliché. A rare film about the difficult act of reconciliation, The Loneliest Planet succeeds by choreographing the gestures, glances, and commonplace routines of intimate affection. (In that sense, it’s one of the few films I put in the same category as Claire Denis’s Beau travail.) A brief shot of Alex and Nica lying in their tent, his hand on her hip, one finger resting in the waistband of her panties, is more erotic, in the largest sense of the term, than most sex scenes I’ve watched over the past decade. As a result, the dramatic stakes in the second half of the film—they can reconcile, but will they?—are real and palpable.

Special thanks to Julia Loktev for her time. We spoke via Skype on June 20, 2019 and discussed her career so far and her immediate plans to make another film.

NOTEBOOK: Did you grow up as a cinephile?

JULIA LOKTEV: No, not really. My mom would take me to the Colorado State University film series. I remember her taking me to Stranger than Paradise and Fanny and Alexander. I think she might have taken me to Blue Velvet, or that one I might’ve figured out on my own. That was very early on, but those were formative experiences at CSU.

I was an English major with a concentration in film and communications, but I really didn’t know what I wanted to do. It started out with watching a lot of films and doing film studies classes, but then I realized I absolutely hated talking about movies after I watched them. I just didn’t want to share them. I had this very strange, selfish reaction where I hated seeing a movie and then coming out and having to analyze it with people. So I stopped taking film classes and started doing what was referred to at the time just as “theory”—that phase when post-structuralism and semiotics were fashionable. That’s what I ended up concentrating on.

Then at the same time, I was DJ’ing at the campus community station there in Montreal, and that was for me the formative experience. I’m not a musician, I’m practically tone deaf, but I’ve always loved music. It was a real evolution going from DJ’ing post-punk to discovering experimental music and what we vaguely called “radio art” at the time. I began doing my own work on the air and using that as a kind of free-for-all space, which then led to adding image to sound. So unlike a lot of people who come to film from image, I actually came from sound.

NOTEBOOK: I think we’re about the same age. College radio was really good in the late-’80s and early-’90s.

LOKTEV: College radio was really good then. This was an amazing station in Montreal. It’s actually still an amazing station. At that time, it was everything to me. The radio station was my community, much more so than the university, because it had reach throughout Montreal, and people from different communities were coming in and doing shows. It was an incredible space, and I was this girl who had moved from a fairly small town in Colorado.

NOTEBOOK: Were you collecting field recordings yourself? Or building from things you could find at the station? I remember digging through early CD collections of sound effects and royalty-free music in those days.

LOKTEV: I was going out and collecting sound. It was things that I recorded and then elements of live performance— really structured audio art pieces. At the time, we would usually record with cassettes. I remember getting my first DAT, and it was thrilling! We edited on reel-to-reel. I remember sitting there with a razor blade held between my teeth, putting the tape on the editing block and splicing it together. The transition to film made sense. There was a physicality to cutting film that was already familiar to me. I still have an old editing block around.

NOTEBOOK: What were your ambitions when you arrived at NYU for film school?

LOKTEV: I always just had this image that I would… If I could make one film, that might enable me to make another film, and that would enable me to make another film. It might be very few films, but that’s how I thought of it.

NOTEBOOK: You never considered a more commercial path?

LOKTEV: No, never. That never really crossed my mind. The films that have meant something to me have not come from that. I’ve always just wanted to make films that are like the films I love. Although I do love different kinds of movies. I love Mission: Impossible movies. But that was not the kind of film I wanted to make.

NOTEBOOK: We’re talking today partly because MUBI is showing Day Night Day Night and The Loneliest Planet this month. I wonder how you feel, in a general sense, about them today? Has your relationship to them evolved in any way?

LOKTEV: A film, once you make it, is part of you. Someone else’s film that I saw ten years ago or five years ago, I can watch again and it’s completely new. I don’t think one has that opportunity with one’s own work. It’s inherently a part of you. I don’t go back and watch it and begin again to form a relationship. It’s the relationship I had with it at the time.

Day Night Day Night

NOTEBOOK: Is there a Francesca Woodman photo on the wall of the hotel room in Day Night Day Night?

LOKTEV: No. I like Francesca Woodman, but no. In the hotel room there’s actually a reproduction of a Danish painter, Vilhelm Hammershøi, who painted empty rooms and very often the back of his wife’s head. Maybe that’s what you’re thinking of? His paintings look almost monochromatic even though they’re in color, which fit the feeling of the location. We tried to have paintings that still had the sense of something you could imagine being in a hotel room, unlike possibly a Francesca Woodman photograph! It fit the palate of the space. There’s an empty landscape that is just sky and field, and a woman from the back. He’s one of my favorite painters.

NOTEBOOK: That image of a young woman from behind is something of a signature in your films. My favorite scene in The Loneliest Planet is the long walking shot that culminates with Alex reaching out to touch a curl of hair falling over the back of Nica’s neck.

[The painting I mistook for Woodman is Hammershøi’s “Interior, Strandgade 30 (1906-8),” which can be seen by the hotel window. The larger painting over the bed is “Landscape (1900).”]

I thought Woodman made a certain sense because when I revisited Day Night Day Night, I was struck by how small—how vulnerable—Luisa Williams is. I found myself feeling worried for her, worried that she might even allow the men in the hotel room to rape her. And I’d forgotten about her encounter with the guy on the street that begins as fun and flirtatious and then gradually becomes more aggressive and threatening. I know it took you a while to cast that role. Was part of the challenge figuring out how to embody, literally, the contradictions in the character?

LOKTEV: The power dynamic was certainly something I spent a lot of time thinking about. I was very aware of her physical presence. Her manner. That was very much a part of the character. I think the phrase we used was “willful submission,” which isn’t without context. It’s not entirely personal. It is about something larger. How she walks, how she moves, the way she carries her body, the way she tries to not take up space, the way she speaks.

Usually when you get subtitles done, translators go for the content. The way she speaks in the film is, “Oh, excuse me, can I have two eggrolls please? Thank you. Thank you. Excuse me.” And the first draft of the French subtitles were, “Two eggrolls.” The scene wasn’t about the eggrolls! It was about the “Excuse me, please, may I? Excuse me, thank you, thank you.” The way she interacted with the world mattered more than the specifics, so we had to retranslate the entire film to get that sense, because that was everything.

NOTEBOOK: I’d also forgotten that Day Night Day Night was shot on digital. I saw Godard’s In Praise of Love in a theater here in Knoxville, and when it switched to the super-saturated digital images in the second section, I remember thinking, “I didn’t know a film could look like that.” Day Night Day Night has a similar effect. The primary colors in the second half are so damn beautiful.

LOKTEV: We shot on two completely different cameras. The first half was shot on a proper big camera. In Times Square, everything changes: the sound, the color, the camera, the way the camera moves. It was when HD camcorders first came out, one of the first two models, and we shot thinking we were going to transfer to 35mm.

It’s a very different physical experience when you go into a place with a giant camera versus going in with a reasonable camera. I wanted to be able to shoot in the middle of a living Times Square, where things were going on around us, where we weren’t blocking off the street, where we were just inserting ourselves into the crowd. We would hang out at a cafe until there was optimal density, and then we would go surfing in the crowd.

The first day we tried having a boom, and then that became impossible because we were moving through the crowd with Luisa, myself, and Benoît Debie. We were really just having fun. One time I nearly got Luisa killed because I’d say, “Run!” And Luisa would run and Benoît would start running with the camera, sometimes out into traffic. I’m surprised nobody ended up with broken bones because we were so focused on what we were doing and often moving, just the three of us.

NOTEBOOK: I have to admit that when I saw Day Night Day Night at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2006, I was frustrated by it. I’ll word this carefully for readers who might not have seen the film yet, but I thought some of your decisions had the potential to turn terrorism into kitsch. That was a bold move in 2006, when we were all anxiously watching coverage of the “war on terror.” Now, I’m more intrigued by how my sympathies shift as the story progresses. Much of the film is like an exercise in Hitchcockian suspense, but the last 20 minutes are something else. I’m not sure what to do with it. It’s a fascinating viewing experience.

LOKTEV: My entry point was very much tied into what happens, and how things happen, in the last 20 minutes. That’s what interested me in the story to start with. When I started out making the film, I would tell people exactly how it goes down in the last part because to me it was about the larger emotional and philosophical implications. I never set out to make a suspense film, and then people said, “You can’t give away the ending! That’s a spoiler! We want to be on the edge of our seats.” I understand that suspense is very much a part of it, but to me the film is about the way things happen towards the end.

It’s so funny, with each of these films there is a moment that people prefer to not have revealed to them before they watch the movie, but to me that’s not the crucial part. The crucial part is how everything is played out emotionally around, before, and after that moment.

The Loneliest Planet

NOTEBOOK: Is sound design still a foundation of your work?

LOKTEV: I think sound is tremendously important and very often ignored. More so than image, sound is very emotional and subjective. If you’re scared—that’s the most obvious example—how the world sounds to you when you’re afraid is very different from how it sounds when you’re secure in a space.

NOTEBOOK: There’s a perfect illustration of that idea in The Loneliest Planet. Right after the big event, the three characters hike away in single file, and you cut to them walking towards the camera, one after the other. The sound design is heightened and more present, for lack of a better word. Do you remember if that was recorded live or assembled later?

LOKTEV: Almost all of the sound in The Loneliest Planet, I’m going to say 99%, was recorded in Georgia at the time. But I would usually do a sound take and then do very detailed recordings of the space around, sometimes separately from the image. We’d do closeups of sound the same way you do of image and then reconstruct that. So it’s not that it’s created afterwards in a studio. It’s actually created from things that were of that space, at that time, but then sculpted afterwards.

If I’m remembering correctly, that scene is also a different sonic space. It’s the one section of the film where they’re walking through trees, because most of the space in Georgia was very wide open and grass. A lot of what I did in planning that film was thinking about how to compose with landscapes. We used landscapes like one would use music. We would think, “What kind of landscape makes sense here?” And the sound became an extension of that. So obviously a place with trees had more insects, it had a different kind of sound, it had a different kind of emotional feeling. And, again, how you hear things is tied to what you’re feeling at the time.

There are times when I’m very aware of my own footsteps or my own breath, to again use something very obvious that’s with you all the time. And then there are times when you’re absolutely oblivious to those sounds because your mind is elsewhere.

NOTEBOOK: Fifteen years ago I had to tell my wife that her mother and father had died unexpectedly, and I can still hear the copy machine that was spitting out paper beside us when I told her.

LOKTEV: Exactly. That makes sense to me as something you would remember. It becomes very much part of that memory. It’s the reason people often have a very hard time with interview recordings. You’re so focused on what the person is saying, and you think you can hear them, but when you listen to the recording you realize there were all these other sounds around you that you had no awareness of.

NOTEBOOK: I have to tell you this story. When I first saw The Loneliest Planet, I was surprised to find myself weeping—like, to the point that I worried the strangers around me might become concerned. I’ve been trying ever since to piece together why it had such a profound effect on me. I think it was related to the trauma of the story I just mentioned, but also I married young, and after being together for 25 years I think we’ve both learned a lot about the process of humiliating ourselves and disappointing each other and then having to figure out how to reconcile. I’ve gotten in the habit of calling The Loneliest Planet my favorite film about marriage because the question of reconciliation is so central.

As you said about the end of Day Night Day Night, I’d imagine the challenge then was figuring out how to chart the emotional journey each character takes before and after the turning point in the story. Maybe one way of approaching that is to talk about the lead performances, which are so physical and intimate and unaffected. How did Gael García Bernal and Hani Furstenberg become involved in the project?

LOKTEV: Well first, I want to acknowledge that what you just said is really lovely. That’s a very beautiful thing to hear.

I knew Gael García Bernal’s work. We connected with him through some Mexican friends of mine, who put the script in his hands and he responded to it. So that was a fairly straight-forward stroke of luck.

Hani Furstenberg is, excuse my language, a fucking genius. She’s brilliant. She’s my heart, and she’s still a dear friend. I discovered her really by chance. Early on, when I was still looking at what kind of man should play this part, somebody said, “You should look at Israeli men. Look at Israeli films. The men are macho but sensitive.” So I went looking at macho Israeli men and somehow came back with Hani Furstenberg!

I saw Hani in two movies and it took me a while to recognize her from one to the other because she transformed so completely between the movies. I was Google-stalking her for a while and discovered that she’d actually gone to LaGuardia high school in New York, was from Queens, and is American. Once I fell in love with her, I had a really hard time thinking of anyone else in the woman’s role.

Hani and I had a Georgian reunion dinner the other day with the editor, Michael Taylor, and with Lou Ford, who was the assistant editor and is now an editor in her own right and edited The Witch and The Lighthouse. We were talking about how great Hani is, and Michael said that in all the time he’s been an editor, he hasn’t really seen another actor who is so present in every take and reacting to whatever’s going on.

NOTEBOOK: My favorite example of that is a tracking shot of Alex and Nica walking along a stone wall with fresh water dripping down it. It’s after the big event. They haven’t begun speaking to each other yet. Nica walks up beside Alex and, for just a second, has this look on her face that suggests she wants to break the ice. But Alex misses the signal and she second guesses herself and keeps walking. That little gesture wrecks me because it’s so familiar. I assume you can’t direct something like that?

LOKTEV: No, no, no, that was very much Hani. She would be different in every take and really just present and responding. I’m raving about her in part because, how is she not super famous by now?

NOTEBOOK: Bidzina Gujabidze has a moment in the film that is just as impressive. Right after the event, you have all three of them in a wide shot, and Gujabidze casts this pitying glance at Alex—like, he’s embarrassed for Alex—and then he turns away, basically absolving himself of all responsibility. It’s not his problem. He’s just the hired guide! So many of the film’s central ideas intersect in that one glance.

LOKTEV: Bidzina is a professional mountaineer, and this was his first time acting. He really brought such emotional depth to that character, while, as you said, it’s a strange relationship because they’re not friends. Or, they’re friends for a few days while they go on this hike, but he’s also someone they’ve hired.

NOTEBOOK: In a 2014 interview, Gujabidze mentions that while climbing a mountain in Pakistan several of his companions were murdered by terrorists. Was that before or after making The Loneliest Planet?

LOKTEV: No, no, that was after. That was godawful. He was climbing in Pakistan and was at the second camp, while his entire team was at the first base camp. And, basically, a heretofore unknown local Al-Qaeda affiliate showed up and slaughtered all of those mountaineers. Nothing like that had ever happened there. It was horrible. [Ten mountaineers and one local guide died on June 22, 2013 in the Nanga Parbat massacre.]

NOTEBOOK: I mainly brought it up because I was so moved by one of his comments in the interview: “For a climber, danger lurks at every step, and this is why he should keep an eye on the health of others as much as on his own. Both the physical and moral condition of his fellow climber affects him directly. If a man is wicked, deceitful and treacherous, climbing the mountain will not change him.”

LOKTEV: There was this absurdity of taking Georgia’s most well-known mountaineer— he’s a celebrity in Georgia, where he would be approached on the street much more so than Gael—and having him play a regular village guide, who hikes on what the mountaineers call “the green stuff.” It’s a walk in the park for him. But he brought a lot of what he knew of the mountains to the character and to the story. I think that idea is true, even on a much less extreme expedition, that it brings out the fundamentals of who a person is. He talks about it in the film. Nature breaks things down to the basics of food, water, warmth.

The Next Film

NOTEBOOK: Can I ask if there will there be another film?

LOKTEV: Yes, you can! I’ve gone through a couple years when that would’ve been a very painful question because I got very stuck for a while. I thought I didn’t like writing, but I’m now one scene away from finishing the new script and I’m super excited about it. I’ve realized it’s not that I don’t like writing, but that writing is the only part of filmmaking that you do alone, and I actually hate working alone.

I’m co-writing a script with my girlfriend, Masha Gessen, who is a writer and journalist. It’s much broader in scope than the other films I’ve made. It takes place over ten years in three countries, in Russia, the United States, and Ireland. It’s a love story that unfolds through different phases of this relationship and through things that happen in the world around these two women. I think of the structure as like The Way We Were and Scenes from a Marriage. We’ve gone from two films that deal only with a couple of days to the story of a long relationship and the politics that surround it.

NOTEBOOK: Is this off the record?

LOKTEV: No! This is the thing I want to talk about most about. It’s funny for me to talk about old films because I’ve been in work mode, discovering the exhilaration of working again. The script is based on a lot of reporting and interviews we’ve done.

NOTEBOOK: Are you ready to throw yourself back into the world of financing and figuring out how to get it made?

LOKTEV: With the kinds of films I make, you have to reinvent the wheel every time, but I’m super excited about this.

NOTEBOOK: Do you have specific aspirations for when it will start?

LOKTEV: “Let’s cast it and shoot it!” That’s my aspiration. Sadly, the world does not work that way. I’m elated about the project, and it feels very present to me now. It’s more explicitly emotional than other things I’ve done.

NOTEBOOK: I’m now expecting a big melodrama. That’s what I’d like to see.

LOKTEV: With this one, you won’t be the only person crying in the theater.