Dir. by Jonathan Caouette

The theater where I saw Tarnation subjects early arrivals to “The Twenty,” an obnoxious barrage of advertisements that I tolerate for two reasons: first, because it helps to subsidize Knoxville’s only venue for foreign and independent cinema (and given the small crowds that typically greet me there, it would appear that those subsidies are essential); and, second, because I relish the moment immediately following “The Twenty.” The digital projector is quieted, the house lights dim, and the film projector comes to life. In those few seconds of silence before the first trailer begins, you can hear actual film spooling through a gate—a mechanical process with gears and a bulb and celluloid.

I mention all that because when the projector kicked into motion yesterday, I wondered how much longer the sound would last. Jonathan Caouette, as we all know by now, constructed Tarnation on his Mac for a couple hundred bucks. It’s composed largely of still photos and home videos. Little film was exposed in the making of his movie, and the quality of its presentation would have suffered little had it been projected digitally. As most films will be. Soon enough. That’s what was I thinking, at least, as trailers for Kinsey and The Sea Inside streamed by. Two biopics of extraordinary men who led extraordinary lives. Two films I haven’t the slightest interest in seeing. I’m just not interested in extraordinary lives, apparently. Give me the ordinary. The mundane. But present them to me with a touch a grace, and do it honestly and artfully. That’s what I was thinking, at least, when the ads finally ended and Tarnation finally began—in darkness and to the diegetic rumblings of Caouette’s camera.

A quick synopsis. When she was twelve years old, Renee LeBlanc, a strikingly beautiful child, fell from the roof of her home and suffered temporary paralysis. Her parents, convinced that Renee’s troubles were psychological, approved aggressive treatment, and over the next two years she was subjected to more than two hundred rounds of shock therapy. Whether her mental illness existed prior to the treatments or was, in fact, a result of them Tarnation does not make clear (and cannot make clear, given the vagaries of memory and denial). Caouette, Renee’s only child, suspects the latter, however, and his film is a blinding, visceral document of the anger, sorrow, desire, and hope (despite it all) that have forever colored his perceptions of art, family, and love.

Drawn from nearly 160 hours of home movies, tape recordings, and clips from Caouette’s amateur narrative films, and complimented by odes to pop culture and by an aggressive soundtrack, Tarnation has been described by its executive producers Gus Van Sant and John Cameron Mitchell as a “movie of the home” and an “autobiographical documentary.” In the case of Tarnation, classification is no exercise in pedantry, for evaluating its success or its artfulness (for lack of better words) demands discussion of its aims and methods. The film is compelling, to be sure—always interesting and, at times, deeply moving. Only the most jaded could emerge from the experience of Tarnation without respect for its subjects, a mother and son who have somehow managed to emerge from the circumstances of their lives with a hard-fought love for one another and for the sacred moments of beauty in life. It’s worth seeing for that reason alone.

But, finally, I think, the film’s formal problems—its haphazard construction, conflicted voice, and questionable representations of life—become too great to sustain the weight of Caouette’s noble ambitions. (Because this is a blog and not a formal essay, and because I really should be working on other projects, I’m going to make it easier for myself by tackling each of these critiques in turn. The best compliment I can give Tarnation is to say that it’s the first film I’ve seen in weeks that compelled me to write.)

Construction. The first of my complaints with Tarnation is also perhaps the most petty, and it’s simply this: After the opening titles, I don’t recall a single moment of silence. The film moves from one montage to the next, each accompanied by music culled from Caouette’s personal collection of CDs and LPs. Occasionally the songs are manipulated for effect—tailored to enhance the images on screen—but much more frequently, the picture is cut to sound. Caouette’s much-discussed exploitation of iMovie’s editing features explodes his home movies into stunningly beautiful abstraction, but they find their rhythms too easily in the music. This, it seems to me, creates an aesthetic dissonance. I could too clearly imagine the filmmaker, exhausted by the endless decisions of editing, pulling an album from his shelf and allowing the song to determine the cuts. “Rhymed abstraction” (or some such makeshift term) might be employed to justify the technique. Perhaps it’s a fitting description of schizophrenia. I don’t know. I just felt that the form too often co-opted the content, which is most regrettable because when Tarnation does find its voice, it’s stunning. Which leads me to . . .

Voice. Following a trip to visit his mother, the teenaged Jonathan smoked two joints that he later learned had been laced with PCP and dipped in formaldehyde. The resulting psychotic episode left him with depersonalization disorder, “a feeling of disconnection from the body and a constant sense of unreality.” Caouette writes:

They don’t really have a cure for this disorder, so it’s something I have learned to live with. Tarnation is designed to mimic my thought processes so the audience can also feel like they’re in a living dream, which can be scary and intense, but also beautiful and glorious. Tarnation is a documentary in the sense that it’s a true story but it’s also a happening, an encounter, and a way for you to meet me and for me to meet you.

Caouette mimics his thought processes through formal means, beginning with the narration, which is textual, rather than the expected voice-over, and which refers in the third person to the Jonathan we meet on screen. This is a Jonathan Caouette, the film implies, one of many that we will eventually meet. There is the young Jonathan with his first camera, acting the role of an abused woman “givin’ testimony” to her sins. There is the teenaged Jonathan, openly gay and directing his musical adaptation of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (brilliant!). There is the 20-something Jonathan, living (happily?) and acting in New York City. We are asked, in a sense, to read each of these personae as characters in a film about a boy’s search for the love of his mother. It’s all happening to them, the film implies, to those people.

But the step into third person is a conceit, and, in my opinion, it’s an unnecessary and misguided one. In the final act of Tarnation, when Caouette is living in a long-term relationship and is choosing to take on the responsibility of caring for his mother, we meet the Jonathan whose voice has been, by turns, whispering, screaming, and crying in our ears. Caouette’s effort to dramatize the “disconnection from his body” is a posture: Tarnation is no less self-aware than one of Caveh Zahedi’s autobiographical films and it lacks Zahedi’s formal rigor. I like the idea of a film such as this deliberately fracturing the narrative voice, but the execution in this case is poor. A symptom of Caouette’s relative inexperience, I would guess. Which leads me to . . .

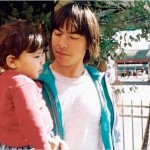

Representing a Life. Look closely at the image I’ve posted above. Mother and son. Finally at rest. Finally at peace. It’s one of Tarnation‘s closing images and also one of its most poignant. A glimmer of hope. Love among the ruins. But here’s the thing: the scene is staged. Renee is, as far as we know, really asleep, but Jonathan is not. He and David (Jonathan’s boyfriend) found her there on the couch and apparently couldn’t resist the precious, pieta-like beauty of the moment. The film begins with a similar trick: the camera is fixed on television static when David returns home to their apartment and wakes Caouette from a nightmare. He’s been dreaming about Renee, we are told. He’s worried. Cut to the next morning. Jonathan and David wake to the sound of an alarm clock. Try to ignore the tripod. Try to ignore the fact that you’re now suddenly watching a narrative film.

I was anticipating Tarnation with some excitement because I had assumed that, unlike the larger-budget biopics filling the multiplexes right now, it would, without compromise, elevate truth above affect. But it does feel compromised. Caouette betrays the integrity of his film by focusing again and again on images that seem to float outside of the film as aesthetic objects. Like his mother, Caouette is a striking beauty (as is David, actually), and portions of the film play like a love song to their remarkable faces. (Notice the slow zoom-ins on Jonathan’s and David’s dark eyes.) Perhaps it’s another symptom of depersonalization disorder to reduce people to two-dimensional characters, but, regardless, it doesn’t make for great filmmaking. Ultimately, Tarnation is a compelling film about extraordinary people who have lived extraordinary lives, and that, regrettably, is its greatest asset.