Dir. by Pedro Costa

Pedro Costa’s second feature, Casa de Lava, opens with a barrage of arresting juxtapositions. The first few minutes pass in complete silence as we watch the simple white-on-black credits, followed by a montage of volcanoes. It’s found footage, I assume — all grainy and pulsing, like scenes from a seventh grade science documentary — but Costa’s syncopated cutting turns it strange and abstract. Music enters at the two-minute mark, and it’s likewise complex and counter-rhythmic. Paul Hindemith’s viola sonata serves double duty here. Its atonal bursts of dissonance disturb the beauty of the nature sequence, but it also alludes to High Modernism and acknowledges the “outsider” perspective of the filmmaker. This film about Cape Verde, the former Portuguese colony off the west coast of Senegal, is the work of a Portuguese director and a European economy, and it would certainly find its largest audiences among First World festival-goers and cineastes.

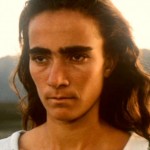

The sonata continues, but Costa next cuts together a montage of miniature portraits. He frames the women of Cape Verde in close-up, shooting their hands, the backs of their heads, and, most often, their expressionless faces. The women share several particular traits: thick eyebrows, pronounced cheekbones, freckles, and whisps of hair on their upper lips. They have centuries of colonialism, slave trade, and miscegenation written into their DNA. As for why Costa shoots only women: in the closing seconds of the sonata’s fourth movement, Costa cuts to what we eventually learn is a construction site in Lisbon, where several Cape Verdean men are working. It’s really a remarkable feat of filmmaking. In less than three-and-a-half minutes Costa has established the central conflict of the film — that is, the perilous relationship between colonizer and colonized and the complex history (economic, political, cultural, and familial) they continue to share — and he’s also implicated himself and the audience in that history.

The feat is even more impressive given the mixed quality of Costa’s first film, O Sangue, which, while stunning to look at, doesn’t quite work aesthetically or even at a basic narrative level. It’s a very personal film — the first of Costa’s many attempts to rescue on celluloid the family he was denied, personally, as a child — but like many first films its admirable ambitions are hampered by inexperience and by a too-obvious debt to his influences. (O Sangue is the only Costa feature I’ve seen only once, so I’ll leave it at that.) By contrast, Casa de Lava is much more assured and coherent. Costa claims to have begun the project out of anger with Portugal’s turn to the right amidst the formation of the European Union, which precipitated a dramatic restructuring of the nation’s economy, including the privitization of television. The few sources of funding in Portugal’s small film economy dried up. “I was so disgusted that I told Paolo [Branco, his producer] that if he’d give me some money I’d go to Africa and make something there.” (See Mark Peranson’s “Pedro Costa: An Introduction” in Cinema Scope 27 for the rest of the interview. It’s well worth tracking down.)

Costa’s own description of Casa de Lava reads like a ghost story:

In the beginning there is noise, desperation and abuse. Mariana wants to get out of hell. She reaches out her hand to a half dead man, Leao. It’s only natural, Mariana is full of life and thinks that maybe the two of them can escape from hell together.

On the way, she believes that she is bringing the dead man to the world of the living. Seven days and nights later, she realises she was wrong. She brought a living man among the dead.

Like a mash-up of Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie and Claire Denis’s Chocolat, Casa de Lava concerns a young woman, Mariana (Ines de Medeiros), whose exotic notions about the Other are tested and refuted by first-hand experience. The hell she wishes to escape is the mundane, lonely existence of her daily life as a nurse in a Lisbon hospital. Costa connects Mariana with her supposed savior, Leao (Chocolat‘s Isaach de Bankole), early in the film, when, after being injured at the construction site, he is brought to her in a coma. It’s another fascinating and unusually efficient sequence of images. We first see Leao at the site, staring without expression into the distance; then the film cuts to another worker, who is bringing news of Leao’s fall to the foreman. (Or, I assume he’s speaking to the foreman. Costa rarely uses reaction shots.) As with Lento’s fall in Colossal Youth, Costa ellides the accident itself and, instead, cuts to a low-angle shot of Mariana, presumably at work, as two hands reach upward and grab her face. Costa reuses the same low-angle shot in his next film, Ossos, again with a patient reaching for a nurse. The image is uncanny and terrifying, like a final, desperate struggle before death wins out.

Any illusions Mariana has about the romantic allure of Cape Verde are challenged from the moment she arrives there. Dropped off in a barren field by helicopter, she finds herself alone with Leao’s still-unconscious body. And when she does finally find her way to the small medical clinic (a former leper colony), she’s frustrated to discover a general apathy about her patient’s condition. Like so much Post-Colonial art, Casa de Lava explores the various ways in which meaning is interpreted and reconstructed by competing powers. The film is full of ambiguities, in the best sense of the word. Mariana is forever asking the Cape Verdeans to speak in Portuguese rather than Creole. “I don’t understand you,” she repeats again and again. When she finds a love letter written to Edith, an elderly colonialist whose pension is a boon to the local economy, Mariana can’t help but misinterpret its significance. (It’s the same letter, by the way, that Ventura recites throughout Colossal Youth.)

“You ate our food. You drank our wine. Maybe it turned your head. Not even the dead rest here. Don’t you hear them?”

And yet Mariana can’t help but be seduced by the Otherness of Cape Verde. The image above captures her at her most deeply enchanted, lost in the music that surrounds her. Except for O Sangue, which features a lush and oddly romantic score, Costa’s films employ very little non-diegetic music. The Hindemith sonata is a notable exception, but it serves as a weighted counterpoint to the diegetic fiddle music played throughout the film. Typically, Costa uses diegetic music to establish a kind of domestic community (as in his many indoor dance scenes) or to invoke nostalgia (see Dave McDougall’s post about “Labanta Braco” in Colossal Youth.) Here, the music is one more seducer that tricks Mariana into believing that she is the object of desire. It’s also one more language that she invariably misinterprets.

Mariana only realizes her mistake — that she has “brought a living man among the dead” — in the film’s closing sequence. Appropriately, the final images in the film resist simple interpretation. Without spoiling the plot, I’ll say only that Mariana witnesses two events that shatter the illusions that had sustained her during her week in Cape Verde: that she was a source of health and healing for the wounded people there, and that she held sexualized power over them. At her moment of awakening, Costa frames Mariana in a still close-up and, for only a few seconds, brings back the non-diegetic viola music. When the music ends, so does her story. Costa concludes Casa de Lava, however, with two last shots that demonstrate what we could maybe call post-colonial inertia. In the first, a band of musicians, all of them men, sets off on one more trip to Portugal, where they are seeking work. (“Everyone wants to leave” is a common refrain throughout the film.) Despite more than three decades of independence, Cape Verde is still inextricably bound to its colonial founders, and the cycle continues. The final shot is more enigmatic. It’s another portrait of the same nameless woman pictured at the top of this post. She returns in a similar role in Ossos, acting as a kind of silent, iconic witness. I think Costa’s ethic is located in that face.