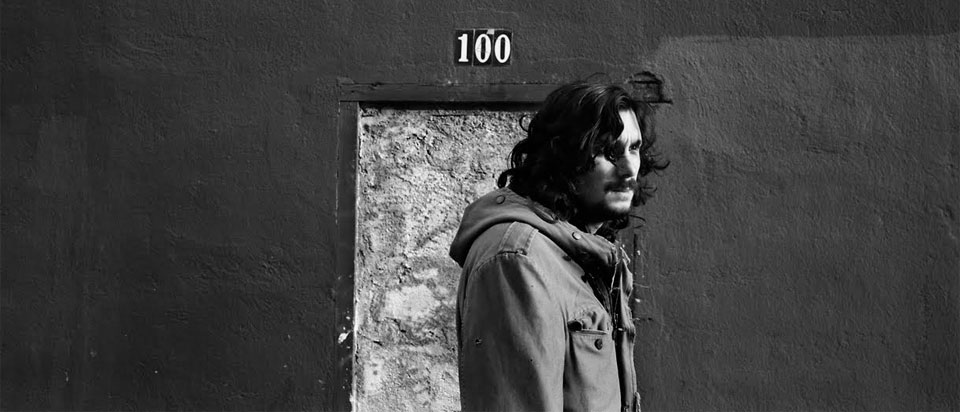

This conversation was originally published on tobecontd.com, an interesting site that invited pairs of writers to tackle a single subject over the span of a month. Michael Leary and I have been discussing Claire Denis via film forums, discussion groups, and private emails since the early 2000s, so we used tobecontd.com as an excuse to finally talk face-to-face. This is a heavily edited version of that two-night, four-hour conversation.

The piece ends with my interview with Claire Denis, in which she addresses many of the issues that Michael and I raise.

1. Ways of Looking

DARREN HUGHES: Where should we begin?

MICHAEL LEARY: The vast majority of writing and conversation about the films of Claire Denis is inspired by post-colonial theory, strains of social memory theory, and the sexual or racial politics of the body in cinema. These bits and pieces of commentary exist in a kind of theoretical constellation around her work, which has become a standardized or even canonized reading of what is happening in her cinema. There is much value in thinking about Denis’s films from these perspectives. But I do not want to limit ourselves to these traditional perspectives here, because I think those conversations have missed a lot of formal and expressive detail in her work.

For example, you have spent a lot of time writing about a feeling or experience of “sorrow” in Denis’s films—about these very deep emotions that become evident upon successive viewings. That aspect of Denis gets lost very quickly in critical conversation, and I think it’s one of the most interesting aspects of her work—that it’s so affective.

So, to answer your question, I think a good place to start is to try to figure out where that affectiveness comes from.

HUGHES: When we first began exchanging emails about this little project, I pitched a simple structure: “Looking at people, places, and things.” Are you still okay with that?

LEARY: Yes, because that is how Denis seems to think throughout her creative process. When she talks about her screenwriting and her filmmaking in interviews, she does not really talk about movie ideas or motifs at all, and she does not often talk about a pat theoretical rationale for using the camera this way or that way. She always talks about the people that she’s thinking about in particular places and engaging particular objects.

So perhaps a simple construct like “looking” is a handy place to start. It’s the one word that seems to express her method best. I tend to be pedantic about defining theoretical ideas in this context, but given your admiration for her films, I’m curious to know what “looking” as a concept or filmmaking activity entails to you.

HUGHES: At the most basic level it’s a shorthand for form, in the same sense that if we were talking about an novelist we’d be discussing language, metaphor, structure, and so on. If I boil down what I love about her films, it’s the way she sees the world. It’s very consistent, unique, and, as you said, deeply affecting.

Increasingly in recent years, my most comfortable approach to criticism has been an effort to describe as best as I can how a film is constructed—going back to formal analysis with a kind of pedagogical ambition. I do it almost selfishly. My standard line on Bastards (2013), for example, is that the first viewing was deeply disturbing and horrifying; the second was sorrowful. When I trust a director, I know that hasn’t happened coincidentally. There’s a voice guiding my experience of this world that I’m entering into for 90 minutes. I want to understand, as best as I can, how that happens.

What I’ve found, though, is that regardless of the path, I almost always end up back in the same place. A formal analysis of Denis will almost certainly land in that same theoretical constellation you mentioned. Beginning with “looking” is my shorthand way of suggesting that we start by figuring out what she’s doing with her camera. I’m confident the other stuff will come. I don’t have to force a discussion of post-colonialism onto Denis’s films. That’s going to happen, inevitably.

LEARY: Ricouer talks about using critical theory to achieve a second naiveté, wherein we filter the text or the cultural artifact in question through various theoretical mechanisms with the intent of being able to see it again as if for the first time. Denis’s films short-circuit that process. As you just stated it, whether you filter it through some theoretical construct or come at it from a purely formal analysis, you end up at the same place. I think you laid your finger on precisely what intrigues me about her filmmaking the most: that there’s a certain irreducible complexity to it. Her expressions accomplish so many things at the same time, and are therefore either resistant to or open to critical description in a special way. I do not say this to argue that Denis is impervious to criticism or that her films are not open to standard critical analysis; rather, critical lenses are not immediately necessary to identify with what she’s doing.

Writing in Retrospect

HUGHES: One thing I found surprising about sitting down with her films over the past two weeks and watching them all again is that some of the films didn’t work for me—or not in the same way I expected them to, or in the same way they worked a decade ago. I feel like I have a better sense of what I love about her films and that I’m able, finally, to talk about them with some objectivity.

LEARY: Let’s do an experiment then. How about we trade scenes that we think are significant for triggering an understanding of what Denis is all about and thinking through those together formally?

HUGHES: It’s an obvious place to start, but the opening shot of Chocolat (1988) is a pretty great illustration of several aspects of her work. The film opens on a black man and a young black boy swimming in the ocean. It’s a static, long-duration shot that allows viewers to just sit with the image for a while, to develop preconceptions, to imagine and reimagine what we’re looking at. Then the camera slowly pans 180 degrees and we see France (Mireille Perrier), a 20-something white woman sitting on the beach.

That pan, from a fixed tripod, is very atypical. Relative to the rest of her films, Chocolat seems almost classical. There are scenes where you can practically see actors hitting marks, which is unthinkable in Denis’s mature work. But the pan is very much typical in defining the perspective of her films. It’s essentially an eyeline match in reverse. Instead of seeing the person look, followed by an insert of what they’re looking at, we’re presented with an image and are allowed to interpret it ourselves, only to have that interpretation undone by the filmmaker, who steps in to say, “Wait. You’re not looking at this idyllic moment; she is looking at it.” It’s a complicated move because it forces us to resituate ourselves in the scene and to reconsider those preconceptions.

I remember being surprised, after I saw Chocolat for the first time, to read a review that described the framing device as unnecessary. Denis drops us into the perspective of a white European woman who is interpreting images of Africa, and every other frame of the film is that process unfolding in front of us. The perspective becomes even more complicated as it’s warped by memory. I’d never noticed until this viewing, for example, that Protée (Isaach De Bankolé) says to the young France, “Here’s your seed, my little chickadee,” and then much later in the film, the stranded plantation owner says the same thing to the African woman he keeps as his servant (or concubine or whatever she is). That second scene happens behind closed doors, so the young France couldn’t have witnessed it. Instead, it’s a moment the adult France is, in essence, writing in retrospect. The same thing happens when she remembers Protée teaching her the names of her eyes, ears, and mouth, which is a scene she witnesses between the father and son in the framing story.

All of this leads directly to what we see in so much of Denis’s later work: the erasure of clear lines of demarcation between the real, observable world and the more surreal world of dreams, memories, and subjective experience.

LEARY: The majority of the film is almost an afterthought to the initial formal flourish of the camera you described so well. Another complication of that opening scene of Chocolat is that we hear the ocean and the wind as part of the aural landscape of that sequence, but when we pan back around to France, she has headphones on. So there’s this added dimension of us being exposed to a natural world that she herself is a bit removed from. It’s not totally subjective to France at that point—but to us.

HUGHES: That’s great. I’ve seen Chocolat a half-dozen times over the years and can clearly picture France removing the headphones, but I’d never made that connection. The film’s recurring non-diegetic music makes its first appearance as the flashback scenes begin, so I’m going to assume from now on that we’re hearing the music France had on her Walkman!

Networks of Subjectivities

LEARY: I’m quite fond of U.S. Go Home (1994), and there’s a scene near the end that seems programmatic for Denis. It’s surprisingly abstract, considering the film was originally developed for TV. After the kids leave the party and Captain Brown (Vincent Gallo) picks up Martine (Alice Houri), they’re driving down the road together and wild horns of “Al Capone” by Prince Buster are playing on the radio. As he drives, Brown is also checking out Martine whenever he gets a chance. The camera is positioned behind them, which allows Denis to switch points of view so that we watch Brown looking at Martine, and then we watch Martine looking at Brown. Meanwhile we see movement through the windshield as the car progresses forward through the night.

You can practically hear their thoughts. As a young girl, Martine is anticipating her first experience of sex; she’s nervous, wondering what’s going to happen. You can feel the tension between their ages. Brown is basically a crass foreigner. He seems experienced; she is obviously not. These differences are part of the enormous suspense present in just watching them look at each other. Then, the camera tilts up into the trees, which stream by, depositing us in the nocturnal abandon of the moment and a feeling of Martine’s passage into something.

After looking up into the trees for a full minute or so, the film eventually cuts to a static shot of the car, which is parked, and Brown and Martine go off into the woods together. You don’t get the impression that this is very pleasant or romantic for Martine, but as the sequence continues and they get back into the car, she leans over and lays her head on Brown’s thigh as he drives.

The elements of that scene are so rudimentary. They’re looking at each other. The camera pans up into the trees. It’s a microcosm of everything Denis does. We think of her as a very subjective filmmaker, and at times her eyeline matches connect us with a given character’s perspective, but her compositions often get a bit trickier. In this sequence we’re forced to alternate between the gaze of Brown and Martine, to identify with them, but then she pulls us away into some entirely other, meditative gaze. We experience a network of subjectivities in that brief episode, all of it training us to properly perceive its culmination as a moment of very complex emotion: Martine resting against Brown’s thigh.

HUGHES: With his hand stroking her hair. Denis loves hands.

Two things. First, I’m glad you mentioned that shot of the trees. Having seen Bastards fairly recently before beginning this little Denis retro, I noticed that shot in U.S. Go Home too because it recalls the drives through the woods in the later film. And once I became conscious of it, I spotted that shot in nearly every film—the creation of abstraction through quick movement. It’s a consistent technique for her, a way of bringing a kinetic energy to the visual field. The campfire scene in Beau Travail (1999), for example, when the men’s heads are shaking, or that shot in Vers Mathilde (2005) of the dancers’ legs and ankles moving quickly in a circle, or even the image of the dog chasing the camera in The Intruder (2004).

The scene you described is typical for Denis in that it can be interpreted symbolically, I guess—this is a rite of passage—but the viewer’s experience is much harder to explain because it’s approaching the avant-garde. It’s symbolic but also uncannily primal and a-rational.

You mentioned the complex network of subjectivities. I suppose Friday Night (2002) is limited to Laure’s subjectivity, and Bastards, Chocolat, and L’Intrus all see the world more or less through one character’s point of view, but in most of Denis’s films, subjectivity drifts—or is passed—between characters, occasionally landing also in some meditative or gods-eye view.

LEARY: It’s almost like there’s a current of electricity that passes when she swaps subjectivities.

The Wisdom of Denis’s Montage

HUGHES: I was surprised last week to find that L’Intrus doesn’t work as well as her other films. And I say “surprised” because it was seeing that film in 2004 that first sparked my obsession with Denis. I would describe L’Intrus as existing in some kind of subjectivity. We’re not objective observers of world, certainly. It drifts into surrealism or symbolic spaces, but is it even useful to call that film an experience of Louis Trebor’s (Michel Subor) subjectivity? In other words, I’m not even sure that subjectivity is always a useful framework for understanding her films. Maybe what I’m calling “subjectivity” is actually just a deep emotional intimacy that should be described with a different vocabulary altogether.

I suppose the ideal example of what I’m trying to get at is the dance scene in 35 Shots of Rum. Formally, it’s fairly standard filmmaking in the sense that everything is happening through eyeline matches. Of course, we get the added jolt of energy from seeing beautiful people dancing, shot by Agnes Godard, with a great song on the soundtrack, but the reason I smile like an idiot each time I watch that scene is because Denis is so clearly and so efficiently defining the relationships and histories and emotional longings between each of these characters.

LEARY: One element of the dance scene that has really struck me lately—I never noticed it before—is that after Lionel (Alex Descas) hands off Joséphine (Mati Diop) to her prospective suitor, he turns clockwise and then walks directly toward the camera. We actually see half of his head pass through the bottom-right corner of the frame. You very clearly see his eyes and an enigmatic smile on his face. That to me has become the anchor of the scene—his passage out, toward us, and down through the frame. It sets up the dance between the two children to whom he has granted his blessing.

HUGHES: When I interviewed Denis about 35 Shots of Rum, she described the film as a kind of tragedy, “in a family sense.”

LEARY: Tonight I was talking to my daughter and we had a Denis moment. She passed across my frame of vision and sat to my left as we set up a board game together. As I joined her she almost re-materialized there in this little domestic tableaux as individuated—her own person—by the way she has grown into herself over the years. These little moments happen as we watch our children age, but this time I instinctively paired it with the dance in 35 Shots of Rum.

That sequence works so well as a father and daughter scene because Denis’s staging of it is so visceral. When Lionel exits, it’s like a current has been cut. You can feel it. And his daughter has been left in the frame, now fully grown and independent. After the dance, when Joséphine sits in the chair and Noé (Grégoire Colin) sits in the booth beside her, the look on her face gives me the impression that she felt it too. It confuses her. She feels this invariable sorrow, but what else is she supposed to feel? Every component of that scene is just perfect.

HUGHES: And the next one is almost as good. Lionel doesn’t come home that night, but when he returns the next morning he’s walking down the street and he spots Joséphine leaning out of the window, cleaning. It’s a traditional eyeline match: a medium close-up of Descas looking up followed by a reverse angle to the window. What’s somewhat atypical for Denis is that she cuts back to Descas and gives us a reaction shot, and we sense immediately that he knows what he’s coming home to. He doesn’t know yet that Noé is leaving or that Joséphine has been looking at old family photos, including a quick shot of her dead mother, but he knows that his daughter cleans when she’s upset, and it’s all captured in that quick, three-shot sequence. This might be too strong a word, but I think there’s a wisdom in that montage.

LEARY: Another way of coming at that very intriguing concept of wisdom as a principle of Denis—and I say this especially after watching Vers Mathilde recently—may be to say that Denis does not think about relationships so much as configurations.

In 35 Shots of Rum, the configuration of these people is very precariously balanced, and the film is about the dissolution of that comfortable configuration. You can feel it viscerally because she focuses on the material or physical form of the configuration as it exists, making its dissolution in an actual dance so striking. When Lionel is walking home you can now feel everything out of balance, the pieces don’t fit together anymore. And that is painful. When we have close friends move or our social circles are shifting, we feel that the configurations we have become wedded to are unraveling. Denis seems to understand that not just as a common experience, but a basic impulse of the cinema.

2. Materiality and Abstraction

LEARY: We’ve been talking about different subjectivities and configurations in Denis’s films. Let’s talk about a very interesting, near mystical, wrinkle in the subjectivity of Beau Travail. At the end, we have Galoup’s (Denis Lavant) death scene, which transmutes into a sort of nightclub passage of ascension. In these final moments he dances with abandon to the “Rhythm of the Night,” quite literally shuffling off his mortal coil. It’s difficult to nail down the exact connection between the image of the final pulses of blood in his bicep and the cut to a softly lit dance floor. Formally, the connection is the beat, first of his pulse and then of the music.

But much earlier, there is a curious moment in which the legionnaires carry each other on their shoulders after partying in town, and Galoup seems to be narrating the scene from a distance. As the legionnaires round a corner, he appears in the same black shirt, black pants, and wingtips he’s wearing during the final nightclub dance. This is curious, because he left for the evening in his legionnaire’s uniform. His movements in this early morning light are also a bit out of character. They’re relaxed and dancerly. I interpret that as the ghostly intrusion of his character into the film’s past, which transforms all of Beau Travail in a deathbed recollection.

It’s a jarring image. I had never really noticed that before. Have you heard someone interpret his presence that way?

HUGHES: Not exactly, no. Like the headphones in the opening shot of Chocolat, which we discussed earlier, I can clearly picture Galoup in his two different outfits, but until you mentioned it just now, I’d never been conscious of the continuity/narrative questions it raises. I love discovering details like this!

Beau Travail opens with that amazing prelude: we hear orchestral music under the credits, then a snippet of a soldiers’ chorus before cutting to the legionnaires, who are dancing to pop music in a club. It all culminates with a montage of faces against a blue sky, scored by a snippet from Benjamin Britten’s “Billy Budd.” The men are looking at nothing in particular—they’re beautiful, uncanny portraits, really—until the final cut, from Sentain (Grégoire Colin) to Galoup. It reads as another reverse eyeline match and situates the film in Galoup’s subjectivity. The prelude is six or seven minutes long, I think, and ends with a low-angle shot of Galoup writing on a balcony. That’s when we first hear the voiceover. He’s already back in Marseilles, thinking back upon his experiences, almost in the same way that France (Mireille Perrier) is telling the story in Chocolat, or Maria (Isabelle Huppert) is remembering the previous few days in White Material. In fact, it wasn’t until tonight, when I was organizing some notes, that it occurred to me that all three Africa films use a similar framing device.

I’m so glad you mentioned the scene of the legionnaires carrying each other on their shoulders, because when I watched Beau Travail again last week, I jotted down, from cut to cut, what happens in that scene and then wrote, “Explain this montage!” I feel like that sequence is Denis’s Rosetta Stone. Forestier (Michel Subor) is riding in the back of a car at night, talking to the driver, when Galoup suddenly materializes in the light of the headlamps. Denis cuts immediately to a shot of Galoup’s girlfriend (if that’s the right word for her) dancing in a club, but the only sound we hear is a low-frequency drone. Then, suddenly, it’s daybreak and the legionnaires are walking silently through an alleyway, carrying first a black soldier and then Sentain. Galoup trails behind them—this is the part you described—and then Denis cuts back to the present in Marseilles, where Galoup is ironing his clothes. The white noise of the drone fades and is replaced by the sounds of the iron and a percolating coffee maker. (We could have another discussion just about Denis’s love of coffee makers and other home appliances.)

So, why does an intrusion of that kind of strangeness into Beau Travail work so well—it might be my favorite two minutes in any Denis film—whereas a more extended fantasia, or whatever we want to call The Intruder, seems ungrounded in some way?

LEARY: Is it a matter of balance or structure? Denis’s elements of abstraction work best when they’re embedded in—or materialize from—an existing dialogue or narrative sequence. The moment in U.S. Go Home we discussed earlier is a good example. There, like this final dance in Beau Travail, the abstraction is a form of passage or poetic movement.

Much criticism of The Intruder focused on its lack of any linear narrative throughput. It’s rife with what feel like subjective experiences of a narrative, but the actual storyline becomes so obscured in this process that each abstraction is disconnected from any semblance of a whole. In other films, her flights of abstraction work so well because they’re connected to narrative elements Denis has already spent time constructing. They feel earned.

HUGHES: I guess I want to make the next step in the critique. A few years ago I wrote a piece about To the Wonder (2012) that was an attempt to better understand my growing frustration with Terrence Malick. I ultimately settled on the idea that Malick’s montage was undermining the “thingness” of his subjects, that his images were being reduced too often to just symbols. I’m tempted to say the same thing about The Intruder. I should add that The Intruder includes many of my favorite Denis moments—the long shot of the purple sea, accompanied by Stuart Staples’s guitar loop, is sublime—but when I watch the film now I’m not able to turn off my rational processes: “the heart in the snow represents this, the shot of Sidney (Colin) holding his child represents that.” Whereas with Beau Travail—or even something like Nenette and Boni (1996), which is just as strange as Beau Travail in many ways—I’m content to chalk up the moments of abstraction as phenomenological experiences, as aesthetic sensation.

LEARY: I do like To The Wonder, but from that perspective, I agree that it is almost the Buzzfeed version of a Malick film. It quickly becomes an illustrated catalog of his filmmaking concerns rather than an organic emplotment of people and their configurations. The key difference is that I read the “thingness” of Malick’s images through a sacramental lens, whereas I don’t think Denis’s films permit or require that kind of theological rendering. Whatever happens after the suicide in Beau Travail is a good example. I’ve described it as a sort of ascension, for lack of a better term. The image actually lacks any of the religious or even spiritual undertones suggested by such a theological term. It’s a very material image, a suggestion of an existential release emerging from the very fabric of the film. Denis’s materiality has always led me to connect her more with Brakhage or Snow or Akerman than any of her other European counterparts.

Allowance and Subjectivity

LEARY: Another good example of the way Denis fits abstractions into her films are the little moments of surreal comedy dropped into Friday Night (2002). Friday Night was my first experience of Denis and is still, perhaps, my favorite of her films. I really connect to its riffs on genre, as there are nouvelle vague and noir elements present. There is at times even a Tati-like experience of Paris through the windows of the car and the impromptu democracy of its traffic jams. It’s easy to describe the film as Laure’s (Valérie Lemercier) subjective experience of this romance, but I think it’s a bit more complicated than that, as it’s more an invitation into this configuration of Laure and Jean (Vincent Lindon), which slowly develops as they grow more accustomed to one another. They rent a hotel room, they have dinner, and she wakes and looks for the car. In the final image, she skips down the street in a rare Denis moment of sheer joy.

What happens here is what you were trying to define earlier when you suggested we get away from the word subjectivity. We see the movement of letters across a license plate or sardines on a pizza because we’ve been given the gift of glimpsing Laure’s affection in the moment. Trapped in the car, she’s released from an impending sense of control she feels during the move to her boyfriend’s house. In the restaurant, her sense of abandon dances out into the frame in a material way. We’ve become reliant upon a few makeshift terms in this conversation, “allowance” and “configuration.” In Friday Night, we are “allowed” to be part of this “configuration” Denis constructs between Laure and Jean.

But let’s take Vers Mathilde as a clearer example. In this documentary she is inviting us to observe the way dancers configure themselves in the studio. This invitation is made through the camera—we get to be in there and among the dancers in close proximity and at great length. It makes me want to join them and feel what they’re feeling. What they’re doing together is inscrutable. It takes a while to get used to the odd lines and angles, but over time the jerks and wiggles and spins begin to feel meaningful. We flirt with the idea that these humans are conducting some kind of important work together. Their configurations begin to seem purposeful. And then it dawns on us that Vers Mathilde is, in fact, teaching us the natural grammar of the body.

HUGHES: I love how 90% of the film is exactly as you just described it. Then, in the last ten minutes of the film, the camera moves back to where the audience would normally sit. It’s a high-angle shot. We finally get to observe the dancers on stage from a more traditional point of view.

LEARY: When we pull back like that to a wide shot, my first thought was: This is just like watching people on the street. If you turn your head and glance at people doing everyday stuff, this is exactly what it looks like. Every day I walk from my office to someone else’s office. People are moving about, they’re picking up things, there are construction workers, people are making all kinds of movements in time and space. At first glimpse, the dancing in that last scene is like the flickers of all this movement I glance past in a routine way. But if you look more closely, their movements are really quite odd. And with Denis’s invitation to continue to look more and more closely, to start tracking with that oddity, we begin to feel that we’re witnessing something that is unexpectedly purposeful and beautiful.

Embarrassment and Invitation

HUGHES: The word that keeps coming to mind is “embarrassing.” I thought about it earlier when we were discussing the dance in 35 Shots of Rum. When Joséphine grabs Noé’s hand and leads him away from the dance floor, there’s that moment of electricity as you described it, but she’s also suddenly the little girl who was just kissed like a woman in front of her father. As a viewer, I consider it a privilege—and a deep pleasure—to experience that level of emotional intimacy in a film. It’s a kind of voyeurism, I suppose. There’s no shame in the exchange—it doesn’t feel pornographic, certainly—but being witness to a moment like that does make me feel a bit embarrassed for these strangers whose lives I’ve entered briefly.

LEARY: I think another way to frame that is in terms of a compassionate subjectivity. When Denis is interviewed, you hear much about the difference, or the différance—to use a very continental term—between her African background and her cosmopolitan Parisian experience. In her filmmaking, she at times claims the burden of the history of European colonialism, and that tension lends her a compassion that I don’t experience in many other filmmakers. If we have made any headway in better defining subjectivity in Denis, or the affectiveness of her cinema, I think it begins here in this emotional or existential tension that becomes embodied in the configurations of characters in her films. Her films really are all a sort of post-critical dance.

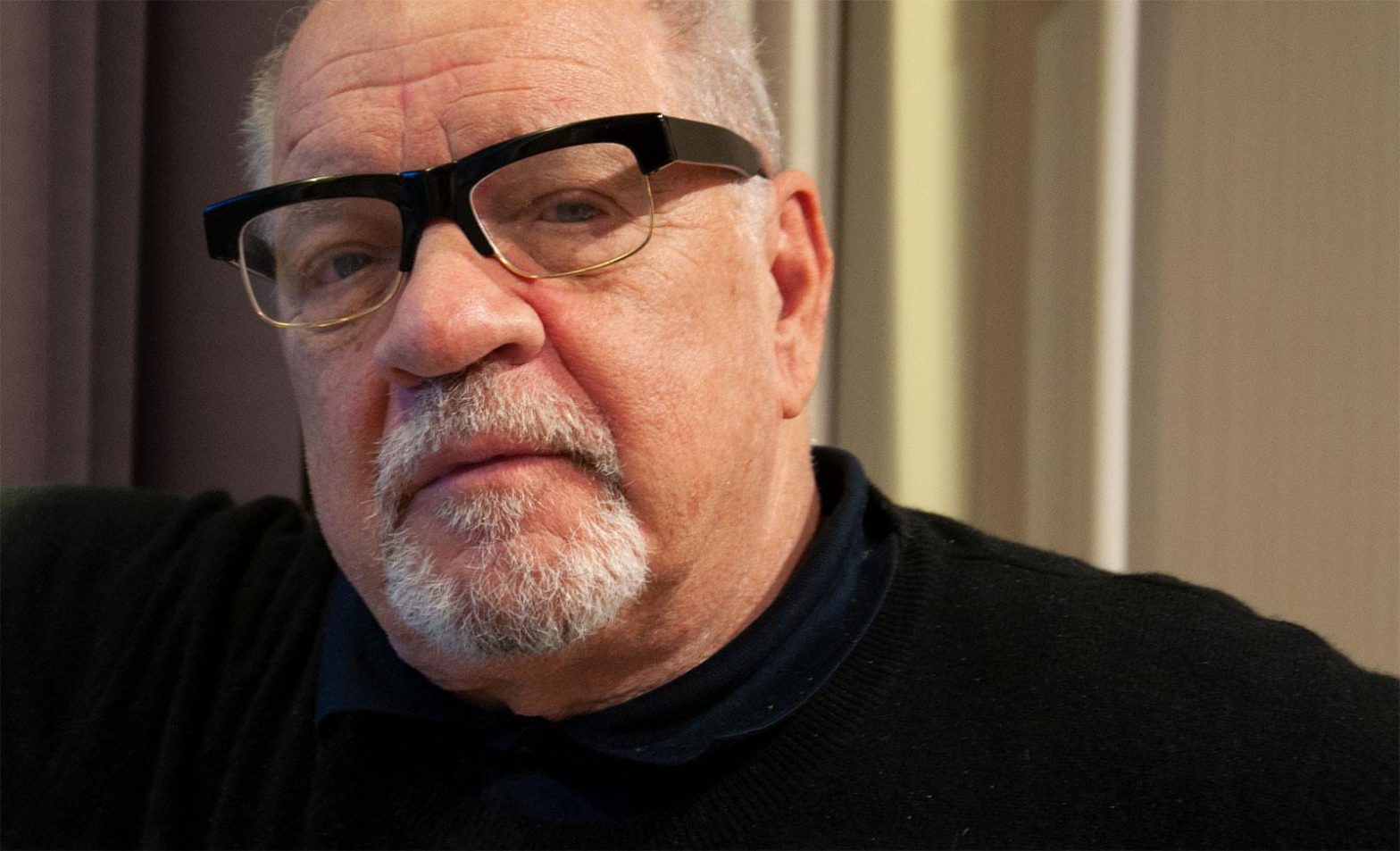

HUGHES: This project gave me an excuse to track down The Night Watchman (1990), Denis’s two-part documentary that’s essentially a conversation between Jacques Rivette and Serge Deney, with Denis herself also chiming in from time to time. This was the first time I’d ever seen Rivette speak at length, and I have to say, I was charmed by him. He’s very humble and self-effacing. In fact, the only time he gets especially animated is when he tells the story of visiting Paris decades earlier to see Robert Bresson’s original cut of Les dames du Bois de Boulogne(1945). Once a cinephile, always a cinephile!

There’s a wonderful moment in The Night Watchman when Daney describes curiosity as the “queen of virtues.” Rivette is wholly in agreement and basically says that if he lost his curiosity he would have to stop making films, which feeds into a larger discussion of Rivette’s moral contract with his actors. I’m fighting the urge to draw a direct correlation between Rivette’s style and Denis’, but I do think they share a particular and tender affection for the people who populate their films. Denis looks at the world with a deep curiosity even when that curiosity leads her to the ugliest parts of human nature. For example, after seeing Bastards five or six times now, I don’t sense any judgment from Denis. The film is angry. It’s despairing and sorrowful. But Denis never takes on the role of judge, and certainly not from a fixed moral position.

LEARY: In theoretical discussions of ethics there is an important distinction to be made between virtue and morality or ethics. Morals require us to evaluate situations by specific codes or rational principles. These ethical codes pre-exist situations and can be argued and refined in academic ways. But virtue has more of a narrative component. Virtue is an attitude or disposition that compels us to navigate a situation in certain forms and over time develop our potential as decent human beings.

Your reference to curiosity and virtue in Rivette helpfully returns us to our initial question: What is Denis doing? Well, she is doing something virtuous. And her filmmaking is pedagogical in a sense, in that it’s training our eye to perceive people and the world in a certain way. I’ve been immersed in her films in preparation for these conversations we are having, and I find myself looking at the world in a different way. There’s a sense of hospitality present in her creative process, one bold enough to invite very scary and dangerous things into one’s perceptional home and subjective space. There’s almost a maternal aspect to her films, as she is willing to embrace these characters and situations for us and re-present them with the dignities of time, space, and composition.

3. Descas, Invitation, and Observance

LEARY: One of Denis’s guiding impulses as a director seems to be a pre-existing narrative or emotional familiarity with the performers she works with. She often talks about actors as if they have been invited into her craft or creative process. She’s even built her own little film history within film history by cycling the same actors through her cinema over time. We watch Grégoire Colin grow up in her films. Alex Descas is consistently present. There are several others we could mention.

HUGHES: Sure. Michel Subor, Isaach De Bankolé, Vincent Lindon, Alice Houri, Béatrice Dalle, Florence Loiret Caille. Yekaterina Golubeva’s few scenes in The Intruder are so indelible, but I’d forgotten until I revisited the film last week how lovely and heartbreaking she is in I Can’t Sleep. It’s become a little game for me each time I sit down with a new Denis film—that anticipation of spotting a familiar face, like an old friend. I have a real fondness for filmmakers who work with a core group of actors: Ozu, Linklater, Ford, Apitchatpong, Tsai.

LEARY: Denis arguably has a more diverse canon than a director like Ford, which makes her penchant for bringing this cast of characters together repeatedly especially intriguing. We spoke earlier of her as being interested in the configuration of people in a frame—their actual physical locations relative to each other. Seeing the same people under that same formal rubric, but in different genres or storylines is a benchmark of her cinema.

HUGHES: At the same time, even though they’re being dropped into new configurations, new genres, and new worlds, Denis certainly returns to certain actors for very particular reasons. Counting the short films, Alex Descas has worked with her nine or ten times now and in each case, even when he appears in only a single scene, he immediately occupies the moral center of the film. Did you notice he plays a doctor in three films (Nenette and Boni, Trouble Every Day, and Bastards)? And I’d totally forgotten about his brief appearance as a priest in The Intruder. I’m not sure if “moral” is the right word, but Denis seems to have a special confidence in, or admiration for, Descas.

LEARY: I like the idea that Descas is often posed as an impassioned observer. But you called him a “moral center” and then backtracked a bit from that.

HUGHES: I guess I never know what we’re describing exactly when we use the word “moral” in a context like this. The cliché of it muddies meaning. Maybe “stability” is better. In Bastards, for example, if there’s any hope, any respite from the nihilism, it’s that the doctor convinces the mother that she must watch that video at the end, to finally confront the horror with open eyes. Of course, if we were to treat Bastards as a work of strict realism, it would make no sense for a doctor to be involved with a former patient’s family in that way. But in the world Denis has constructed, Descas must be present at that moment. He’s like an embodiment of conscience.

LEARY: I think what most of us mean when we say “moral center” is that we notice a figure has a certain gravity. We are attempting to describe them as meaningful or stable. Alex Descas is almost like a reliable narrator for Denis in this respect. He is present with the viewer as an observer of Denis’s moral crises. In 35 Shots of Rum, Trouble Every Day, or even Bastards, he is the figure around which other people move. He is present in a way the other characters aren’t.

Denis has spoken of William Faulkner in her conversations about Bastards (which was influenced by his short novel Sanctuary), and she seems to have a penchant for Melville given the Billy Budd undertones of Beau Travail. Another way to think of Alex Descas’s characters in her films may be the reliable narrator characteristic of a certain brand of storytelling in American literature. By virtue of his stability and distance from the events in question, he becomes our point of access to the narrative complications of her cinema. I find it intriguing that without Descas’s character and perspective in Bastards, the subtext of the film would not have been made explicit. His performance embodies a critical or reflective movement in the film that would otherwise remain impossible for us as the viewer to enact.

HUGHES: No Fear, No Die might be the exception that proves the rule. There his character is driven insane by the inhumanity and chaos around him. We ended our conversation last time on similar grounds. I used the word “ethical”; you suggested that what Denis is doing is “virtuous.” Is this an example of what you mean?

LEARY: I think so. You had also deployed the word “wisdom,” which is an intriguing concept. Wisdom is the ability to comprehend something about our experience of the world that isn’t readily apparent. We have to be led to wisdom. We have to be wisely introduced to the differences between things that matter and things that don’t. The stability of Descas’s characters certainly embodies wisdom in this respect. I don’t think Denis’s films open themselves by analogy to theological, religious, or ethical vocabulary, but this persistent presence of Descas gets close.

Nietzschean Buffoons and Angels of Death

LEARY: So what about Grégoire Colin’s characters throughout the films? You’ve mentioned that he is often a point of comic relief.

HUGHES: I think so, yeah. Let’s face it, these aren’t especially funny films we’re talking about here! But when I think of the funny moments, they nearly all involve Colin. The way he hurls insults at Captain Brown in U.S. Go Home, the fantasy scenes in Nenette and Boni, the kitchen-sink seduction of his wife at the beginning of The Intruder. I think he’s hilarious in 35 Shots of Rum.

LEARY: My first thought when you pointed out he is often a comic relief is that he is some kind of Nietzschean buffoon. His moments of comedy intend to draw our attention to how imbalanced a situation is—or how often the act of taking ourselves seriously in a situation is really just the assumption of a godlike pose and control. And in comes the buffoon to maneuver a few pieces around to make a joke out of it and remind us that we are not in control of a situation or even our interpretation of it and we are subject to far greater powers and movements than we think.

HUGHES: I love that idea. Like the Holy Fool?

LEARY: Yes, that is a very close concept. Is he a Holy Fool?

HUGHES: I apologize for coming back again and again to 35 Shots of Rum, but between the two scenes we discussed in our first conversation—the dance at the restaurant and Lionel’s return home the next morning—there’s a short scene in which Noé (Colin), Josephine (Diop), and Gabrielle (Nicole Dogué) sit around a small table in Noé’s cramped kitchen. They all look exhausted, a bit hungover. They’re drinking coffee. Diop and Dogué do little in the scene other than react to Colin, who wanders around manically before noticing that his cat has died. Noé picks up the cat by the scruff of its neck, eulogizes it briefly, carries it through the kitchen, and then tosses it into a garbage bag. The comedy is all in Colin’s gestures—his straight face and the way he holds the cat at arm’s length—combined with Diop’s response. Colin squeaks the cat toy; Diop raises her hand to her face in horror. This is maybe the only scene in a Denis film where I can imagine there being a dozen takes that were ruined by actors laughing. Diop and Dogué are hiding their faces behind their hands through most of it.

LEARY: Colin is so dispassionate about disposing of the cat. I’ve always wondered if this really was a part of the script.

HUGHES: There’s an insert shot of the cat in the bag, so it was definitely scripted. Is Colin dispassionate, or is he deadpan? He has a bit of Buster Keaton in him, I think. Think of the scene where Boni and the boulanger (Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi) have a cup of coffee, and he sits there totally silent and straightfaced.

LEARY: Deadpan is a good word here. So why does the cat have to die?

HUGHES: After disposing of the cat Noé announces he will sell his flat and take a well-paying job in Gabon. The cat was his last remaining obligation to this little community. Of course, he’s also forcing the issue with Josephine, giving her an ultimatum of sorts. “You’ll ditch us and go away?” she asks. I suspect that one reason I love 35 Shots of Rum so much is because my wife and I often communicate via passive-aggression, so the spoken and unspoken dialogue in this film is right on my wavelength!

Again, I’m always reluctant to spend much time interpreting symbols in art as complex as Denis’s, but if you’re searching for a domestic memento mori, a dead cat in the kitchen is a pretty good one. Death is ever-present in this film. Josephine’s mother is gone, Noé’s parents are gone, René (Julieth Mars Toussaint) retires and then commits suicide, and there’s the growing and shared realization that this makeshift family is coming to an end. Like all of us, though, they’re reluctant to acknowledge it. What did you call it earlier? A “godlike pose”? Colin’s performance punctures that façade.

LEARY: So to speak again of the Nietzschean buffoon, it’s not that God is dead but the Cat is dead!

Even in Beau Travail, the affinity the other Legionnaires feel for Colin’s character derives from his humor. He is a capable soldier but he is also winsome and engaging, which is the essence of his subtle mutiny.

HUGHES: This is a throwaway comment, but one thing that struck me during this latest viewing of Nenette and Boni is that Boni’s fantasies—his sexual fantasies—become increasingly domestic. The “God Only Knows” scene is him imagining a husband and wife just being together. Not having sex. Just flirting and enjoying each other’s company. I found it really touching because domestic life is completely alien to this kid. His mother is dead and he’s alienated from his father. So which is his deeper desire? To fuck the boulanger or to be part of a family? Colin, more than anyone else in Denis’s stable of actors, walks that line between comedy and pathos.

I mentioned Yekaterina Golubeva earlier. I think she occupies an interesting place in Denis’s cinema. Aside from Bruni-Tedeschi in Nenette and Boni, she’s really the only blonde that Denis has worked with, and in a cinema filled with outsiders and preoccupied by border crossings and migrations, she’s the only Eastern European. In I Can’t Sleep, she’s our introduction to this community, but she never becomes fully enmeshed in it. She enters alone, leaves alone. She functions in a similar way in The Intruder. Again she’s an outsider and is almost like an angel of death, appearing from time to time to haunt Trebor (Subor) like a specter.

LEARY: She’s certainly an angel of death in The Intruder, but she also seems to embody a sense of justice. If I read the narrative correctly, she is physically responsible for whatever grisly act led to the image of the disembodied heart on the snow. However, in I Can’t Sleep she is more of an observer. She is puzzling out the mystery of these two guys in her hotel in a Hitchcockian way. She only steps out of her observer role when she makes off with their loot at the end.

HUGHES: It’s interesting that you called her an observer. We’ve spent a lot of time talking about how Denis looks at the world, but it’s worth noting that Denis also populates her films with anonymous witnesses. I’m always fascinated by the Africans who sit on the periphery in Beau Travail, or the crowds who watch Camille’s (Richard Courcet) lip-synch performance in I Can’t Sleep. I’m sure we could trace this line of observers through all of her films. One of my favorite instances is after René’s retirement party in 35 Shots of Rum, when he and Lionel are talking on the train. René is in despair as he acknowledges the pain of having to surrender to his situation, to his age, to his loneliness. “I’d like to have died young,” he tells Lionel, “But I’m at the age I’m at.” It’s a quiet, intimate moment between the two men, but Denis punctuates the scene with a cut to a white Frenchwoman who is sitting a few seats away. It’s a small but essential move because it situates this everyday tragedy in a social space. It’s another moment that gives me a sharp pang of embarrassment. Like that anonymous woman, I’ve witnessed something private.

Hidden Economies

HUGHES: Have you seen Richard Linklater’s first film, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow By Reading Books? Most of it takes place on a train, and I’ve heard Linklater say that when you ride a train in America you see the backs of cities. The railroads are 19th-century infrastructure, and as our cities have evolved, everyone who can afford to has moved far away from the tracks to escape the noise. I think that’s a fascinating and useful concept—seeing the backs of cities, exposing the parts of our world that are seldom seen. It’s loaded with economic and racial freight (pun intended), and it’s a persistent concern of many of my favorite artists, including Denis.

On page after page of my notes, as I rewatched her films, I scribbled the words, “alternate economy.” I Can’t Sleep is about a small group of people who live in the same hotel, but it’s also about an international phonecard scam. Nenette and Boni is about young siblings trying to survive, but it’s also about the black market in Marseilles and the life of a pizza-truck worker.Trouble Every Day is partly about a hotel maid, 35 Shots of Rum is about train workers, White Material is about the hands-in-the-dirt work of growing coffee, and Bastards opens the doors to human transactions of the vilest kind. This aspect of Denis’s work is too seldom commented on, I think: she has a deep and abiding concern with money. In I Can’t Sleep, Descas’s character is a carpenter who argues with a white woman who tries to cheat him out of a few dollars. Later we see Camille pay the person who made his costume. And, of course, the film ends with Daiga (Golubeva) taking the killers’ money and driving off alone. I Can’t Sleep is Denis’s L’Argent—or one of her many L’Argents. Who but Claire Denis would film that scene in Bastards when Marco (Lindon) talks to his insurance agent about accepting the early withdrawal penalty? This is not the kind of thing we’re supposed to see in movies.

No Fear, No Die is the best example of what I’m getting at. Cockfighting epitomizes these alternate economies but it also gives Denis an opportunity to work through post-colonial concerns. In fact, the classroom discussion of Fanon in 35 Shots of Rum feels almost like an eighteen-year callback to her depiction of the relationship between the two cockfighters and their white boss. What most interests me about No Fear, No Die, though, is the long sequence near the beginning of the film when Denis leads us step-by-step through the massive, labyrinthine complex where the fights take place. I can’t imagine what this facility is in real life, but Denis seems fascinated by it too. There’s a long scene where the boss shows off his disco, and Denis just waits there with them as the lights spin and whir. That film and Nenette and Boni both show us the back of Marseilles. I mean, Denis forces us to really look. It reminds me almost of what Pedro Costa has done in his Fontainhas films.

LEARY: If I am hearing you correctly, there is a Dardennes-like element to this social exposure in her film. Yet curiously she does not have an overt ethical conscience—she doesn’t use these subterranean economies to make some kind of point about society and its imbalances. She’s simply present for them.

HUGHES: Exactly. I’d love for this conversation to spark a wave of Denis criticism that approaches her work in the same terms that we all use to describe the Dardennes. The trick, as you mentioned earlier, is that she resists the readymade language of transcendent morality. She is . . . I have this image in my mind of a flat-head screwdriver being hammered into wood, chipping away, revealing what’s underneath.

LEARY: The realist appeal of her films is the way we, along with characters like Descas’, are observing these transactions and the configurations of people that occur as a result. And there is a paradox built into these social economies. As we see in No Fear, No Die the cockfighting business is really alienating. It requires an African and/or West Indian, who by simple provenance knows cockfighting better than anyone else in the world. These specialists speak a different language than those that populate the Parisian underworld. They live with the birds. Their structural experience of the city is fairly limited to this vocation.

However, all the guys making money off of the cockfighting business are from much different cultural and social backgrounds. This is a point of simple sociology: the people on either side of the cockfighting business are much different from each other, yet they need each other. Both parties must be present to make the economy of cockfighting work. Similarly, in I Can’t Sleep, Daiga has figured out who these two flashy guys are and then makes off with their cash. She understands the reprehensibility of what they have done as thieves and murderers, but now she is bound to them by taking their money.

We could say something similar of Chocolat. Protée (De Bankolé) is desired by the white woman. But despite rejecting her advances, he remains a servant of the family. Financially he is bound to her even though he is alluringly distinct or alien to her. Or Mona (Dalle) and Théo (Descas) in I Can’t Sleep. He wants to leave Paris and return to Martinique, but they are bound together sexually and romantically and they have a child together. Mona can’t understand how this desire could outweigh their relationship, but it does.

This concept of people alternately repelling and embracing each other has a very dancerly feel to it. The way you have described this as “transaction” and “economy” makes sense of that very formalized sense of movement in her work.

The Seat of Emotion

HUGHES: Marco and Raphaëlle (Chaira Matroianni) in Bastards fit that description as well, which reminds me of a question I wanted to ask you. The last time I watched Bastards I was struck by how beautiful it is. Denis’s films are often beautiful, but I guess I was surprised both because it’s her first narrative feature shot digitally and because the content of the film is so ugly. But those shots of Mastroianni on the stairs with Lindon’s hands on her neck—they’re sublime. And so this generic question: what function does beauty play in that film or in Denis’s films in general? As I am judging the worth of a film, beauty isn’t necessarily a criterion. But when a film is so beautiful, that beauty has a textual function, it manipulates us, it changes our relationship to the characters we are meeting in this world.

LEARY: In talking about Denis as a beautiful filmmaker, my instinct is to return to our earlier conversation about the way Denis sees things. Her mise en scene is distinct enough that it’s hard to start listing comparisons. Petzold comes to mind as someone who thinks of objects and spaces in a similar way. I think it would be interesting to talk about both Petzold and Denis as doing the work of European historians in the mode of cinema.

In this most recent pass through her films I’ve also thought of Wes Anderson. He is often slated as a great formalist or mannerist, and obviously his sets are very ornate. His wall treatments, the furniture and clothing are full of color and life. But Denis has many of these same qualities without even trying. In her Parisian films, she captures the domestic routines of Eastern European or African or West Indies immigrants. The edges of her frames become organically populated with their vibrant material cultures.

In I Can’t Sleep, for example, many of the flats are coated in loud wallpaper and textile. We have these ethnographically appealing scenes of immigrant communities dancing with each other in 35 Shots of Rum and I Can’t Sleep. If you knew nothing of immigrant culture in Paris, a survey of Denis’s films would at the very least introduce you to the way people choose to decorate their living spaces. This beauty in her films simply emerges from her actual locations. Who knew that a rice cooker could be something just worth looking at for a little bit?

This attention to detail extends to the role different objects play in her films as well. In Chocolat, we have the ants smeared on a buttered slice of bread. A baby moving in utero and a finger in the frosting of a bake good in Nenette and Boni. A Yankees cap at the beginning of Beau Travail. In L’Intrus, the disembodied heart or the mattress they lug across the bay to the island. The “white material” of White Material. She populates her films so effortlessly with the raw material effluvia of stories. To me, that is beautiful. Denis is not an eloquent filmmaker in that she simply wants to arrange people and objects in an articulate way. Rather, she is a very cosmopolitan filmmaker. She has a vision of the world in which people express themselves with great physical, emotional, and domestic differences—yet they are smushed together in urban landscapes such as Paris. For Denis that’s a beautiful thing. She doesn’t always have to talk to us through set design because the city already exists. Why not just film that?

HUGHES: I think it’s interesting that in our first conversation, when we were discussing subjectivity in Denis’s films, we eventually circled around to conclude that yes it is about subjectivity but it’s also about something else. There is always something else. I agree with everything you just said and am fascinated by it in the same ways, but there’s another aspect of this. I rambled earlier about how Denis shows us the back of Marseille in Nenette and Boni. However, she doesn’t just drop us into this decaying flat where Boni and his friends live, as if a documentary crew has arrived unannounced. Instead, she dresses one wall of his room with a deep blue tapestry just so she can film Grégoire Colin in a pink pullover standing in front of it. The mise en scene in that film is straight out of Jacques Demy! Critics often note that Denis’s best films have been made in collaboration with Jean-Pol Fargeau (screenwriter), Agnès Godard (cinematographer), and Nelly Quettier (editor), but her production designer, Arnaud de Moleron, deserves a lot of credit too.

Moleron didn’t work on Bastards, but my favorite example of Denis and Godard’s color fetish is the scene where Marco shows up late at night at the hospital to visit Justine (Lola Créton). He’s just discovered the sex den (I have no idea what else to call that place) and spotted the corn cobs on the floor. Denis cuts to the hospital, where Marco is talking to a nurse and they’re both completely bathed in rose-colored light. The hospital is pink, in a film noir. It’s pure expressionism.

LEARY: Speaking of expressionism, Vers Mathilde directly addresses the question of beauty in her cinema—or of an aesthetic for her cinema. Whatever is happening in Vers Mathilde gets a bit obtuse, but the theoretical lines of direction are clear. For Denis, cinema starts when a body begins moving through a particular space. Cinema can be beautiful because bodies move in certain ways; they attract and repel each other in certain ways.

HUGHES: The ribcage is “the seat of emotion,” Mathilde Monnier tells Denis. There’s a scene in Vers Mathilde where a male dancer is experimenting with a movement. He’s spinning and landing hard on one foot. Even to my untrained eye the gesture is inert. Then Monnier interrupts to ask, “Where could it take you apart from a circle?” He stops, thinks, resets, edits his movement, and suddenly the gesture comes to life. I don’t want to push this too far, but that is how I imagine Denis with an actor—giving them freedom to be themselves, to work intuitively, but then she is constantly looking, observing, judging, making small tweaks to that body, to that movement.

LEARY: That is where the cinema thought begins. It doesn’t begin with a scene or a concept. When I hear her talk about method, she defaults to describing someone moving expressively through space and what that space is and how this body will eventually connect to others. Watching her cinema through the lens of Vers Mathilde makes me rethink why I find other films pretty or beautiful. She has set a bar for me through the sheer humanity of her method.

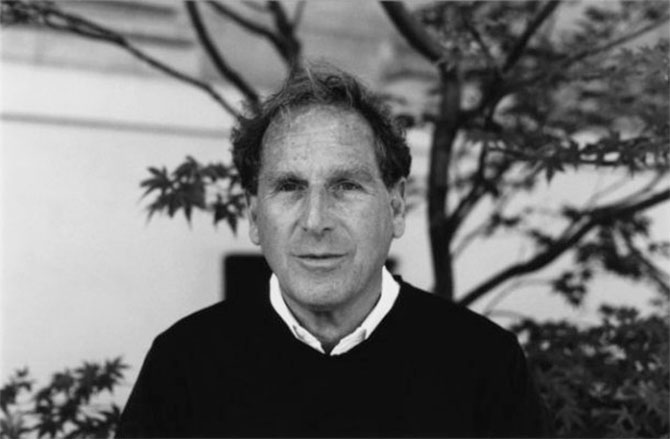

4. Interview

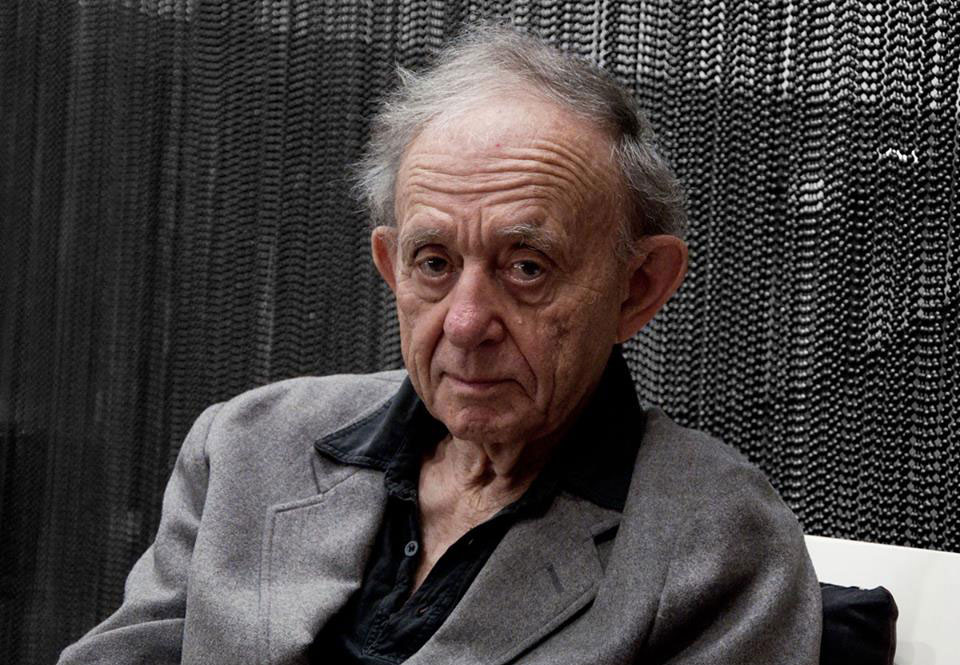

Claire Denis’s short film, Voilà l’enchaînement, debuted in September 2014 at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it played in the inaugural Short Cuts International program. The film is a series of monologues and conversations performed by Norah Krief and Alex Descas, who portray a mixed-race couple whose relationship begins, welcomes children, and disintegrates violently, all within the span of thirty minutes. Formally, it’s unlike anything Denis has done before. The closest precedent is perhaps Vers Nancy (2002), a short film in which philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy and a young woman debate “foreignness” as a concept while Descas, a dark-skinned embodiment of their signifying language, wanders just outside their view. Composed entirely of tight master shots and staged in an unadorned room, Voilà l’enchaînement is a bitter and pensive exploration of commonplace racism.

In addition to debuting her film, Denis was in Toronto to serve as a Governor in TIFF’s Talent Lab, a comprehensive four-day program in which she, Jim Stark, Sandra Oh, and Ramin Bahrani mentored twenty young filmmakers. I spoke with her about her long relationship with TIFF and about the role of activities like the Talent Lab in her career as a filmmaker. She also generously agreed to discuss several of the topics that came up in my and Michael’s conversations.

“It’s Still a Mustang”

DARREN HUGHES: I’ve spoken with you one other time and have seen you give several Q&As, and in each case you’ve been uncommonly engaged with the audience. Discussing your work seems to be an important part of the job to you. For example, you’re here this week with the Talent Lab and have a very busy schedule. It would have been easy for you to say no to my request.

CLAIRE DENIS: It’s not easy to say no to certain propositions because it’s a way to . . . I don’t have an appointment every day with my work. It never happened. I must say even that I have a fear of overlooking my work. I prefer to dig, to dig, to dig blindly, you know?

HUGHES: A fear of overlooking your work?

DENIS: It’s not pretentious what I want to say. I never could organize myself as a professional with a career. One film was finished and there was this sometimes painful feeling [afterwards], so the source of the next one was in this pain. There is a hope always of doing a better film, for sure, even the hope of being acclaimed as the best director in the whole world, but this hope is not as strong as it should be. Need is there, and need is driving me.

At the Talent Lab, I told everyone that I feel like them, like a young filmmaker. My experience is not the experience of someone who has tamed filmmaking. No. Not at all. For me, it’s still a mustang or a wild horse. It’s true. Each time, I try. That’s all I can say.

HUGHES: How does an experience like the Talent Lab function in your day-to-day life as a filmmaker?

DENIS: Those young filmmakers think I am a very emotional person and they think that I’m being humble or whatever. I do not like to speak about myself as a professional filmmaker, but it’s not humility. I’ve always felt, since the very beginning, there was this small line between amateur and professional and that maybe I like to be on the border. Well, I don’t know if I like it, but somehow I was on the border.

HUGHES: Has that position allowed you to make the films you’ve wanted to make?

DENIS: Yes, but it’s not a freedom, because I feel constantly guilty for not being more like a professional. I mean, I stick to the budget, I know what the budget is, I like to make small-budget films, so I feel free. I know all the things I should know. I know when the script is not going well, when something is wrong with the script. On the set also I feel when something is coming to life after three or four days, and I know that if I don’t feel that I will be in big trouble. It’s a process: do everything for the film, scriptwriting, the thinking before, work on the music, work on the color with my DP, and of course work with the actors, but that preparation is not to settle stuff. It’s to be sure we are all going to take the same track. And then, after a week, I get an answer. After three, four days, I realize, yeah, it might work.

HUGHES: When I interviewed you about 35 Shots of Rum, I asked about White Material, which was then in post-production, and you said that 35 Shots of Rum was an easy film and that White Material still needed more work. Is that what you mean?

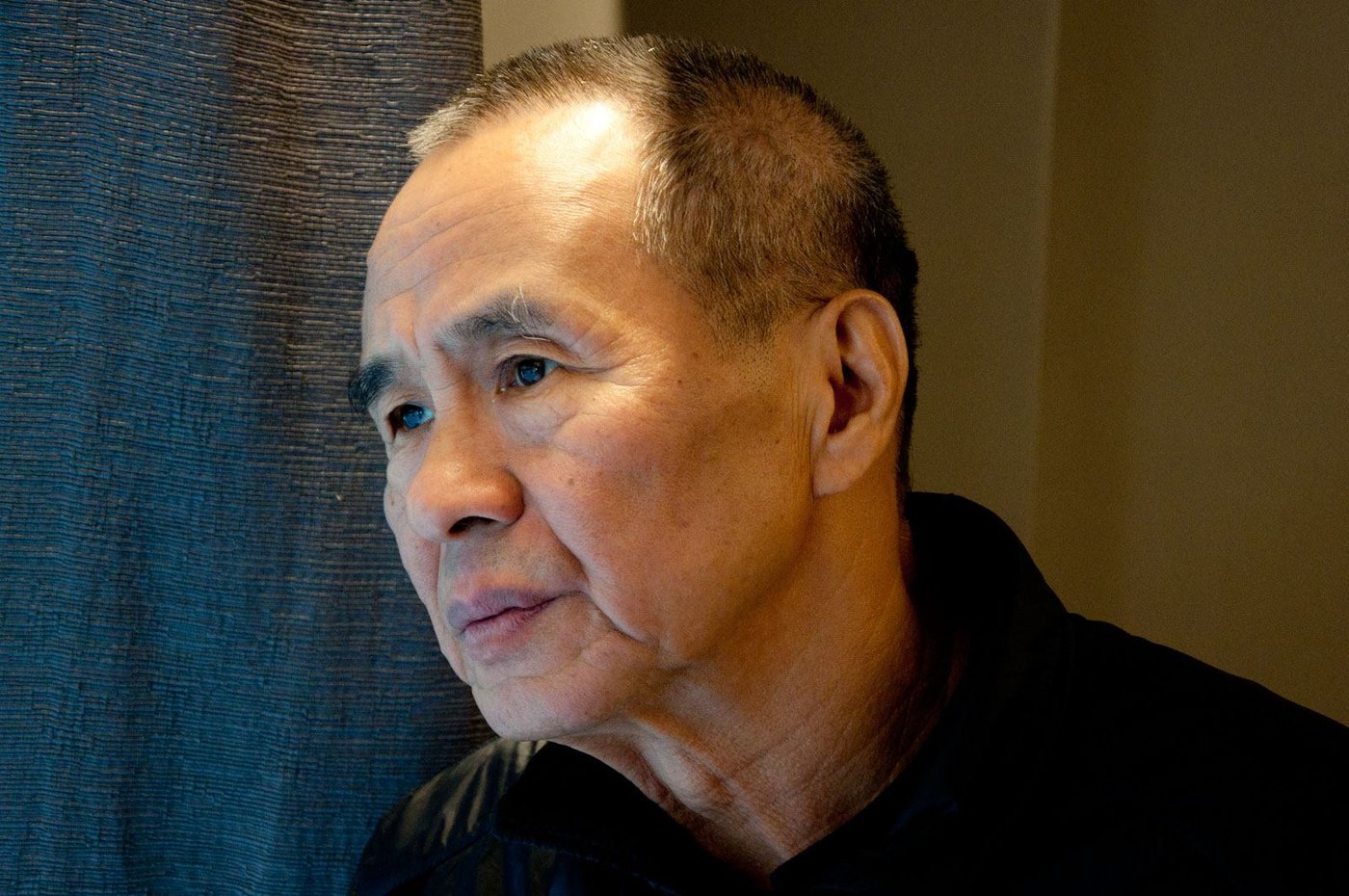

DENIS: 35 Shots of Rum was in me because it was an homage to my grandfather and my mother. It was their story in a way, transposed into another world and today. And I’ve known Alex Descas so well for so long, so I knew that I could hand him my grandfather {laughs}. When I met my grandfather he was older. I never knew him well. But through my mother’s memories I thought, “Alex, this is for you.”

I knew every day I was walking along with them. Maybe also the Ozu movie [Late Spring (1949) was a direct source of inspiration] was there with me and all of the tears I’ve shed while watching it. It’s not sad, the Ozu film, but it says, “This time is finished. This relationship won’t be the same again ever.” For me it’s heartbreaking. It was easy for me because I was going every day on the set, and I knew [Descas and Mati Diop] were both holding the character in them. I was there to put the camera where I should.

HUGHES: You make it sound so easy.

DENIS: No, it’s true. It is true. It is true. It’s not “aha!” It was the only time I felt I was in sync completely with myself, with the film, with the light, with the location. There were no obstacles for me. I don’t mean that the film is perfect, you know, but I mean there was something fluid in me, like tears.

HUGHES: Last week was the first time I’d revisited 35 Shots of Rum since I became the father of two daughters, and I can tell you that I now feel about that film the way you just described Late Spring. Basically, from the moment Mati Diop turns on the Harry Belafonte song, I was a wreck.

DENIS: {smiles} I will never be the father of two daughters, but my mother, she’s an old lady now, she can openly tell her children that the man of her life was her father not our father.

“Let’s Go Piece by Piece”

DENIS: But, you know, White Material was easy also. My collaboration with Isabelle was working like two ballet dancers. Everything I wanted, she guessed, she knew. She knew I grew up in Africa and that this was the type of woman I would have met. After a while I realized she was slightly imitating me. But strangely, not in a very open manner, and maybe she was not even aware of it. And so we kept that secret. She was my warrior.

What was difficult is that I thought I was going to shoot in another country, not in Cameroon, because I wanted to shoot in a country where I knew no one. I didn’t want to be the woman who did Chocolat, blah, blah, blah. Between the time I made Chocolat and White Material, a lot of things had changed in Francophone Africa. I originally wanted to portray Ivory Coast—the way all of the French coffee and cacao growers had to go away with the French army—and I hoped to shoot in Ghana, which is like Switzerland and everything is peaceful and rich. But they don’t grow coffee anymore in Ghana because it doesn’t bring in enough money. So I had to go back to Cameroon. I knew every place. It was so emotional going back to Cameroon, and that was hard.

You know, the army had only one helicopter and we waited for it for weeks. The producer would call me from France and say, “But Claire, I don’t understand. Those guys are your friends. Can you tell me why we haven’t gotten our helicopter?” {laughs} And I’d say, “Well, there’s only one helicopter for this country, and I asked to use it for free, for the cost of the gas.” It’s not so easy. If you’re willing to pay a lot, you go to the petroleum companies and you can have ten helicopters. We didn’t have that type of budget. We had to deal with a comradely relationship and trust.

HUGHES: I hope this isn’t an indelicate question, but how does financing shape your scenarios? For example, I’m thinking of that sequence in The Intruder that takes place in South Korea, and in 35 Shots of Rum, Lionel and Josephine make a quick trip to Germany. Were those scenes written to meet financial agreements?

DENIS: No, no, no. When I was writing The Intruder, I was obsessed with Jean-Luc Nancy’s book about his heart transplant, obviously, and I thought, there are two halves in the heart and maybe it was like going from the northern hemisphere to the southern hemisphere. Immediately, I was thinking about Robert Louis Stephenson when he was sick. A lot of men of the 19th and early-20th century had the feeling that, for a man, the South Pacific islands are paradise, and it’s not true. So I decided that there should be a place where he’d wake up with the new heart and, because I’d been many times to South Korea and China, I knew about the massage that the blind woman could do. They really feel everything in your body, and I thought, maybe instead of filming a surgical room, it would be better to have this blind woman feeling the scar.

I spent three months in the South Pacific, traveling on the boat, writing the script, because I knew nothing there. And suddenly, when I was there, I felt a terrible melancholy and sadness. Those islands are beautiful, and somehow you feel . . . {exhales deeply} . . . you feel blue. You feel doomed somehow. So many people told me that after he made Tabu (1931), Murnau came back to the United States different, moody.

The financing was very little to start with. A fantastic producer, who is dead now, managed it so that we shot piece by piece. Jura in Switzerland was a place I knew very well—even the house I knew, the lake, everything—because someone in my family used to live there. Andre Bazin said, “Let’s go piece by piece,” and that’s what we do. One day I said, “We have to go back to Jura because there is snow.” So we went with a small crew.

Everything I shot in Pusan was x-ray’d at customs when we went back to France. All of the stock was ruined. Nothing was left. It was gray. It was burned. The airport told us that that day there had been an alarm and they had doubled the power of the rays, so it was erased. I called some friends in South Korea—a film director and the director of the Pusan Film Festival—and I told them, “Everything I’m sure was great, but it’s no more.” And they managed to find film stock for me. The hotel gave me a room. The company who was building the boat also owned Korean Air. So I was able to redo it.

HUGHES: And all of that was possible because of the relationships you’ve built over the years?

DENIS: But I didn’t know I had that kind of relationship with Pusan! How could I imagine those South Korean people who laugh at you because you’re not drunk enough, or whatever, would do this? {laughs} South Korea is a land of filmmaking. They have something. The whole crew was cinema students. Cinema is important in South Korea, and not in the sense of only making money. It’s an artistic form that is well respected.

“I Never Thought That I Was Filming Bodies”

HUGHES: In our conversations, Michael and I found ourselves talking quite a lot about Alex Descas, who appears in so many of your films. His performance in Voilà l’enchaînement typifies, I think, a few tendencies in your work.

DENIS: In this case, it was completely accidental. Alex and Norah were asked to make a lecture at a theater festival last summer, and there was a carte blanche to a French writer, Christine Angot, whose last novel was about a couple who are . . . more than separating . . . almostdestroying themselves, and about the consequences for the children. A huge book. The father is a Caribbean black man in the book, and the mother is a French white woman. Christine was attacked by the real mother—because it’s almost a real story—who recognized herself, and she lost the trial and had to pay a lot of money. So she decided to make a small lecture from dialogues from the book.

I was not aware of that, just that she cast Alex and Norah. She called me and said, “I’d love to have you come to Avignon to listen to this lecture.” I came, and when it was finished we went to dinner and I said, “Wow. If I could, I would film it immediately.” Because the way they respond to each other . . . it’s funny but it’s dramatic, yet it says a lot about what is racism and what is not racism. It’s sometimes hidden even through a love affair and making children.

At that time I was working in an art school in the north of France. The school always asks the people who go there—like Pedro Costa or Bruno Dumont—if they agree, to do whatever they want, with nothing but the equipment of that school and, of course, no real budget. So I immediately said, “I know what I’m going to do.” On a black wall in their little studio with nothing. It was so different from what I normally do. I thought I was filming words, filming words of people who try to be a couple but something is wrong right from the beginning.

HUGHES: You’ve worked often with a small group of actors, of course, but it wasn’t until I rewatched all of the films together that I noticed how you often use specific people for specific functions. For example, Alex is often a stabilizing presence in the films. He’s like the moral center of your universe.

DENIS: Yeah, yeah.

HUGHES: So this is something you’re conscious of?

DENIS: For me, Isaach [De Bankolé] was also in my first film the stable center, the moral center. And he was the stable center again in my second film, where Alex was more fragile, which was a reflection of their real relationship. Alex was having a bad time in his life, and in their real friendship in life he could lean on Isaach. I knew that.

Alex is such a good father with his own children, so I felt that he would, even in dire straits, do the right thing, he would never lose his mind or his balance. For his children he would be always, for me, perfect, the most reliable person, and it affected me to see that because I knew his children as babies.

HUGHES: Near the end of No Fear, No Die, both Alex and Isaach have passionate, emotional outbursts, which is actually quite rare in your films. Your characters are typically quiet and self-contained. I mention it because it’s interesting how the character and tone of their voices change when they speak loudly. Isaach’s becomes nasally almost, like he’s speaking from the very back of his throat. Critics often talk about how you film bodies, but I wonder also how an actor’s voice affects your directorial decisions.

DENIS: This is a mystery to me, I have to say, because I never thought that I was filming bodies. {laughs} I’m filming characters, you know? And I always think, if I am not, like in No Fear, No Die, walking with them, if it’s a static shot, then I must have space to see the movement. I don’t see why I do more bodies than other directors.

HUGHES: There are definitely recurring shots. You’ve certainly filmed more shoulder blades than any other director I can think of.

DENIS: In Bastards, it was almost a caricature of a woman looking at a man. Certainly, Vincent [Lindon] also when he was in Friday Night naked, I was amazed by his shoulder. Nakedness I’m not interested in but the body is always very emotional. It shows something. An actor can think about his part, an actress can think about her part, but suddenly the body will give them a reason. The way they walk. They don’t control everything, and they adapt to the film in a way. Also, they have to adapt to the location.

HUGHES: My favorite moment in Vers Mathilde is when a male dancer is repeating a movement over and over again, and Mathilde steps in and makes a small suggestion—something like, “What would happen if you didn’t move in a circle each time?” He adjusts his movements and the gesture suddenly comes to life. It gives me chills. I like the scene also because it shows the level of trust between Mathilde and the dancers. She gives them freedom to experiment but she’s also a critic and editor. Is that similar to the job of a film director?

DENIS: I think so. When I work with Mathilde, she’s like my sister. We both must be aware when a movement is becoming a trap for the actor or the actress. When an actor thinks that maybe he should stand up like that, or make a violent movement to open up a window, it’s easier to say something about the movement than to make a psychological interpretation of the movement, which might make the actor or actress think he or she has misunderstood the character. Instead, by telling that person to maybe try without slamming the door and entering slowly into the room, this little suggestion is not a judgment on the way of acting. If you said, “no, no, no,” it’s terrible on the [working atmosphere of the] set. But by just saying, “Let’s try not slamming the door, walk slowly,” it gives sort of a peaceful moment for the actor to experience something else. And it will affect, I’m sure, his understanding of the moment without me telling him, “no, no.” This I cannot stand, because it’s as if I was not trusting the way an actor or an actress translates the character.

I remember when I was filming Isabelle Huppert, driving the tractor or riding on the motorbike, suddenly she was walking completely differently. She was not like she is in France.

HUGHES: That’s my favorite thing about White Material—getting to watch Huppert climb on a truck and dig in the dirt.

DENIS: She was immediately at home. It’s a part of Cameroon where they grow coffee, and she was almost part of the thing. She knew it, and she enjoyed that too. I didn’t need to tell her, “Touch the hair of your son and notice that it has been cut.” No, no, she’s on the tractor and, of course, she understood.

“It’s a Way of Living”

HUGHES: I’m fascinated by the massive complex of buildings where the cockfights are held in No Fear, No Die.

DENIS: It’s a food market.

HUGHES: Really? You spend five or ten minutes early in the film just leading Alex and Isaach’s characters—and the audience—through the maze of hallways. There’s a long scene where we watch disco lights spinning.

DENIS: There is everything in this food market. Hotels, a disco, a restaurant. It’s a world.

HUGHES: That’s exactly what I was hoping to get at. Richard Linklater’s first feature, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books (1988), takes place mostly on a train, and I remember hearing him say somewhere that he likes trains because when you ride them you see the backs of cities. Your films often do that too.

DENIS: You know, I have to say that I like Boyhood very much. I shed a tear! Patricia Arquette is probably my favorite actress in a long time. She’s someone I want to touch, like Isabelle Huppert. Isabelle, I want to touch her, I want her to be mine. Patricia Arquette is much more solid than me, but I think also she’s touchable. She’s what I like in an actor, that you want to hold them.

HUGHES: I’ve heard you say something similar before, that you feel almost possessive of your actors.

DENIS: Yes, but it’s not in the sense of jealousy or whatever. But I like to touch them. I remember Grégoire Colin, this young actor in Nenette and Boni and U.S. Go Home, when I met him he was fifteen and how he’s in his 30s. He’s a father, and when his baby daughter was born he came to me in the editing room and he said, “Hello, Grandma!” {laughs} And I understood because he was my boy! He told me he was going to have a child and suddenly I was like a mother: “You’re not too young?!”

HUGHES: That’s wonderful! I don’t want to lose this other line of thought, though, this idea of seeing the backs of cities. In my conversations with Michael I called it your interest in “alternative economies.” It’s not just the cockfighters in No Fear, No Die. I Can’t Sleep is about a small community of characters, two of whom happen to be serial killers, but it’s also about a phone card scam. Nenette and Boni is about a few days in the life of a brother and sister, but it’s also about the black market.

DENIS: Well, the black market in Marseilles is ridiculous.

HUGHES: But I’m wondering about how these other concerns find their way into so many of your scripts? Does it come out of your collaboration with Jean-Pol Fargeau?

DENIS: With No Fear, No Die, I got money from German TV for my script, and I was supposed to shoot in, at that time, West Berlin, in the compound of the French army, where there were French restaurants. I thought these two guys, they knew cockfighting. There are many places where clandestine cockfighting exists. We were in preproduction in Berlin and the wall fell. So I changed the script with Jean-Pol because suddenly the black market was everywhere, even an old grandmother from Poland would come selling cookies. But then I thought, “No, this is not fair.” And then, also, the subsidies in Berlin went down because they had too much to deal with. I knew the food market, and I thought, “The food market is a world in itself, like West Berlin.” So we transferred the story, and I told the producer, “If you trust me, I need only a week to change the script, the location I know, and I will shoot in five weeks so we don’t lose money.” It was a great experience.