This interview was originally published at Filmmaker.

* * *

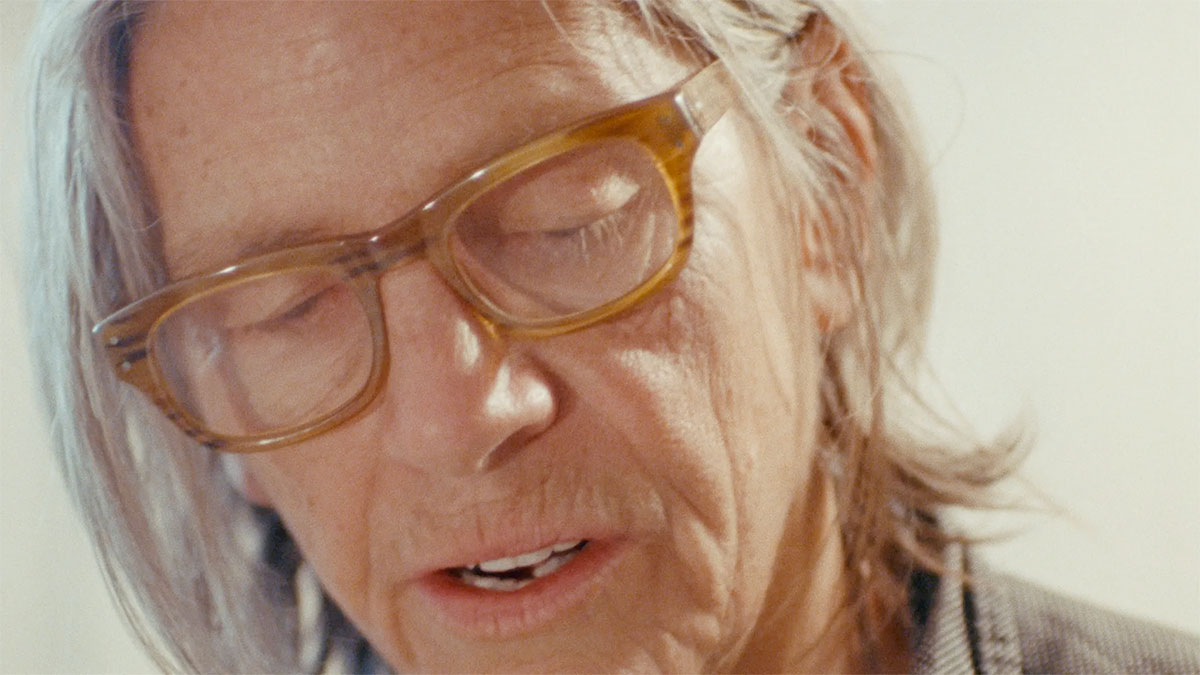

Valérie Massadian makes her first on-screen appearance in Milla near the film’s midpoint. The writer/director/editor plays a small but crucial role as a housekeeper at a remote seaside hotel. We first see her in a wide shot, pushing a cleaning cart down an empty hallway. When the title character, a pregnant teenager with little education and few prospects, takes a job at the hotel, Massadian’s unnamed housekeeper takes the girl under her wing. They make a fascinating study in contrasts. Massadian’s movements are practiced and efficient, honed through decades of labor. Séverine Jonckeere, who plays Milla, is disinterested and inept, a novice.

That I’m referring to the actresses rather than the characters they play is a consequence both of Massadian’s style, which grows out from her inquisitive attention to physical presence, and of the scenario, which draws parallels between the two hotel employees that mirror exactly the parallels between the filmmaker and her ingénue. Milla is a crafted piece of fiction, rounded out by a tragic subplot and elevated by occasional bursts of expressionism, but Massadian’s collaboration with Jonckeere, like her handling of the child actress Kelyna Lecomte in her previous feature, Nana (2011), results in a kind of hybrid viewing experience. Massadian is Jonckeere’s mentor, both in front of the camera and behind it, and that relationship is somehow the essence of the film.

Massadian laughs easily and often in conversation. She’s frank, self-deprecating, and sincere, a disarming combination. I spoke with her on February 2, 2018 at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, where we discussed her path to filmmaking, the problems of observational cinema, and her next project, a dystopian fantasy about a pack of wild children that is “much worse” than Lord of the Flies.

FILMMAKER: English-language press always describes you as having come to filmmaking by way of photography, noting your long association with Nan Goldin, but I don’t know much else about your background. If you’ll forgive such a basic opening question, where did you grow up?

MASSADIAN: Not really anywhere, because I moved all of the time with my parents, from one house to another. The longest we stayed in any one place was about a year-and-a-half, in a destroyed house that we rebuilt and then sold to somebody rich. It was always like this, in the countryside of France, two or three hours from Paris.

When I was 13, I got very tired of this. My parents were often not there. My brother called me “Mama.” It was weird. So I left. I ran away. I went to Paris on my moped. When I got there I started crying like an idiot, because I had no clue what I was doing. I got arrested after four days because my parents were looking for me, and this African woman gave me shelter because she saw me crying. Then we all moved to Paris.

FILMMAKER: The whole family?

MASSADIAN: They were always in Paris and we were left in the middle of nowhere, literally. We lived not in small towns but in the fields and forests. Voilà. From there I did so many jobs. I started working very early on. I did every kind of job that anyone who has no education can do. There’s a saying, “Curiosity is a bad thing.” But I’m part Armenian, and in Armenian it’s the opposite. I really have that. So because I’m curious I started reading and going to the cinematheque.

FILMMAKER: At what age?

MASSADIAN: Very young. Like 14. I was always sneaking in the back door. Always. Because I needed . . . I was hungry. Then I was in Japan, modeling. It was a complete mistake but also it was great. I did it for two months and was loaded with money, which allowed me to live in New York for two years. Then I came back. I worked with Nan Goldin.

FILMMAKER: How did you meet Goldin?

MASSADIAN: I was designing clothes with Jean Colonna, and one day she came. I received an email asking if she could come to the atelier. She was doing a piece for The New York Times Magazine, following James King, and I was doing the casting. So she came. That was the beginning of a long friendship.

FILMMAKER: Was modeling your entree into the fashion job?

MASSADIAN: Not at all. It was only in Japan, and then I went to the States. I repaired bikes, I wrote copy, I did other things. No, no, I got into fashion because I was pregnant up to my teeth and a friend of mine was doing paperwork for this guy who was working for Colonna. One day I went to pick her up and she wasn’t there but he was. I was stupid, this punk kid, but I guess it was a good kind of dumb.

FILMMAKER: What do you mean by that? You keep describing the younger version of yourself as stupid.

MASSADIAN: I refused to compromise but I did it in a stupid way. I could be very aggressive. I was vehement because I was a kid.

I didn’t know what to say to him, and we were sitting like this, and I said, “I heard you want to do a fashion line.” He said he did. So I said, “Well, don’t you have to do fashion shows and things like that?” He said, “Yes, but for that you need money.” I said, “Well, money you can always find.” He said, “If you’re so smart, you do it!”

At the time I had a job at Pyramide, the film distributor, which Fabienne [Vonier] was just starting. She took me because I was super honest and I was pregnant. She also had a child when she was nineteen — I learned this a long time after — but she couldn’t take care of the child, so she gave it to her parents. She was very touched and impressed that I was going to take care of my child. I also knew quite a lot about films and loved cinema. I was working there and, at nights, had a dossier to go look for money for Jean. And we found it. We got, like, 60,000 francs from the Ministère de la Culture and another 30,000 from a cigarette sponsor and Absolut Vodka gave us I forget what.

It started like this. And then we did the first show and he said, “Well now what are you going to do?” And I said, “I have to find a real job because I can live in a small space but my child is not going to.” He said, “What if I manage to give you 5,000 francs in cash.” I thought, “5,000 cash, 3,000 welfare, that’s 8,000. Yeah, I’ll stay.” And we worked together for ten years. He’s the first person who trusted me for who I was — this pain-in-the-ass animal, violent, big-mouthed whatever that I was. That’s huge in someone’s life.

I didn’t care about fashion. I mean I loved making clothes, but for me they’re clothes and you don’t change clothes every season. I think fashion is kind of disgusting. But I like making clothes for my friends.

FILMMAKER: You left Colonna to work with Golding?

MASSADIAN: I needed to learn. From when I was very small, it’s never left me, this . . . anger?

FILMMAKER: Hunger?

MASSADIAN: Yes, hunger. Anger, too, but that’s another thing! When I get to a point where I’m not challenged, I’m not learning, it makes me very nervous. I hate it. I have to find something to improve myself. I was doing a lot of other things at Colonna — we shot short films, we worked with artists, we did tons of things — and it was an incredible space of freedom. But then, because it’s also a very capitalistic business, if you don’t make a lot of money you have to sell out. I said, “I’m out,” because I didn’t feel clean.

I always wanted to make films but that also requires money. Taking pictures became my relation to the world and my way to connect with it. But that you can do alone. You put a camera in your bag. Film is a different story.

FILMMAKER: Your filmography includes a couple years when you did a variety of jobs on a variety of films.

MASSADIAN: I designed a collection for some people and asked them to pay me cash. They were very happy, and that money was my film school, basically. I made a short film downstairs from my house in a bar with some crazy men. I never finished it, but every mistake you can make, every drama that can happen, it all happened. That was perfect.

I did two films with François Rotger (The Passenger, 2005, and Story of Jen, 2008) and then Michelange Quay (Eat, for This is My Body, 2007). With them I did everything, from location scouting to working with actors to set design. They were small budgets but much bigger than my budget.

And then, I got tired because I thought they were lazy. And I said, “If I can give this [effort] to them, then I can give it to myself, and I should.” Also my son was older, so it was my turn.

FILMMAKER: How old is he now?

MASSADIAN: Mel’s the DP of my film. He’s 26. Only nineteen years separate us. He really has an eye, and he has his own thing. I respect it a lot. We once filmed my mother for a project and she suddenly burst out laughing. She said, “You have no idea. It’s like a Buster Keaton film. You do not talk. You look at each other and nod. He changes the lens. It’s like a silent film.” So when I wanted to make Milla, I said, “You have to think. Maybe it’s more difficult for you to detach from the fact I’m your mother. I want you to do it because I love the way you work. The way you frame is the same way I frame. You have the same relation to space.”

FILMMAKER: Does he have any traditional training in film production?

MASSADIAN: No, Mel started being on the computer and making me nervous when he was 11. I’d say, “enough,” and he’d say, “But Mom you don’t know what I’m doing. Let me show you.” And then I’d see this 3-D animated character. He had cracked software and it was super complicated. He’d learned from blogs. That online community is completely different from cinema. It’s very together. At 11, he was talking to professionals in America, learning how to work with light and where to place the camera.

A friend helped me find him an internship and I said, “Okay, we’ll make a deal because you’re really young. You have to finish school and not be as stupid as I am. It’s just paper. It’s completely ridiculous. But in ten years if you want to be a veterinarian, you won’t be able to go if you don’t have this stupid paper. Get that paper.” Then he wanted to learn real lighting, so he did an internship with a photographer. He’s really good. He has a do-it-yourself attitude.

FILMMAKER: I can see where he gets it.

MASSADIAN: Yes!

FILMMAKER: Along with Nana and Milla, you’ve also made a couple short films. What is your professional life like right now? Are you constantly making work?

MASSADIAN: Yeah, because I have to live. I made a trailer for a friend because the film is very particular and everybody proposed ideas that were completely horrible. So, I do that or I make posters or I work with friends. Now, it’s nicer. I used to feel really guilty when I wasn’t doing anything. Guilt I don’t have so much in my life but when I wasn’t doing anything I felt it. Now I’m starting to learn that I can also lay back and read a book.

FILMMAKER: Thanks for indulging me. I wanted to begin the conversation like this because when you first appeared on-screen in Milla, I knew immediately that you were at home in the world of hard work. That wasn’t the first time you’d ironed clothes.

MASSADIAN: No, no, no. And I would also look in suitcases! It’s so strange to keep walking into intimate spaces. You walk in and there’s pants and socks and knickers on the floor. It’s a very strange position.

FILMMAKER: I thought about that this morning when I woke up in my hotel! I very neatly laid out my clothes before leaving.

MASSADIAN: Of course.

FILMMAKER: Last night during the Q&A, you said that when you were developing Milla you wrote a script for the financiers but then threw it away. What did the script look like?

MASSADIAN: There was no boy. It was only her. She was running away from the projects and she landed at this hotel by the ocean, run by an older woman. It was one of those hotels lost in the middle of nowhere, where truck drivers stop for one night, or salesmen, mostly men. Both characters were very closed and tough — there are parallels here — and this woman decides to take her and make her do her studies. It was two solitudes, that were different because of age and time in life, but they resonate. And basically they both opened up. The script was very tender. But then I met Luc [Chessel]. And voilà it went somewhere else.

FILMMAKER: Did you always intend to play the older character?

MASSADIAN: I had a woman but she wouldn’t commit because I’m slow. We take a lot of time. And also Séverine was really rough because she was scared. Suddenly someone came into her life and said, “I care. You’re beautiful. And I’m going to show you that you are worth something.” For Séverine it was dangerous, because it meant she could get attached, and from her background to feel attached is to feel pain and betrayal. So her reaction was to be very violent.

The first thing we did was the scene when I’m ironing and there are cookies. What I say to her — “You’re short and pregnant but you’re not crippled” — that’s the way I talk. And she knows. So she said, “Oh, you just want me to be with you?” I said, “Yeah, be with me. Or be with Luc. Or be with your son. That’s all. I don’t want you to do anything. That’s my job.” It shifted everything. Suddenly she could find pleasure in being there and opening a little bit, little bit, little bit.

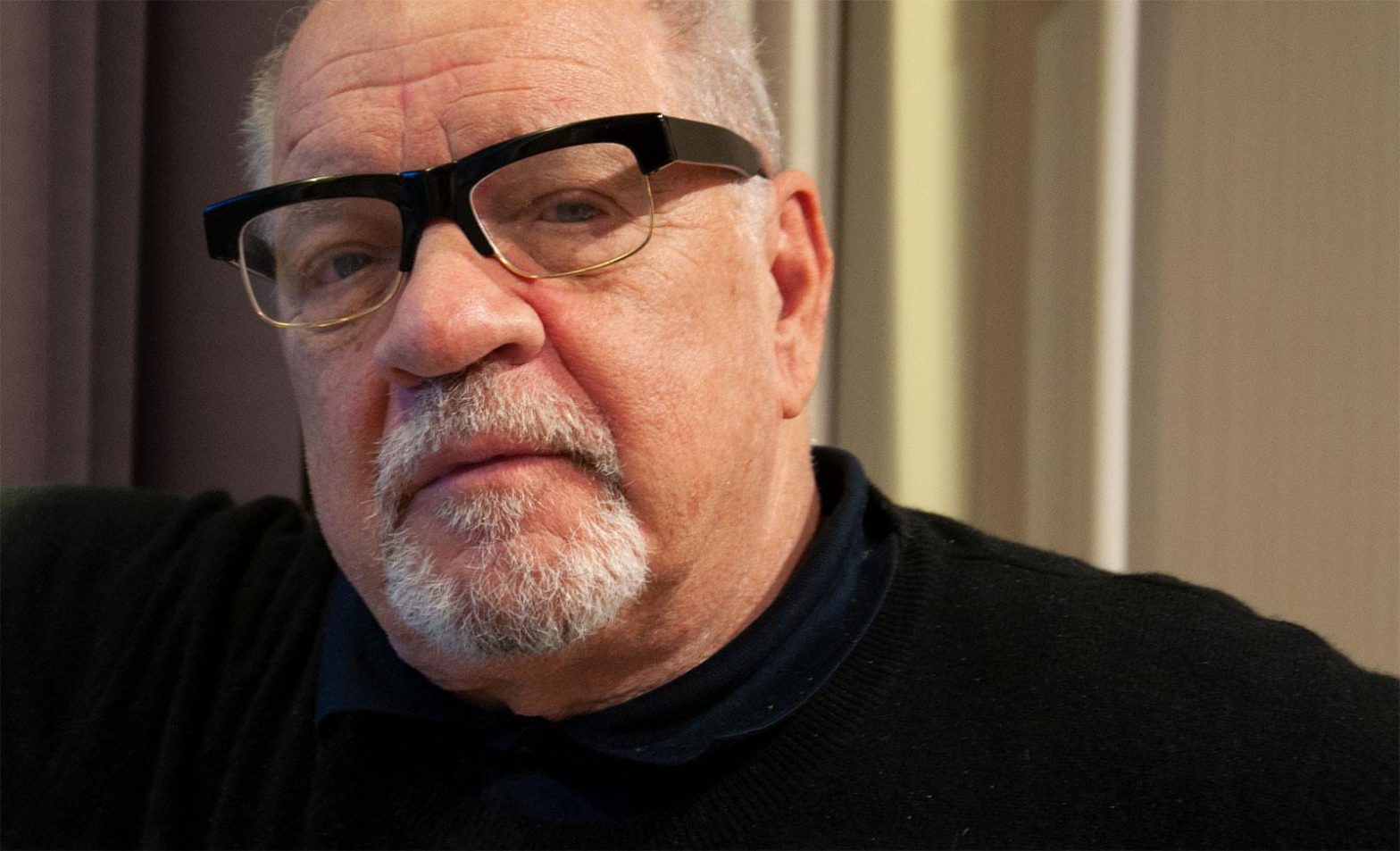

FILMMAKER: I was happy to see Luc. I only know him from Low Life (Nicolas Klotz, 2011).

MASSADIAN: Yes. Luc is very interesting. I knew his face from Low Life and from Atomic Age (Héléna Klotz, 2012). He always had small parts, but his face burns the camera. Just incredible. Luc also writes on cinema for Libération, but I didn’t know it was the same person. I remember the first thing I read by him. It was obvious he didn’t like the film politically and cinematographically, but he was talking to the filmmaker. I read the thing and I remember saying, “Man, if this was my film, I’d want to meet this guy.” The way he writes, and how respectful it is of the work and the person, is so rare. Then I met Luc at a party. We started talking. To me, he was this young kid [the actor], and then we started arguing about a film and I said, “It’s like this guy, I can’t remember his name, but he wrote this big text on a João Pedro Rodrigues film, and na na na.” I’m really pissed off because we’re arguing for real, and I say, “What are you laughing about?” And he says, “I’m the one who wrote this.” Suddenly the two became one. I thought to put [Luc and Séverine] together would help. And it did.

FILMMAKER: Adding Luc’s character must have transformed the style of the film too, right? It moves the story into a more poetic and tragic realm.

MASSADIAN: In France we had month-long demonstrations with the young, with kids, against the government labor laws. Those kids were between 16 and 24. They were, of course, represented by the media as idiots out to destroy. I went to a lot of the demonstrations. You have 17-year-old kids who do not come from a bourgeois, educated social class, and it had that romantic feeling I hadn’t felt for a really long time. They were fascinating. These kids really don’t want this world and are very articulate about it. So to have this couple of misfits, that’s where the love story came. And then because I wanted her to be the main character …

FILMMAKER: You had to kill him off.

MASSADIAN: Yes! And I didn’t want him to leave. Some girls say, “He’s a little rough with her and abusive,” and I say, “He’s not.” First, he’s the only one who says, “I’m afraid.” I don’t know a lot of men who say “I’m afraid.” They’re both teasing each other. It’s almost a seduction, a sexual game, when you’re that age.

FILMMAKER: His character also gave you an opportunity to film another kind of hard work.

MASSADIAN: Yes, I met the fishermen. At first they said, “Please, this girl.” But I kept returning every night at 6:00 when they were leaving, and finally they said, “Fine, you can come with us.” So I went and I filmed all night. I worked. And they were working. In the morning, when we came back, they were, like, “Okay, you’re not a wanker. You worked. So you can come back.” I said, “Can I come back with an actor?”

It’s constant writing until the end of the editing. The script? It was for the people who gave us money. Or loaned us money. On Nana, they said, “It’s not the script but it’s the film.” On this one they said, “It’s still not the script. It’s actually better than the script.”

FILMMAKER: Milla is in a slow, observational style that has become common at festivals like this over the past decade. I’ve seen a lot of them, as I’m sure you have, and many of them feel inert, like there’s no one behind the camera. You said last night during the Q&A that you have to watch an image 150 times before you can be sure it has life in it. I wonder what the difference is?

MASSADIAN: To me, it’s all in this word “observational.” I’m not observing, because that’s a position. The only judgment I will have on a film is political: the position of the person filming. What is your position? And this “observational blah blah” is very arrogant. For me it’s worse than that because …

FILMMAKER: It’s exploitative.

MASSADIAN: Yeah. It’s like anthropologie. It already has a superiority, like, “I’m going to watch.” I love Jean Rouch for that. He’s not observing. Then you take Robert Gardner and he’s very observing. For me, it’s beautiful work, it’s incredible that they went to these places. I cannot stand the films. To me, it’s violent because it’s objectifying people. It is the majority [of films being made], and it’s a matter of position.

Sometimes people say, “It’s a little corny when you talk about how you love and care [for your collaborators].” Well, fuck you. I’m corny. Seriously. Ten years from now, I can look at myself in the mirror and I’m fine, you know? I cared and I was protecting people. Even when you pay an actor, still it’s a person. This “observing” makes me really mad. People don’t realize how politically disgusting it is. In documentary it’s even worse.

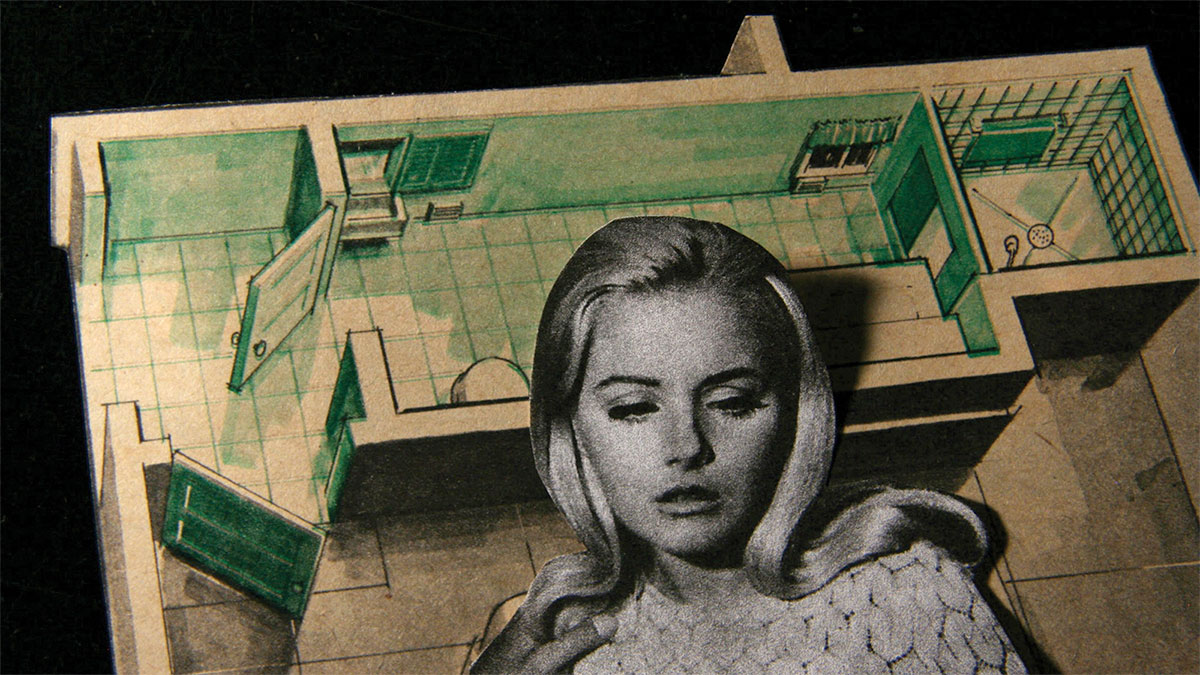

FILMMAKER: I’d like to talk about the scene in Milla when she visits your character’s bedroom. We mostly watch her eyes as she looks around and explores your space. The camera stays very close to her. I think it’s on a tripod?

MASSADIAN: Yes, yes. The camera doesn’t move much, but it does here.

FILMMAKER: I’m curious about your shot-making process. How did this scene come to be?

MASSADIAN: This I had written in the script. I wanted, through this sequence, to go through my character’s life. You don’t know anything. She’s just there [at the hotel]. You understand very fast that there is a parallel between the two; she’s the same but older.

I wanted Milla, through objects, to draw the life of this woman. There’s a bridal item from the 19th century, there’s the music box, and there’s the picture, and you suddenly realize she also had a child when she was very young. The camera had to be very close to her because … now that I have to think about why … [long pause] … if you’re not as close it becomes intrusive, like she’s intruding on this woman’s life. But when you’re with her, it’s sensual. She’s not sneaking. She’s very gently and shyly traveling and discovering, like Alice in Wonderland.

FILMMAKER: Did Séverine have freedom to move or did you block it?

MASSADIAN: We dance. I tell her the objects, so she goes from here to here. This we didn’t even rehearse. We did five takes, which is a lot for me.

FILMMAKER: I have a friend whose response to Milla was, “This woman knows how to direct goddamn curtains.”

MASSADIAN: Thank her! [long laugh] Tell her I love her.

FILMMAKER: The film has a number of images that are staged and decorated, in the sense that they’re like portraits. I’m thinking of Milla posed in front of the hanging sheet outside or when she’s petting the cat by the curtain. It’s like you’re telling the audience, “We’re going to take a few seconds to just sit with Milla in this beautiful image.” What function does that play in developing the character or shaping your viewer’s experience?

MASSADIAN: I only give them actions and objects, so I also have to give them space. I don’t care if they go out of it, but they know the space. It might sound strange, but in a way I’m putting people, objects, and spaces at the same level. Of course, the care I feel for a person is very different than a plastic cup. This is why I say I drain the shit out of watching the shots. If there’s something in the shot, if it stays alive, it’s everything — from the curtain that goes like this [Massadian waves her hand] to suddenly, just before the end, the cat walks out. Everything.

I’ve always been fascinated by how, in a lot of cinema before the 1960s, you would not really see the extras. But if your eye or your subconscious saw them, their bodies, the way they moved, the way they were dressed was all perfect. Now, I burst out laughing when I watch extras.

I believe in the still shot and I believe in the person watching it. For example, the cat sequence: whether you focus on the cat or you focus on Séverine or you focus on the red curtain that moves, it all has to work. And [where you focus your attention] won’t change what you’re seeing or what you’re supposed to feel. Everything in a shot counts. Maybe one person in five or ten will notice there are girl toys and boy toys. When they eat together, there is a pink glass and a blue glass. This kid is only two-and-a-half, and already he doesn’t want the pink glass. A lot of people don’t see that, and it’s fine. For me, everything that is in this shot has to carry something.

FILMMAKER: People don’t have to literally see it for it to matter.

MASSADIAN: It doesn’t matter. That’s why I was talking about the extras. You might not see it, but you do. It’s there. Even if you didn’t notice. That’s what an image is. It should be full, even if it’s very empty.

FILMMAKER: Another practical question. You mentioned that the scene with Luc and Séverine counting coins was assembled from a 28-minute take. When you took a first look at that take, did you find, say, a three-minute section that had potential and then throw it into another folder? And then maybe, when you returned later, those three minutes became 70 seconds in the film?

MASSADIAN: Yes. It’s strange. This guy said, “Oh, when you edit you just put an ‘in’ and an ‘out.’” Just? Because the sequence has been edited, you feel it begins here and ends there, and there’s this movement through three layers of emotion.

In the sequence with the books, I gave Luc a book on slang of the fishermen — it’s like a dictionary — and he’s reading the words that are sexually ambiguous and really funny. And then there’s Duras, and then they talk about sex, and then lying, and he doesn’t care about lying and she has a problem with it — I mean, this is a gift of the gods.

FILMMAKER: There’s some real hostility in her delivery of those lines.

MASSADIAN: Yes, and she didn’t even realize it, because it went completely somewhere else. But I knew, so I walk in and change the scene. The camera doesn’t even cut. We will create four or five different possibilities but the result is always similar.

FILMMAKER: How did making the film affect Séverine?

MASSADIAN: She says it better than I do. When I was editing, I was fighting with her all the time because she was ashamed to be on welfare. She took a shitty job in a restaurant. And I said, “You’re working like an idiot. You do not see your child because you work. The money you make, you spend to pay the babysitter. Can you please explain? You want to go to school? I’ll pay for the fucking school. But I’m not going to help if you fuck up like this because it’s ridiculous. You’re not thinking straight. I could understand if you were on welfare and you were sitting like a fat cow on your couch watching television and eating chips or getting drunk. That’s not the point. See it as the government paying for your education. Get your exam.” She wants to be an educator. Because Harvard gave me a fellowship, I was so rich I could send her money.

That went on for a year-and-a-half. And then she came to Locarno, she saw the film, and she basically said, “This really changed my life because now I see that I’m not so worthless. I think it’s even going to change the relation with my son because Valérie made me so patient in the film.” Three days later she went back and sent me a picture of her resignation letter. She started working on her exam and would send me photos of her scores.

She got her driver’s license. She’d been in a toxic relationship with an idiot. She realized all of this. And also she learned to trust a little bit. She trusts me. I’m like an aunt or something.

FILMMAKER: You’ve said that you want to make a trilogy of films, beginning with Nana and ending with Milla. Do you still plan to make the one in the middle?

MASSADIAN: Yes, but it’s going to take a while because I want to work with 11- to 13-year-olds. This world [of the film] has gone all the way with absurdity and violence, and the only ones resisting were the adolescents, so they’ve all been hunted and put in camps. They’re the enemy. All of this you won’t see. You’ll understand from their stories. Eventually, they will end up in this abandoned castle in the middle of the forest, where there is a huge library and some art — that’s all there is. And they’re going to write a new constitution.

FILMMAKER: The kids are?

MASSADIAN: The kids. But it’s not Lord of the Flies.

FILMMAKER: Good.

MASSADIAN: It’s much worse! Basically, the idea is to take four or five kids. Each will have their own particular interest. One girl is going to learn about plants and medicine, so she’s going to be the doctor. This one, she builds things; it’s all crooked but at least it’s built. This one is a poet.

I said, “Sometimes you’ll go scavenging, like in the zombie movies, and one day you find this woman. She’s 30, super nice, super beautiful, but she’s very sick. What do you do?” They say, “We help her. We cure her.” I said, “Yeah, but then she’s fine and she’s an adult. So there are three possibilities. Either you forbid her to leave; you jail her. Or you let her go but you take the risk that she’s going to bring back others and you’re in danger; you might even die. Or what?” And they’re like, “Oh, we kill her.” [long laugh]