Dir. by Jonathan Glazer

The first image in Jonathan Glazer’s Birth is a nearly two-minute, uninterrupted high-angle shot of a jogger making his way through snow-covered Central Park. The camera follows a few steps behind him, floating dreamily twenty or thirty feet over his head. It trails the runner for several hundred meters, over hills, around bends, and, finally, under a quiet overpass before momentarily losing sight of him in the darkness. The first cut is to the opening title: Birth, rendered in an ornate, story-book script.

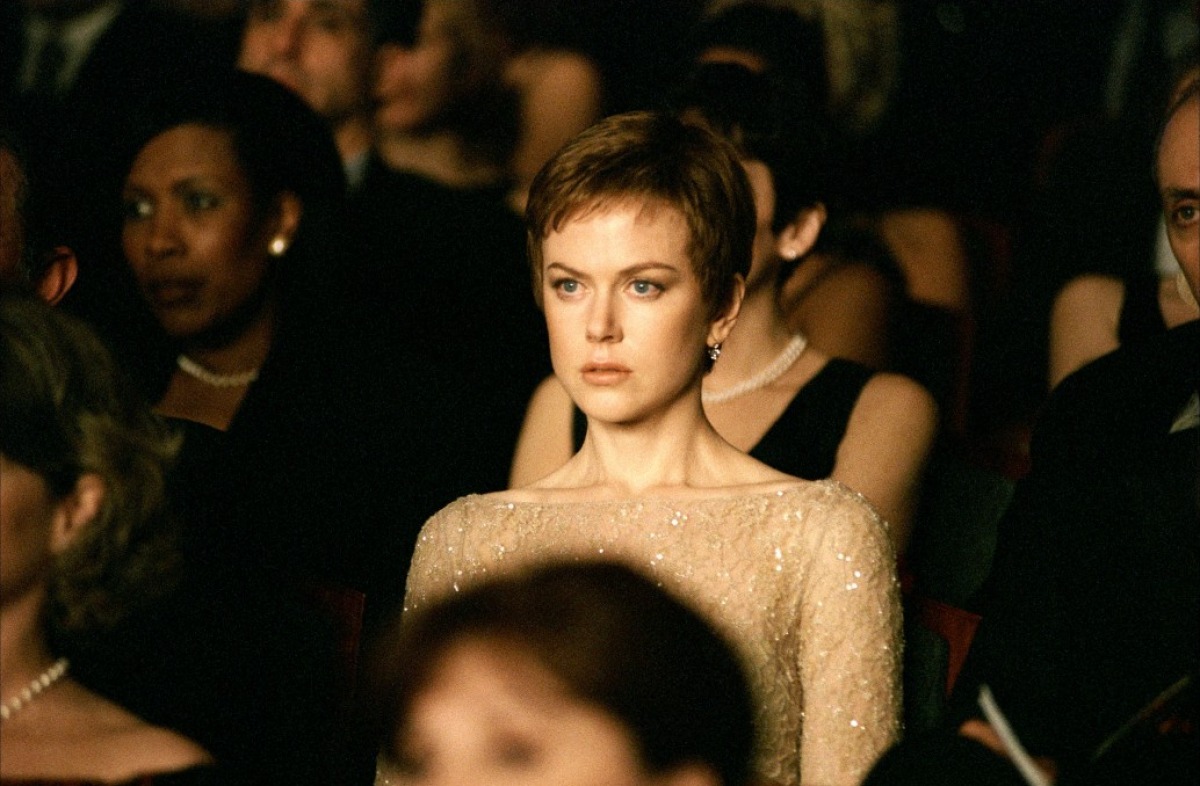

Like most film viewers, apparently, I paid little attention to Birth during its theatrical run. What I remember of its marketing campaign cast the film as another Nicole Kidman prestige picture, one of the countless many that have appeared, with assembly line-like regularity, in recent years. My expectations, though, were completely undone by that first shot. While watching Birth‘s opening sequence I was struck by a feeling I’ve experienced again and again in the months since, as I’ve caught up with Glazer’s first feature film, Sexy Beast, and with his many television advertisements and music videos: I was watching a filmmaker whose mise-en-scene was purposeful, controlled, surprising, and stylized (in the sense that “stylized” is now commonly used to describe films by Quentin Tarrantino and Wes Anderson, for example) but always in the service of story and character. I trusted Glazer immediately and completely.

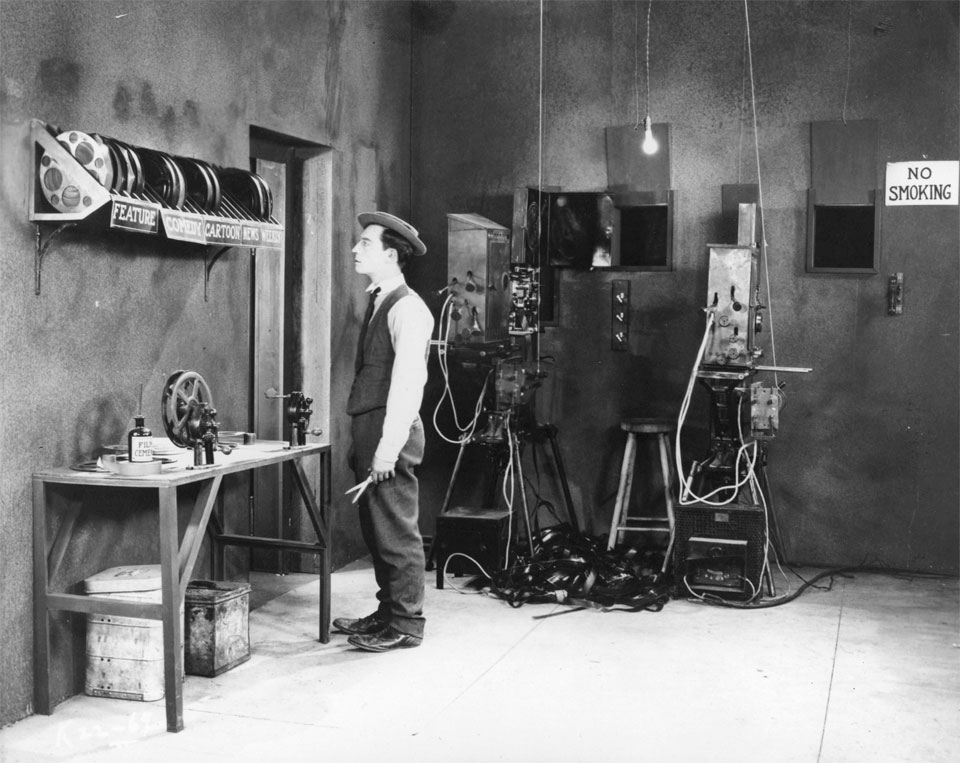

I’m harping on this one shot because, having now seen Birth three or four times, and having watched the opening moments of the film more times still, I’m fascinated by the durability of its effect. The high angle perspective makes the jogger a small, dark (he’s dressed in all black), and indefinable mark against the white snow. It’s barely color photography at all, in fact — the palette is all shades of gray and beige. This, combined with Alexandre Desplat’s “Prelude,” puts us in a world that isn’t quite real. It’s more Chris Van Allsburg than Martin Scorsese. Central Park is recast as the Grimm Brothers’ forest; I wouldn’t be surprised at all to find the Billy Goats’ troll or a Frog Prince hiding in the shadows beneath that bridge.

Like all good fairy tales, Birth is a dreamscape, really. Fantasy and suppressed desire are manifest in symbol-heavy ghosts and magic. Reason surrenders its claims to knowledge. Emotion reigns. The two films I think of most often when watching Birth are Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut and David Cronenberg’s The Brood, both sublime and uncanny horror stories in their own right. Glazer’s debt to Kubrick is all over Birth — from the slow tracking shots and symmetrical compositions to the spanking scene, which is lifted, whole hog, from Barry Lyndon — but it’s their shared interest in the psychology of sex, death, and human subjectivity that links Glazer’s film most closely with that other Kidman-as-impossibly-wealthy-Manhattanite movie.

Birth is, I think, a curious reimagining of the ideas that propel The Brood, the 1979 splatterfest in which an experimental form of self-actualization therapy gives birth, quite literally, to the anger and self-hatred that, until that point, had been safely repressed by each analysand’s super-ego. Always part satirist, Cronenberg treats 1970s psychotherapy with suspicion (if not downright contempt), but, as has become his trademark, the real horror of The Brood is his qrotesque rendering of deep-seated human anxiety — and, more specifically, anxiety about death, bound as it is to the corporeal, “flesh”-iness of our always-decaying bodies. (Forgive me if that all sounds obnoxiously pedantic. This notorious image from The Brood is more to-the-point.)

The basic premise of Birth is simple enough: a decade after her husband’s death, a young woman meets a ten-year-old who claims to be his reincarnation. Although the boy is certainly a more rounded character than the knife-wielding homunculi of The Brood, he shares their function as a materialization of repressed trauma. (He doesn’t just serve this function, of course. It’s to the film’s credit that, while remaining largely within Anna’s subjectivity — at least from that amazing opera scene on — Glazer and his cowriters have built nice parallels into the story in order to emphasize the similarities between Anna and the young Sean. Their visits to Clara and Clifford’s apartment is one good example.)

Entering spoilers territory . . .

That the central mystery of Birth — is the boy her dead husband or isn’t he? — can be explained away by an important plot point is, impressively, both utterly beside the point and exactly what makes the entire premise of the film so damn interesting. Had Birth ended without revealing the dead Sean’s betrayal of Anna — had the mystery simply been left unresolved or resigned to the realm of the supernatural — Glazer’s portrait of mourning and grief would have been no less impressive or terrifying. (It likely would have become even more dreamlike, veering closer to the territory of a film like Jean-Paul Civeyrac’s À travers la forêt.) As it is, the secret ultimately remains hidden from Anna, so her character, at least when viewed from within the film’s world, is unaffected by any alterations to this particular plot point. Or think of it this way: Kidman would perform Anna exactly the same way, regardless of whether or not those letters existed.

But the letters do exist. And although we never get a significant peek into them, we can make certain safe assumptions about their contents. They’re written by a woman desperately in love with her husband. They touch on the mundane details of the couple’s domestic life together. (“This is my desk. This is where I worked.”) They’re frank enough and intimate enough to include details about a secret romp on their brother-in-law’s couch. They express her regret over the amount of time they are forced to spend apart and her desire to be with him more often. (I wonder, even, if the very act of writing those letters could be a sublimation of Anna’s insecurities and suspicions about Sean’s fidelity.)

I’ve always read Eyes Wide Shut as a hopeless attempt by a man to regain the fictional unity of his own identity after having it exploded by a wife who, as is always the case, turns out to be not at all the woman he had imagined her to be. Birth, I think, is essentially the same story. By way of comparison to another “trick” film, at the end of Birth the “real” Sean remains as much a mystery to us as Keyser Soze. Anna so quickly and so easily falls in love with the young Sean not because he’s a manifestation of her dead husband but because he so effortlessly performs a role that is wholly the work of Anna’s imagination. She has conjured an idealized version of Sean through the magical incantation of her love letters. “I can’t be him because I’m in love with Anna,” the boy tells a police officer, adrift in his own impressive whirl of identity confusion.

My only complaint with Birth is its relatively clunky ending. The final image of Anna wailing in the surf is like a mash-up of The Awakening and The 400 Blows but without the inevitability or rightness of either. I wish it ended, instead, like Eyes Wide Shut, at the precise moment when all the horrors exposed in the film are once again safely repressed by a single word. In Kubrick’s film, the tension is superficially resolved in a toy shop, where Alice restores Bill’s sense of himself by simply telling him they should “fuck.” In Birth, Anna and her future husband negotiate in a corporate boardroom, where she surrenders all of her desires to more acceptable cultural norms. “I want to have a good life, and I want to be happy,” she says. “That’s all I want. Peace.”

I wish the film ended here. “Okay,” he says. Cut to black. And like magic, the monsters disappear.