This was originally published in the 2013 Muriels countdown.

– – –

Dir. by Claire Denis

That Claire Denis had made a film noir came as little surprise. Denis is a classic auteur in the sense that, throughout her 25-year career, her visual style and thematic preoccupations have remained remarkably consistent, regardless of subject or genre. She’s made family dramas, music and dance documentaries, a coming-of-age story, a horror tale, and a variety of films that defy simple classification. Adding a noir to that list made sense. However, the pitch darkness of Bastards, its near-total nihilism and its treatment of sexual violence, caught many critics and viewers off guard. Reviews were mixed coming out of Cannes, where it premiered in Un Certain Regard, and even Denis’s strongest advocates (I’d include myself among them) have been slower than usual to fully embrace it. Bastards is indeed a hard film to love. It’s wicked, painful, and soul-sick. It’s also the best new release I saw in 2013.

Bastards opens with a suicide and with a dreamlike image of a young woman walking naked through a vacant Paris street. In her typically elliptical fashion, Denis spends the next 90 minutes piecing together the two events. If there is a single defining characteristic of Denis’s cinema, it’s her subjective camera, and here she adopts the perspective of the suicide’s brother-in-law, Marco Silvestri (Vincent Lindon), a sea captain who abandons his ship to return home and care for his sister and niece. We in the audience know only what Marco knows — that the family’s manufacturing business is in ruins, that his brother-in-law was deeply indebted to local tycoon Edouard Laporte (Michel Subor), and that his niece Justine (Lola Créton) has been hospitalized. The rest is a puzzle to be solved in classic noir style, complete with fistfights, fast cars, and a seductive femme fatale (Raphaëlle Laporte, played by Chiara Mastroianni). Marco is Denis’s rendition of the kind of character Toshiro Mifune played in Akira Kurosawa’s films: battle-tested and honor-bound but still open and exposed. The film is so emotionally brutal because we discover each new horror alongside Marco, as if we’re supporting a grieving friend at the graveside.

I saw Bastards two nights in a row at the Toronto International Film Festival. After the first screening, I was shocked by the bitterness and despair; after the second, I was overwhelmed by the sorrow. It’s an essential distinction, I think. Bastards is Denis’s most Lynchian film: the story echoes Twin Peaks, certain scenes and characters recall Lost Highway, and the style of the film reminds me at times of Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. (Bastards is Denis’s first narrative feature shot on digital, as Inland Empire was for Lynch.) But more than anything else it’s that moral distinction between despair and sorrow that makes this a Lynchian film. Darkness, nihilism, anxiety — these are relatively easy conditions to reproduce on screen. Lynch has an innate and uncanny talent for expressing the transcendent loss that inevitably accompanies violence and human tragedy. That is what Denis taps into here.

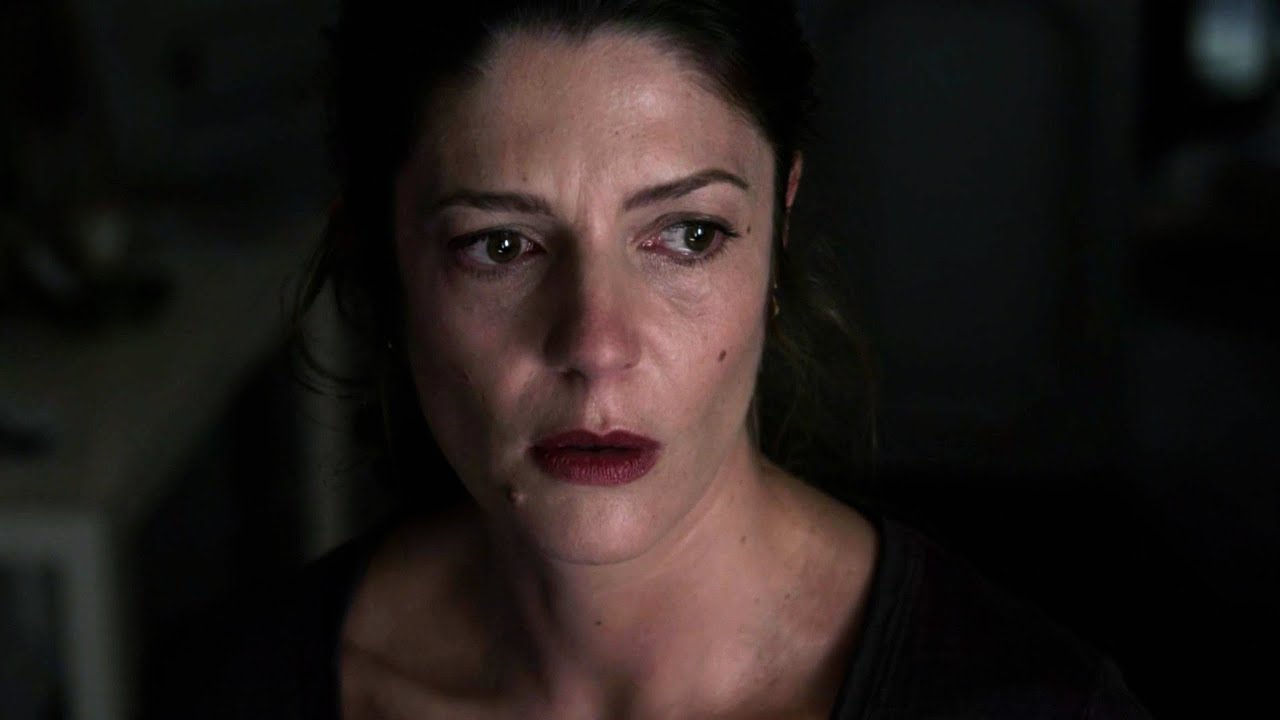

Bastards ends with an ugly image of an ugly act, a father molesting his child. What makes it doubly horrific is that we’ve already seen this image many times before in the film. It’s become familiar, a gestural echo. Denis and cinematographer Agnes Godard are among contemporary cinema’s great portrait artists. They shoot in intimate close-ups that make the actors’ bodies present and familiar. The final image, although desaturated and pixilated, is no exception. At the moment of violence, the father and child embrace and the film cuts to black, which summons retroactively every other embrace in the film: Marco holding Justine in the hospital and his own daughter in his apartment or Laporte taking his young son’s hand as they ride in a limo. Most devastating of all is a moment between Marco and Raphaëlle — he walks through a door, she grabs his jacket by the lapels and pulls it down off of his shoulders, they embrace — that Denis restages at the climax of the film, this time between Raphaëlle and her son. “The first taboo is incest,” Denis told Nick Pinkerton. “It’s the origin of the law.” The sorrow in Bastards is primal, eternal. It’s the poisoning of affection, the blaspheming of love.