This essay was originally published at Mubi.

* * *

Film Forum’s 2012 William Wellman retrospective brought new and much-needed critical attention to a director best remembered today for a small handful of the 80 or so films he made between 1920 and 1958, including Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), A Star is Born (1937), Beau Geste (1939), and The Ox-Bow Incident (1943). Despite the relatively strong reputations of those films, Wellman has often been overlooked in critical discussions of Hollywood auteurs. In fact, a collection of essays that grew out of the retrospective, William A. Wellman: A Dossier, edited by Gina Telaroli and David Phelps, is the closest thing to a book-length study of Wellman currently available. After reading through much of the Dossier, I was encouraged to give Wellman a serious look myself, and this formal analysis is a small effort to continue the momentum of Telaroli’s and Phelps’s work.

Made just a few months apart and packaged conveniently on the same disc of TCM’s Forbidden Hollywood Collection, Vol. 3, Wellman’s Frisco Jenny (First National Pictures, 1932) and Midnight Mary (MGM, 1933) make for a useful case study of the director’s style. The former is a grand Greek tragedy dressed in gangster clothing; the latter is an interesting trifle, a mash-up of genres that occasionally transcends convention. On paper, the films’ scenarios are quite similar, and Wellman, who prided himself on making fast-paced films quickly (he’s credited as director on at least ten other productions in 1932 and 1933), lifts shots directly from Jenny and reuses them in Mary. The differences between the films’ formal strategies are revealing, though, and they go some way in explaining why Frisco Jenny is the much better film, both dramatically and aesthetically.

Frisco Jenny stars Ruth Chatterton in the title role as a woman raised in her father’s saloon who leaps willingly into a life of crime rather than allow her young, fatherless child to go hungry. After giving up the boy for adoption, Jenny climbs her way to the top of the criminal world, where she reigns for two decades until being convicted of murder and sentenced to death by her unknowing son, now San Francisco’s district attorney. In Midnight Mary, Loretta Young likewise takes up with a criminal gang out of desperation. During a botched casino heist, Mary meets dapper playboy Tom (Franchot Tone), who offers her a glimpse of another possible future on the straight and narrow. Veering clumsily between romantic comedy and gangland proto-noir, Midnight Mary functions first and foremost as a star vehicle for Young and Tone. Their closing-shot kiss seems less inevitable than contractually obligated.

Composing Power

Jenny and Mary are pre-Code heroines who move with varying degrees of freedom through a world dominated by men, and the exact, moment-to-moment status of their power in any given relationship can be charted with a kind of geometric precision. Here, for example, we see Jenny and one of her most trusted allies in a traditional shot breakdown: two-shot / medium close-up / reverse.

This more intimately staged conversation between Mary and her childhood friend Bunny (Una Merkel) takes the same basic shape.

Women are allies in these films. There’s no cattiness, petty jealousies, or intrigues threatening to divide them, and Wellman reinforces that solidarity in his balanced compositions. Here, for example, are two typical conversations between women in Frisco Jenny. Note that they’re staged perpendicular to the camera and that, because they sit together or stand together, their eyelines all run more or less along a horizontal plane.

Relationships between women and men are a different matter. At the most basic level, power can be measured in these compositions as a king-of-the-hill battle for the top of the frame, as in these confrontations between our heroines and the criminals in their lives, Steve (Louis Calhern) and Leo (Ricardo Cortez).

The most interesting example of this occurs in the third act of Frisco Jenny, when she is at the peak of her powers. Steve enters from the back of the room, towers briefly over her (Calhern was more than a foot taller than Chatterton), and then sinks into an absurdly short chair. I can almost imagine Chatterton sitting on a phone book here.

At times the calculus gets much more complicated. Of the two, Midnight Mary is the more conventional studio production, with on-the-nose musical cues, rapid-fire montages, and glamour. (I suspect this reflects the differences between First National’s and MGM’s production styles at the time.) Young is seldom king of the hill, yet she still dominates every frame thanks to her key light and those legendary eyes. While often challenged by men, Mary remains composed in a position of glamorous, seductive power.

Despite the fact that Midnight Mary opens with a jury deliberating over her murder charge, Mary’s fate is never truly in the balance. Wellman’s style makes this much clear: Midnight Mary is not that kind of movie; Mary and Tom will find a way out of this jam.

By comparison, Jenny is never allowed a moment’s rest. Although she has a child outside of marriage and begins her criminal career as a madam, Jenny is desexualized and denied the same powers that rescue Mary. These two shots are especially instructive.

In both scenes, the heroine is receiving bad news from someone she loves, but Wellman shoots them as mirror images. The difference is crucial, as we tend to read images from left to right. Mary is acting against Tom; Jenny is being acted upon by her father. If you scroll up to the previous screen captures you’ll see that Mary is on the left side of each frame. Jenny is always on the right. With very few exceptions, this is true throughout both films.

Looking and Listening

Something even more interesting is happening in those mirror images, though. In the first example, we look at Loretta Young as she is told bad news. In the second, we watch Ruth Chatterton as she listens. It’s a small but significant difference that exemplifies the perspectives of both films. Midnight Mary is objective (we look at); Frisco Jenny is subjective (we experience through). At the risk of oversimplifying, it’s the difference between comedy and tragedy, as demonstrated in these two nearly identical compositions, below. In the first, we, along with everyone else in the court room, turn to look at Mary, who is casually reading an issue of Cosmopolitan. It’s a nice little gag. In the second, Jenny listens intently as her son attacks her character and seals her fate.

Looking at beautiful women has, of course, been a defining characteristic of the movies—and of commercial cinema, in particular—since its earliest days. In Midnight Mary, it’s also a running theme. Again, the film is a star vehicle for then-20-year-old Loretta Young, so we should perhaps expect a few lingering shots of those knockout gams. It’s worth noting that in the following example, we participate in the old lawyer’s ogling, thanks to an eyeline match.

Wellman very seldom shifts the perspective to Mary’s subjectivity, but the film’s most compelling scene is an interesting exception to this rule. Knowing that Leo plans to leave their apartment to murder Tom, Mary first tries to keep him there by seducing him. But when her standard tactics fail, she’s forced to shoot.

Leo’s body convulses on the floor as the rest of his gang try to force open the door. It’s a grotesque image heightened by chaotic music coming from the other room, all of it filtered now through Mary’s traumatized subjectivity. Note how the camera has shifted to her left, forcing her to the right side of the frame. Her eyes stare in shocked disbelief and her head recoils with each loud knock at the door. The sequence is shockingly perverse, recalling the finale of Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931), when James Cagney’s bound body hits the floor. Leo’s death, and Mary’s horrific experience of it, stain Midnight Mary‘s “happy” ending with an unsettling and lingering ambiguity.

We seldom look at Jenny in quite the same way we look at Mary. Rather, Wellman co-opts Jenny’s perspective in the opening moments of the film and remains fixed there throughout. As a result, Frisco Jenny is as rich a film, both psychologically and emotionally, as any I can think of from the era. Eighty years later, Wellman’s style is strikingly au courant. His subjective camera reminds me less of Hitchcock’s experiments with suspense than a Claire Denis fantasia. The following two shots, for example, serve simple narrative functions, but the mise en scène transcends the script, granting the viewer special access to Jenny’s inner life. In both cases she steps silently to the foreground while everyone behind her dissolves into a tableau. The image on the right is an especially unnatural moment, as the social workers who have come to collect her son pause motionless and out of focus, allowing us to watch in silence for a few seconds as Jenny thinks.

Eternal Gestures

Jenny: Steve said the gods must be out to lunch.

Amah: No, the gods see everything. Everything in this world is balance.

That we experience the world of Frisco Jenny through the heroine’s subjectivity is more than some cinematic parlor trick. Wellman’s style turns Jenny’s world into a holy space—holy, rather than just moral—and the critical language necessary to describe it must be borrowed from discussions of transcendental filmmakers. (It’s an odd claim, I know, but after watching it several times now, I’m comfortable calling Frisco Jenny one of America’s mainstream contemplative masterpieces.) Both Jenny and Mary have run-ins with preachers and the Salvation Army along the way, but, as with the courtroom scene, Midnight Mary treats faith and spirituality as one more joke (and worse, a pat symbol) while Frisco Jenny builds a thick, knotted context in which the film’s central tragedy might find meaning and catharsis.

Frisco Jenny is probably best remembered today for its depiction of the 1906 earthquake. It strikes just as Jenny confesses to her father that she plans to marry Dan, the saloon’s piano player, and is carrying his child. A beam falls and kills her father, but before she escapes to safety, Jenny reaches down and strokes his cheek.

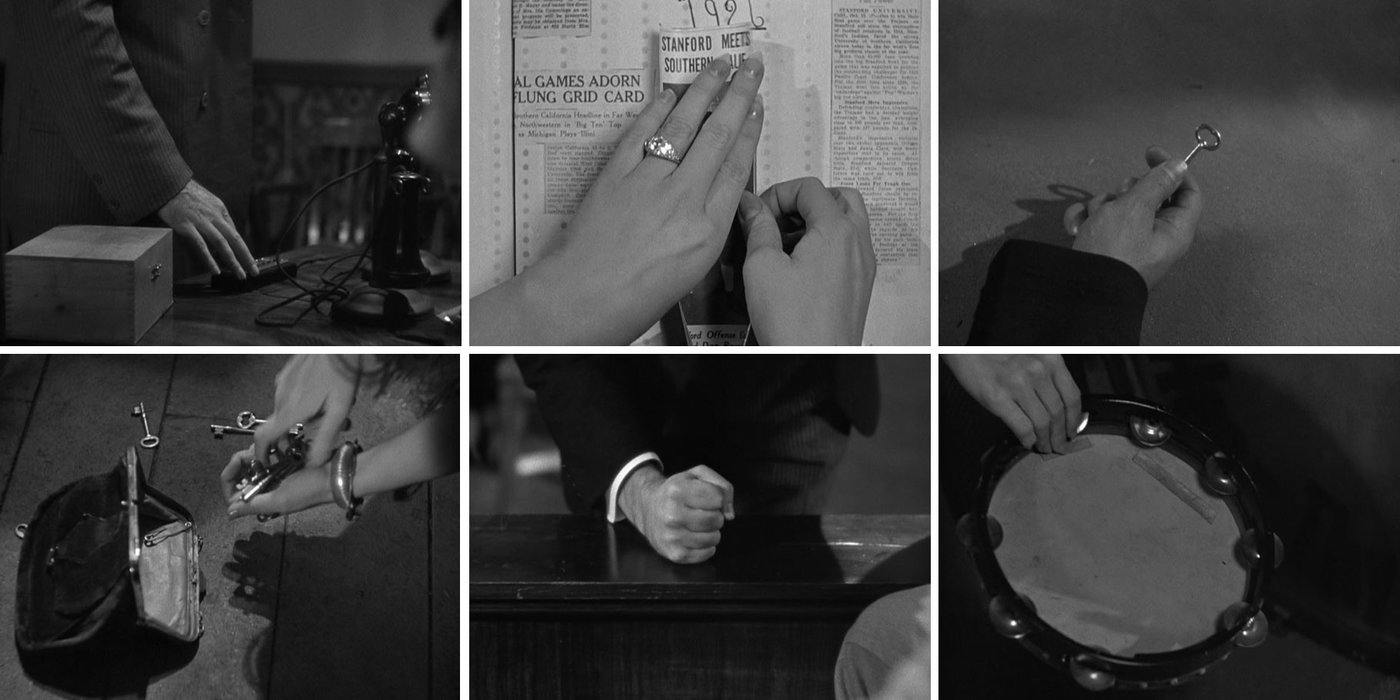

The image functions as an eyeline match and marks our point of entry into Jenny’s subjectivity, but the gesture itself is significant. This essay isn’t the place to rehash all that’s been written about Bresson’s hand fetish, but I would argue that Wellman’s systematic insertion of such shots, which is uncharacteristic of his other work from the era, moves beyond simple storytelling and symbolism (although it is also that) and approaches the radical style Francois Truffaut describes in his review of A Man Escaped:

What this amounts to is that Bresson has pulverized classic cutting—where a shot of someone looking at something is valid only in relation to the next shot showing what he is looking at—a form of cutting that made cinema a dramatic art, a kind of photographed theater. Bresson explodes all that and, if in Un condamné the closeups of hands and objects nonetheless lead to closeups of the face, the succession is no longer ordered in terms of stage dramaturgy. It is in the service of a preestablished harmony of subtle relations among visual and aural elements. Each shot of hands or of a look is autonomous.

Frisco Jenny is in many respects a typical Hollywood production of the early-1930s. Most of the cutting is classic dramaturgy, so I don’t wish to imply that Wellman influenced or even anticipated Bresson’s mature style. However, the film does work on that rare, unnerving plane where the most talented of Dostoevsky’s descendants play. I’d begun to think of Jenny as a compatriot of Fontaine (A Man Escaped) and Michel (Pickpocket), not to mention any number of Dardenne protagonists—one more condemned soul in need of redemption—even before I’d consciously noted all of the hands.

I’d be hard pressed to make the case for each of these images achieving the kind of autonomy that Truffaut praises in Bresson’s montage. Frankly, two of these inserts are punchlines. However, the shots of hands and the string of subjective portraits of Jenny combine to gradually, imperceptibly, accumulate emotional freight until being unloaded in the final moments of the film. Regarding the finale of Frisco Jenny, I would borrow again from Truffaut’s review, this time without reservations: “What is important is that the emotion, even if it is to be felt by only one viewer out of twenty, is rarer and purer and, as a result, far from altering the work’s nobility, it confers a grandeur on it that was not hinted at at the outset.”

Absence, loss, regret, love, and uncompromising sacrifice—ultimately, each small gesture and silent expression enacts Jenny’s tragedy, but it’s only after she’s chosen to face the gallows that the gestures are imbued, retroactively, with such grandeur. For example, much earlier in the film, Jenny goes into labor while holed up deep in post-quake Chinatown. The preacher fetches a doctor and leads him through a labyrinth of dark alleyways until they find the right door and knock. (The staging of the scene reminds me of Pedro Costa’s Ossos, another contemplative, Bressonian film involving a baby!) Wellman elides the birth completely and cuts, instead, to a medium close-up of the preacher blessing the child. It’s a sincere moment, with none of the irony that characterizes so much of Midnight Mary. The camera then pulls back through the rubble, watching from a distance as Jenny’s faithful servant Amah carries the baby to her. Jenny reaches for him, and his small hand finds her finger, their first touch.

The sequence is a small marvel and features Wellman’s trademark tracking shots and two frisson-causing cuts (from the dark hallway to the praying preacher; from the long shot of the dark room to the relatively bright medium close-up of Jenny and the baby). On a first viewing, the sequence signals a shift in the film’s style and ambition. Frisco Jenny suddenly blossoms into something more melodramatic (in the best tradition of the word) and sublime. On a second viewing, it’s devastating, as it anticipates the film’s precise denouement, Jenny’s final contact with her son.

In the closing moments of Frisco Jenny, Steve threatens to expose the connection between District Attorney Dan Reynolds and his real mother. Left with no other recourse and desperate to protect her son’s reputation, Jenny kills Steve and begs Amah to preserve their secret. As she awaits execution, Jenny is visited in prison first by Amah and then by Dan, who has been troubled by her case for reasons he can’t quite understand. The dialog is serviceable: he offers to stay Jenny’s punishment if she confesses her motives; she quietly refuses. However, Wellman’s mise en scène and Chatterton’s performance elevate the scene to a work of high art and transform Jenny into one more cinematic saint.

These icon-like portraits from Wellman, Carl Dreyer, Jean-Luc Godard, Andrei Tarkovsky, Robert Bresson, and John Cassavetes are, I think, true objects of contemplation—staggering but glamourless images that invite sympathy, compassion, and deep curiosity while steadfastly resisting interpretation. To borrow a line from Nathaniel Dorsky, they are “manifestations of the ineffable.”

When Jenny and Dan speak for the last time, she’s reclining on her prison bunk, leaning away from him. However, because she’s now staged on the left side of the frame (this is an especially good example of the precision of Wellman’s style paying emotional dividends), the momentum of the image pushes them toward each other, figuratively speaking, despite her best efforts.

It’s a rare instance in the film when Jenny is allowed the position of sympathy and authority in a shot/reverse-shot breakdown, and because we have spent the previous hour experiencing this world through her, the chaos and discord of her emotional state are palpable. When Jenny quips about Dan working hard to undo a case he’d just won, he replies, “In court I was sure. Now I’m not. Help me,” and on “help me” Wellman cuts back to Jenny and dollies in to a close-up. However, because he waits to pull focus until the camera has stopped moving, she is left blurry in the interim.

It’s subjective filmmaking taken to a logical and vivid extreme. The dolly-in last six seconds, the amount of time it might take Jenny to process her son’s cry for help, relive that first touch in Chinatown, indulge the fantasy of embracing him and confessing, choke back her tears, regain her composure, and claim her fate. “Never,” she whispers, as the camera snaps back into focus. Dan stands to say goodbye and places his hand on her shoulder, and she, impulsively and with much grace, presses it against her cheek and kisses it. Absence, loss, regret, love, and uncompromising sacrifice—Jenny’s tragedy climaxes with this, her final gesture.