This essay was originally published at Senses of Cinema.

* * *

On 31 December 2018, the fundraising arm of the Toronto International Film Festival sent a year-end email solicitation, urging recipients to support cinema by helping the organisation hit its annual target of 3,600 donors. This is standard practice in the non-profit world, where calendar-based tax laws are convenient tools for incentivising the philanthropic class. (I do this for a living.) I saved the email because it was addressed by Piers Handling and had a memorable subject line, “My final message as CEO.” After 36 years at TIFF, Handling was officially turning over the reins to his festival Co-Heads-in-waiting, Cameron Bailey and Joana Vicente, and entering “the next chapter of [his] life—writing, travelling, watching lots of movies.”

It makes a certain sense that Handling’s final message as CEO would be a fundraising appeal. During his tenure, TIFF expanded its mission to include year-round film programming, community initiatives, special talks and events, industry conferences, talent labs, film preservation, and more. TIFF has also worked in recent years to reshape its brand, emphasising diversity and inclusion, most prominently in its “Share Her Journey” campaign, which champions gender equality in the film industry. (36% of all films at TIFF this year were directed or co-directed by women, a new record.) In 2018, that expansion came at a total operating cost of $45 million, one-eighth of which was paid for by private donations.

Seven months later, TIFF announced the first new major event of the Bailey/Vicente era, The TIFF Tribute Awards Gala, a “fundraiser to support TIFF’s year-round programmes and core mission to transform the way people see the world through film.” Held midway through the festival at the Fairmont Royal York Hotel, the first-annual gala honoured Meryl Streep, Joaquin Phoenix, Taika Waititi, Roger Deakins, Mati Diop, and Jeff Skoll and David Linde of Participant Media, each of whom received an award and, as importantly, dressed up and made speeches in front of cameras and a room full of donors who had purchased tables for the evening. Variety was the exclusive trade media partner for the event and lent their name to the Variety Artisan Award given to Deakins. The TIFF Tribute Actor Award was sponsored by the Royal Bank of Canada. Two weeks later, Phoenix’s charming and emotional speech – ”My publicist said, ‘Someone wants to give you an award.’ I said, ‘I’m in. Let’s do it.’” – is already the fifth most-viewed clip on the TIFF Talks YouTube channel.

I mention all of this without any cynicism or eye-rolling. For more than a decade now, I’ve used these annual reports as a kind of longitudinal study of the TIFF experiment, which is impressive if for no other reason than its ambition. I titled my first piece “New Directions” because the impending debut of the TIFF Bell Lightbox and a shuffling of the programming team, including the naming of Bailey as Co-Director of the fest, were signs that 2008 would be a pivotal moment in the life of the organisation. And it was. Notably, 2008 was the first year when donors received preferential treatment in the ticket lottery system and passholders were required to pay full ticket prices for premium screenings. In the eleven years since, TIFF has grown into a full-fledged cultural institution, subsidising any number of worthy projects (hundreds of them, according to the annual report) with dollars generated in part by all of that glitz and glamour: TIFF’s earnings in 2018 accounted for 48% of total revenue, and I assume a majority of the sponsorships (another 30%) are directly associated with the festival.

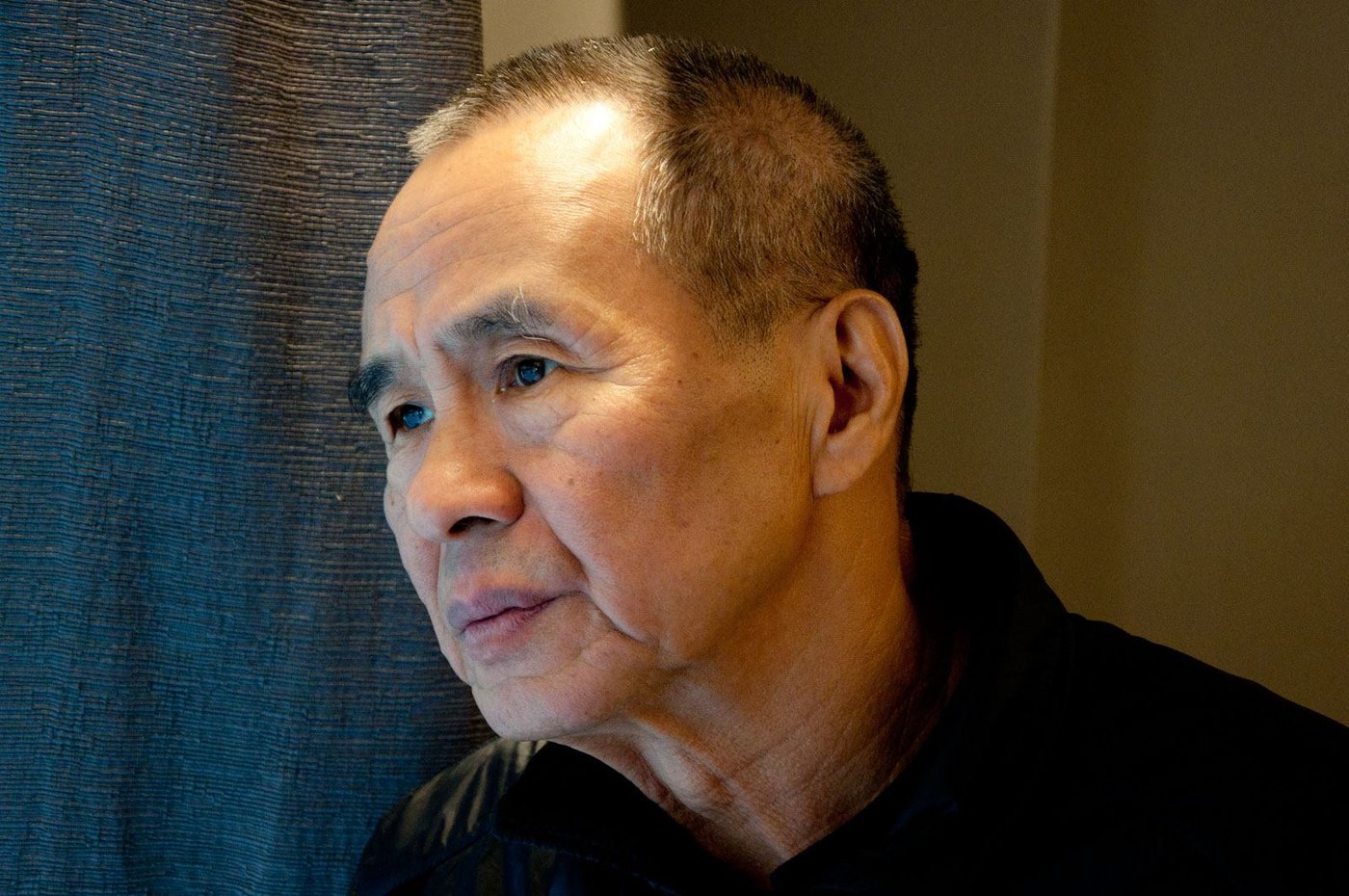

If there’s a theme to my decade of reporting it’s the growing recognition that cinema, like symphonic music, dance, sculpture, painting and opera, is a cultural value in need of public partnerships and private gift support if it is to thrive. By coincidence, I’m writing on the very day that Iowa City, Iowa (population 76,000) celebrates the opening of a new three-screen facility that boasts DCP, 35mm and 16mm projection – this, only six years after FilmScene, then a fledgling non-profit, crowdfunded $90,000 to outfit its original theatre. (They’re screening Tsai Ming-liang’s The Wayward Cloud [2005] at the moment. Just imagine!) While FilmScene’s budget is less than 2% of TIFF’s, both represent, I think, variations of the same scalable, sustainable model for repertory and non-commercial theatrical exhibition and the local cinema culture it nourishes.

The question of whether all of this growth and transformation has resulted in a better festival, judging only by the quality of the films screened, is more difficult to answer. I also noted in 2008 that two programs dedicated to boundary-pushing and formally-inventive features, Visions and Vanguard, had both been halved that year; they were soon phased out completely, with a half-dozen Vision-like slots transferred over to an expanded Wavelengths. I suspect this was as much a practical decision (simplified marketing and fewer arguments with sales agents) as it was an intentional shift away from adventurous programming, but later changes, such as the elimination of gallery installations after a particularly strong effort in 2016, suggest a general shift in the voice of the festival to align with its evolving cosmopolitan, industry-friendly and woke mission. Along those lines, in 2009 TIFF launched City-to-City, which showcased filmmakers living and working in one particular city. After a controversial start – the focus on Tel Aviv prompted a protest by a group of prominent filmmakers, artists, and actors – City-to-City carried on for seven more years, lost in the massive lineup and without making many waves, before finally being dropped. Michael Sicinski’s report on City-to-City: Seoul is an excellent discussion of the values and failings of the concept.

Handling’s final signature contribution to TIFF programming was the creation in 2015 of Platform, a relatively small, curated selection of films that, according to the original press release, was intended to champion “artistically ambitious cinema from around the world.” Bailey touted it at the time as “one of our most international programmes. . . . [It] is meant to highlight auteur cinema, directors’ cinema, at the festival.” Named in part for Jia Zhangke’s 2000 film, Platform was announced with a certain fanfare because it also introduced a new competition with a juried prize. While TIFF is already home to arguably the most important festival honour in the industry – ten of the past eleven TIFF People’s Choice Award winners were nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars; four of them won – Platform seems to have been designed in part to sustain media attention on Toronto throughout the front-loaded, eleven-day fest and to reinforce TIFF’s brand as an advocate of artist cinema.

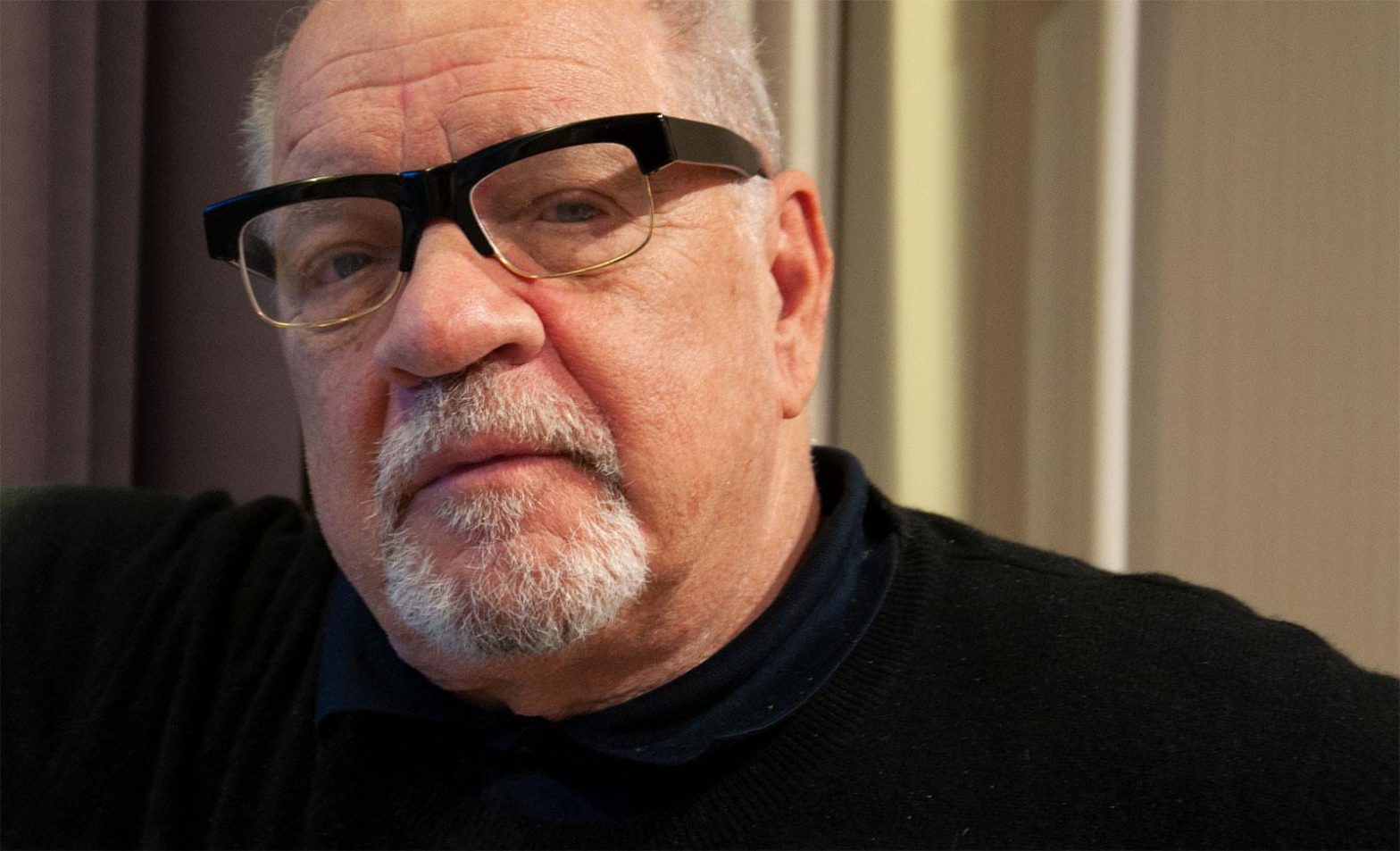

Jia was joined by Claire Denis and Agnieszka Holland on the original jury, which awarded the first Platform Prize to Hurt, by Canadian documentarian Alan Zweig. The next three juries likewise featured established international auteurs, including Brian De Palma, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, Chen Kaige, Wim Wenders, Margarethe von Trotta, Béla Tarr and Lee Chang-dong. Last year Norman Wilner of Toronto’s Now magazine asked, “Will TIFF’s Platform Prize ever take off?” Zweig, for his part, was skeptical: “I know that people in Toronto think that, given that the prize was given by Claire Denis and Agnieszka Holland, Hurt must have burned up the European film circuit. . . . As far as festivals and distribution, it’s not my least successful film . . . but it’s on the bottom with the rest of them.” As one measure of the program’s influence on international markets, Hurt is among the 20 (of 48) films that screened in the first four Platform competitions that did not find American distribution.

In hindsight, the Platform prizewinners are an idiosyncratic lot: the 2016 selection of Pablo Larraín’s Jackie over Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama and Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight has received particular attention. In his piece for Now, Wilner noted a disconnect between the average age of the jury members (at 63, Lee was the youngest member in 2018) and Platform’s mission of recognising emerging talent. Whether by coincidence or by design, the 2019 jury was younger than its predecessors and also more diverse, in terms of experience and expertise. Filmmaker Athina Rachel Tsangari, Berlinale Artistic Director Carlo Chatrian, and Variety critic Jessica Kiang were chosen, according to Bailey, to push the next evolution of the young program: “we feel incorporating established industry professionals into its jury is the natural progression.” With Handling’s departure, Bailey and long-time Wavelengths programmer Andréa Picard took over curatorial responsibilities, joined by a selection committee of Brad Deane, Ming-Jenn Lim, and Lydia Ogwang.

The consensus at the fest favoured the changes. The five Platform films I’ve seen are all commendable, although I was personally disappointed to varying degrees by four of them, including the prizewinner, Martin Eden, Pietro Marcello’s follow up to Lost and Beautiful (Bella e perduta, 2015). By relocating Jack London’s 1909 novel to some vague all-of-the-20th-century-at-once Italy, Marcello and co-writer Maurizio Braucci have made a pastiche of the specific historical conditions that shaped the despairing logic of American Naturalism, and as a result the politics of the film are a muddle. Martin Eden is stunning to look at – its found footage of a sinking ship was the most striking image I saw at TIFF. It is a big, delightfully ambitious, Capital-A Art Film, but it is always just a bit out of balance. By the time Martin (Luca Marinelli) takes the stage and delivers his first fiery address at a gathering of socialists, the over-determined plotting has caught up with it, and we’re left to ponder not the lessons of class struggle and mass culture but how to make sense of a cockeyed final act that doesn’t at all proceed inevitably from what comes before. Alice Winocour’s Proxima and Federico Veiroj’s The Moneychanger (Así habló el cambista) were among my most highly anticipated fall premieres but they both proved to be the least interesting of each director’s features. It’s especially gratifying to see Veiroj make his well-deserved debut at the New York Film Festival this year; I just wish it had been with his previous film, Belmonte (2018).

Toronto filmmaker Kazik Radwanski has screened regularly at TIFF since 2008, when his student film, Princess Margaret Blvd., made with producing partner Daniel Montgomery, premiered in the now-defunct Short Cuts Canada program. Three more of their short films and two features, Tower (2012) and How Heavy This Hammer (2015), have also played the fest, but the selection of their latest, Anne at 13,000 ft., for the Platform competition marked a formal coming out of sorts – for Radwanski and Montgomery, specifically, but also for a coterie of young Canadian filmmakers and actors who have made increasingly accomplished work in recent years.

Indeed, one of the most pleasant surprises of covering TIFF for the past decade has been observing the emergence of a talented and enterprising independent filmmaking community in the city. Many of its members have been associated with the graduate program in film production at York University, which, academic coursework aside, offers ample financial support and access to production resources, allowing students to focus full-time on the work of filmmaking for two years. Radwanski is an alumnus of the program (his thesis film, Scaffold [2017], screened at TIFF and NYFF); other current and former students include Sofia Bohdanowicz, Antoine Bourges, Andrea Bussman, Daniel Cockburn, Matt Johnson, Luo Li, Isiah Medina, Nicolás Pereda, Lina Rodriguez and Sophy Romvari. TIFF also screened new films this year by Toronto-based experimental filmmaker Blake Williams (2008) and by the team of Yonah Lewis, Calvin Thomas and Lev Lewis, whose White Lie represents a significant jump in commercial ambition and budget for the community.

Anne at 13,000 ft., which was awarded an honourable mention by the Platform jury, stars Deragh Campbell as a part-time daycare worker in crisis. Following her debut in Matt Porterfield’s I Used to Be Darker (2013) and a leading role in Nathan Silver’s Stinking Heaven (2015), Campbell has become, pardon the term, “the face” of the Toronto film scene, collaborating with Lev Lewis and Bourges, performing for and co-directing with Romvari and Bohdanowicz, and appearing on the cover of a recent issue of Cinema Scope. (The subject of the cover feature, Campbell and Bohdanowicz’s MS Slavic 7, screened at Berlin and New Directors/New Films.) Anne is a ripe role, and Campbell makes the most of it, drawing comparisons, inevitably, to Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence (John Cassavetes, 1974).

As in his first two features, Radwanski shoots his lead almost exclusively in hand-held closeups, giving viewers no choice but to experience the world through the character’s limited, subjective perspective. The technique (and I think that’s the right term for it) allows Radwanski near-complete freedom in the edit: his jump-cutting and cross-cutting strategy is built on emotional rather than classical continuity. But somewhere in the process, that continuity has been lost. Because Anne’s condition is as vague in the opening scene as in the last, and because there is so little arc in her story or in Campbell’s performance (on the simplest plot level, it seems impossible to me that this woman has been an employable childcare worker for three years when we meet her), Radwanski activates Anne’s mental illness like a suspense-making machine. Radwanski’s features are all 75-78 minutes long, which I suspect might be a measure of the limitations of his technique.

Platform opened with Rocks, directed by Sarah Gavron, who makes an interesting move here from the middling period piece, Suffragette (2015), to this finely observed and neatly made piece of social realism. The project originated with British playwright Theresa Ikoko, who, along with co-writer Claire Wilson, workshopped the story for months with children like those we see in the final film – working-class Londoners, most of them from immigrant families. Rocks turns on the lead performance by first-time actress Bukky Bakray, who embodies in every glance and gesture the exhausting, everyday pressures and lowered expectations of poverty and racism. When we first meet “Rocks”, she and her girlfriends are joking, singing and taking selfies on a highway overpass, with the city skyline behind them in the distance. She returns home from school the next day to discover that her mother has abandoned her again, leaving the 16 year-old with an envelope of cash and the responsibility of caring for her little brother, Emmanuel (D’angelou Osei Kissiedu).

This is a kind of film I’ve seen too many times at festivals over the years – one more well-intentioned “child in peril” story – but Gavron and her team of collaborators (most of them women and including the children) find new complexities and recognisable relationships in the situation. When Rocks and Emmanuel are confronted by the owner of a hostel where they’ve rented a room for the night, Savron balances a number of tensions – Emmanuel’s naive confusion and Rocks’s growing desperation but also our sudden realisation of how easily the white owner had accepted Rocks’ story that she, a black teenager, was the mother of Emmanuel, a seven year-old. Rocks was shot by Hélène Louvart, who over the past two decades has worked with Alice Rohrwacher, Nicolas Klotz, Eliza Hittman, Wim Wenders, Agnès Varda and Claire Denis, among others, and one of the great pleasures of the film is its craftsmanship. There’s wisdom in these kids’ stories, and it’s there in the form of the film too.

That Rocks was one of the few real discoveries for me at TIFF this year speaks both to the persistent frustrations of navigating such a large program (with so many established filmmakers in the lineup, it’s always difficult to justify taking chances on the unknown) and to the generally poor quality of what I chose to see. I can’t recall a weaker selection of films in my 16 years of attending the festival. Along with the Winocour and Veiroj films, I was also slightly disappointed by the latest work by Mati Diop (Atlantiques), Corneliu Porumboiu (The Whistlers), Bertrand Bonello (Zombi Child) and Kleber Mendonça Filho (Bacurau, co-directed by Juliano Dornelles). To my surprise, the three Cannes standouts were A Hidden Life, which usefully complicates Terrence Malick’s spiritual project by grounding two crises of faith in a structured narrative (Franziska Jägerstätter’s story is more interesting, I think, than her martyr husband’s); Liberté, which is not only Albert Serra’s best film but also the clearest evidence of his immense talents as a dramaturg; and The Traitor (Il traditore), in which 79 year-old Marco Bellocchio again grinds pulp material through his operatic sensibility to delirious effect: his staging of a deposition scene in a massive, prison-lined courtroom was the closest I came to cinematic ecstasy at the fest. The remainder of my report will cover a few films deserving of attention that are likely to be lost in the noise of fall festival season.

Sandra Kogut returned to TIFF with Three Summers (Três Verões), a shape-shifting comedy inspired by “Operation Car Wash”, the multi-billion-dollar money laundering and bribery scandal involving Petrobras, Brazil’s largest company, that led to hundreds of arrests and asset forfeitures. The film opens in the luxurious seaside condo of Edgar (Otávio Müller) and Marta (Gisele Fróes), where friends and family have gathered to celebrate the holidays. It’s a raucous affair, overseen as best as she can by Madá (Regina Casé), their fast-talking, perpetually optimistic housekeeper who has ambitions of her own. The only portent of trouble in the film’s first act is a mysterious phone call and Edgar’s response to it; a year later, Madá and the other workers find themselves home alone for Christmas, sipping Champagne and answering the door of a police raid. In the final act, Madá and Edgar’s aged father (Rogério Fróes) prove their moxy by finding innovative ways to monetise their situation (this being a film about the creative abuses of modern capital).

Three Summers marks a change of style for Kogut, whose previous features, Mutum (2007) and Campo Grande (2015), both examine social divisions by focusing on children who have gotten lost in the mix. This script, co-written with Iana Cossoy Paro, has the tidy, workshopped structure of a stage play, which is a less-than-ideal fit for a director whose strengths lie in observing characters in a sensory-rich world. (After seeing Mutum and The Holy Girl on early trips to TIFF, I’ve come to associate Kogut with Lucrecia Martel.) Three Summers is built around Casé’s comic persona, which is a bit of a gamble because, along with being funny and sympathetic, she is also gabby and abrasive. When, in the final act, Madá reveals the tragedies she’s overcome to create this life for herself, the scene fails to land as powerfully as one might hope because, despite Casé’s moving performance, it reads like a sample monologue in a screenwriter’s portfolio rather than the note of pathos and solidarity toward which the film seems to be building. Still, Kogut is a filmmaker worthy of greater recognition.

I will admit to taking a chance on Ina Weisse’s The Audition (Das Vorspiel) because of its star, Nina Hoss, and because of the TIFF logline: “A stern, particular violin teacher becomes fixated on the success of one of her pupils at the expense of her family life.” Hoss is, I think, one of this era’s great movie stars, and among her many gifts is an uncanny sensitivity to the power dynamics around her, both real (actor to actor, body to body) and fictitious (character to character). Always watchful and calculating, she can shift with a glance from a dominant stance to submissive, always strengthening her position in the process. Borrowing from Pauline Kael’s description of Julie Christie in McCabe & Mrs Miller (Robert Altman, 1971) Hoss also has “that gift that beautiful actresses sometimes have of suddenly turning ugly and of being even more fascinating because of the crossover. . . . the thin line between harpy and beauty makes the beauty more dazzling – it’s always threatened.” The Audition takes full advantage of both qualities.

Hoss plays Anna, a gifted violinist who has lost her confidence and, so, finds herself teaching at a Berlin high school, where she pushes her newest student to achieve the same level of excellence that she was raised to prize above all. Her son and husband have both fallen short of the mark – in Anna’s estimation, at least – so she makes proxies of her diamond-in-the-rough student and a member of the cello faculty. (The Audition is the sort of film in which metaphorical calculations are relatively simple: musical performance equals sexual performance.) The script, which, like Weisse’s first feature, The Architect (2008), was co-written by Daphné Charizani, veers inevitably into sado-masochistic territories, culminating in a long, unbroken shot in which Anna forces the boy to restart a piece of music again and again and again until his cheeks turn flush and he comes within reach of perfection. Weisse is no scold like Michael Haneke, and The Audition is not The Piano Teacher, but the final plot twist does achieve a level of audacity that is all the more transgressive for the film’s middlebrow trappings.

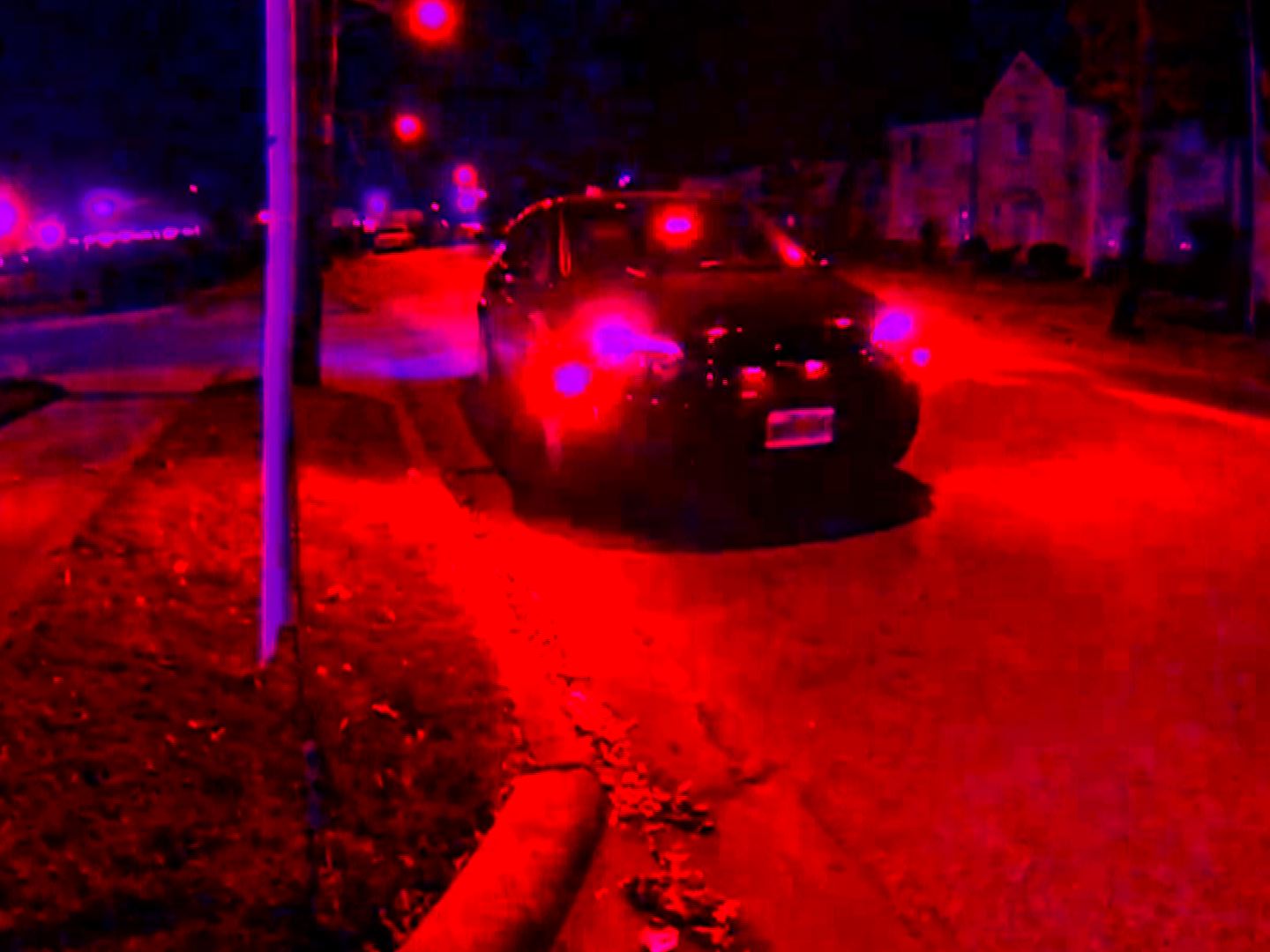

On March 6, 1953, a day after succumbing to the consequences of a stroke, Joseph Stalin was lain in state in the Hall of Columns, beginning a four-day, nationwide period of mourning that came to be known as The Great Farewell. Exactly 15 years earlier, the Hall of Columns had been the site of the notorious show trial of Nikolai Bukharin, the former Lenin associate and editor of Pravda who was soon afterward executed in Stalin’s purge of rivals. Thousands of visitors queued to pay their final respects and to catch a glimpse of Stalin’s open casket, which rested on an elevated pedestal, surrounded on all sides by ferns and dense bouquets of red and white flowers. An estimated 109 people were crushed and trampled to death in the process. In Sergei Loznitsa’s State Funeral, the image of Stalin’s body on display is unnaturally saturated, as if the colour spectrum had been reduced to only the most potent, weaponised shades of totalitarian propaganda.

Following The Event (2015) and The Trial (2018), State Funeral is the latest, and best, of Loznitsa’s found-footage reconstructions. I don’t know if there’s an exact precedent for these films, which artfully assemble rarely-seen material, in combination with original soundtracks that mimic synchronised sound (a constant murmur of voices in crowd scenes, for example) while also always drawing attention to the artificiality of the conceit. Although not nearly as long as most Wang Bing films, State Funeral likewise allows for frequent caesurae, when the content of an image sheds its familiar connotations. Nikita Khrushchev, Georgy Malenkov, Vyacheslav Molotov and Lavrentiy Beria are revealed to be uninspired speechmakers and jockeying bureaucrats. The grand bouquets and painted portraits become heavy, lumbering burdens when they are lifted awkwardly and carried to Red Square in the funeral parade. The mourners, some of them literally scarred and hobbled by war, file by the coffin in an endless procession – victims of Stalin’s cult of personality and survivors of outrageous trauma.