Seven or eight years ago, when I was just beginning to explore world cinema, I went through a Godard phase during which I watched most of his early features — Breathless, Les Carabiniers, Contempt, and five of the Anna Karina films. I ended my run with Pierrot le Fou, partly because the later films weren’t then available on DVD but also because Godard’s turn at that point in his career threw me for a loop. It wasn’t the formal complexity of Pierrot that startled me (formally, it isn’t terribly different from the films that preceded it); it was the anger, bitterness, and despair. The final sequence in that film — Belmondo painting his face, wrapping his head in dynamite, lighting the fuse, struggling for a few terrifying seconds to put it out again, and then (after a cut to a long shot) blowing himself to pieces — scared the hell out of me. I wasn’t sure I was ready to follow Godard in this new direction.

Over the last few weeks I’ve watched for the first time the five features that followed Pierrot le Fou, all of them released in 1966 and 1967: Masculin Feminin, Made in U.S.A., 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, La Chinoise, and Weekend. They mark several key transitions in Godard’s career. As his marriage to Karina dissolved, so did their working relationship, and Made in U.S.A. would be their last collaboration. Jean-Pierre Leaud, who’d made uncredited appearances in a few of Godard’s earlier films, stars in four of the five here, the exception being 2 or 3 Things . . . , which Godard filmed concurrently with Made in U.S.A. (one was shot in the morning, the other at night). Godard’s use of Leaud seems to reflect his growing disenchantment with his own generation, who are increasingly represented as grotesque bourgeois decadents (the couple in Weekend, for example) by comparison to the young radicals who were then animating so much political unrest in France and the rest of the world. We see this also in Godard’s use of his new young wife and leading lady, Anne Wiazemsky, whose expressionless face offers a stark contrast to Karina’s glamour, and whose characters are more likely to assassinate government dignitaries or spraypaint Maoist slogans than to sing or dance.

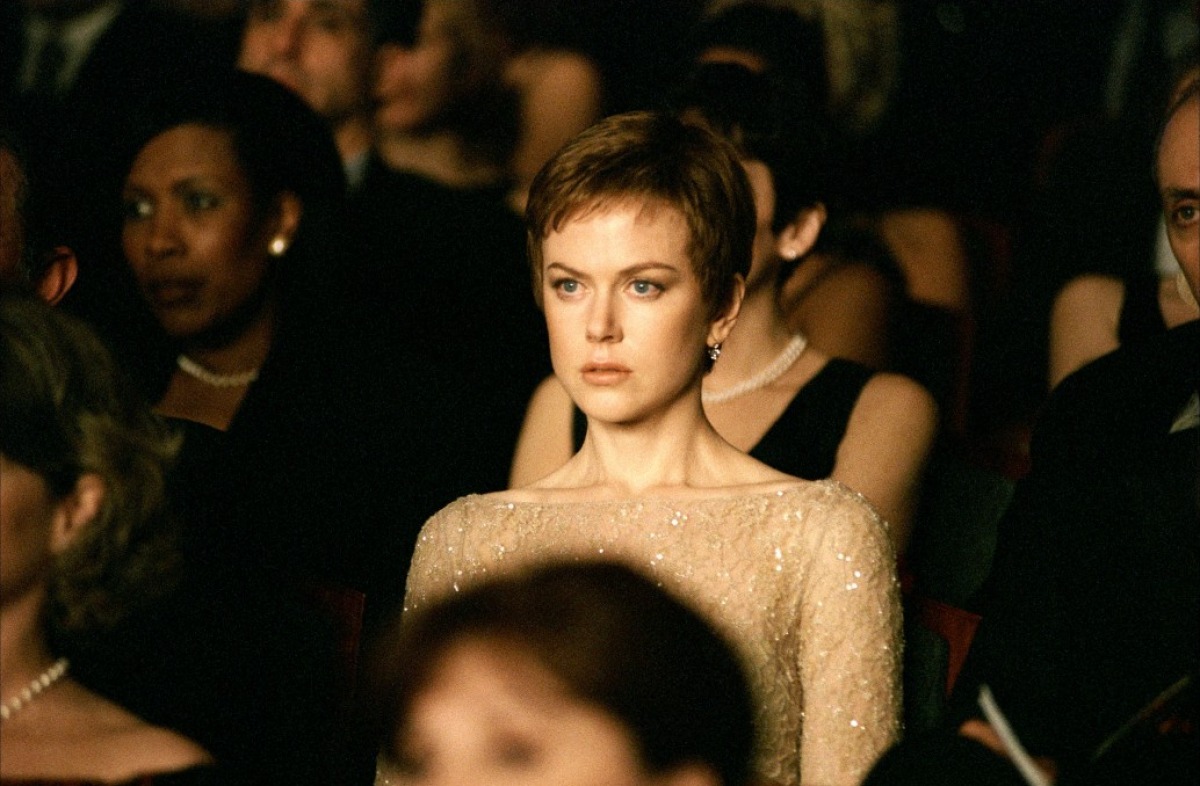

It’s the formal turns, though, that make these films so damn exciting. I happened to have watched Masculin Feminin just a few hours before meeting Caveh Zahedi for dinner last month, and I was surprised when he told me he’d never seen it all the way through. Always the Brechtian, Godard had been using distancing effects and winks to the camera (both literal and metaphoric) since his pre-Breathless days, but the interview segments in Masculin Feminin disregard, once and for all, the documentary/fiction distinction. (They also strike me as the most Caveh-like sequences in any Godard film I’ve seen.) I especially love the long interview with France’s “real” Miss Nineteen, which begins as an innocuous enough conversation before turning to more sensitive and awkward subjects like birth control and reactionary politics. Godard echoes the interview with similar conversations between his “fictional” characters. By La Chinoise, one year later, Godard has dropped the formal artifice completely, including in the final cut his off-camera questions to Leaud, the actor/character — questions about the film itself!

Tearing down the distinctions between documentary and fiction is a key step in Godard’s deliberate move away from genre (the gangsters, singers, soldiers, and sci-fi detectives of his early films) and toward something closer in spirit to an essay. Juliette Jeanson of 2 or 3 Things . . . might call to mind Nana of My Life to Live, but her turn to prostitution isn’t some inevitable concession to narrative convention; it’s an economic transaction. Godard’s growing dissatisfaction with commercial cinema is palpable here. With 2 or 3 Things . . . he is exploring film, instead, as an explicit method of analysis — in this case to study and critique the suburbanization of Paris and the growing middle class. In this context, the apocalyptic violence and decay of Weekend is downright sublime. “End of film. End of cinema.”

I’m less willing at this point to comment on the political content of these films. I still hope to track down a few of the Dziga Vertov Group projects, which, I assume, will help to unravel Godard’s thinking in this regard. That a film like La Chinoise even exists says a great deal about the tenor of the times in which it was made, and I’m eager to give it another viewing. (I watched it last night, so it’s just begun to percolate.) For now, I’m content to allow the sloganeering and the recitations stream right on by and to enjoy, instead, the revolutionary dissonances of Godard’s aesthetic choices (and surely that was his intent): His Mondrian-like use of blue, white, red, and yellow (see image above); the minutes-long tracking and crane shots; the piles of burning wreckage; the urgent absurdity of it all.